On the morning of June 2, 2018, an asteroid was seen careening toward us at 38,000 miles per hour. It was going to impact Earth, and there was nothing anyone could do to stop it. Astronomers were beside themselves with excitement.

Five feet long and weighing about the same as an adult African elephant, this space rock posed no threat. But the early detection of this asteroid, only the second to be spotted in space before hitting land, was a good test of our ability to spot larger, more dangerous asteroids. Moreover, it afforded scientists the chance to study the asteroid before its obliteration, quickly narrow down the impact site and obtain some of the most pristine, least weathered meteorite samples around.

Later that day, a fireball almost as bright as the sun illuminated Botswana’s darkened sky before exploding 17 miles above ground with the force of 200 tons of TNT. Fragments fell like extraterrestrial buckshot into a national park larger than the Netherlands.

Immediately, Botswanan scientists and guides joined with international meteorite experts to hunt for the asteroid’s wreckage. As of November 2020, the team has found 24 individual meteorites. And thanks to the telltale geology of these rocky leftovers, observations of their path to Earth and the memories of a dead NASA spacecraft, scientists were able to unspool the history of this asteroid with breathtaking detail.

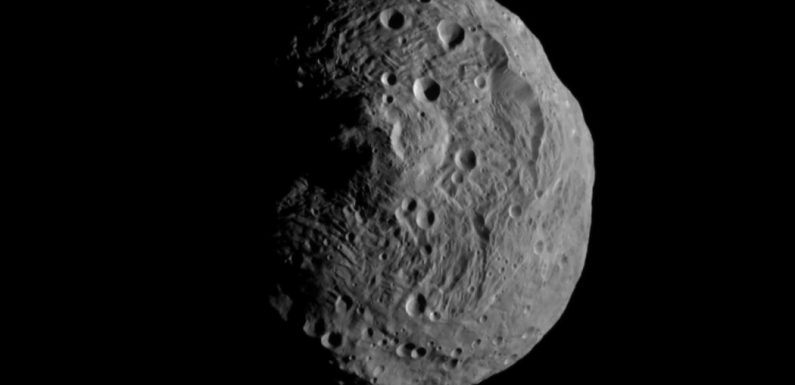

As reported earlier this month in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, Botswana’s off-world visitor was once part of Vesta, a gigantic ramshackle asteroid forged at the dawn of the solar system. About 22 million years ago, another asteroid crashed into one of its lonely hills, leaving a modest crater and sending countless shards of Vesta on a space odyssey. One of them was the object that fell over southern Africa in 2018, an explosive end to a lonely journey.

“It is such an amazing thing to be in possession of such a rare specimen with so much history attached to it,” said Mohutsiwa Gabadirwe, a geologist and curator at the Botswana Geoscience Institute who is a co-author.

Named 2018 LA, the asteroid was first seen by the Catalina Sky Survey, a trio of telescopes north of Tucson, Ariz. Additional telescopes, like the SkyMapper Southern Sky Survey, saw it too, allowing scientists to tentatively map out an impact site in southern Africa.

Peter Jenniskens, a meteorite expert at the SETI Institute and study author, said that the initial search area was a 1,400-square-mile patch in Botswana. Hoping to shrink it down, he visited local businesses with Oliver Moses of the Okavango Research Institute. They located security camera footage at a hotel and gas stations that had recorded the fireball, allowing them to more precisely pinpoint the fall site: a (still-sizable) spot within the Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

This was a surreal place to go meteorite hunting. Bat-eared foxes and warthogs strolled past, lions stealthily stalked and slaughtered giraffes while leopards lounged in trees. Wardens from Botswana’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks protected the search party in case a fanged predator got too close for comfort. The meteorites also looked a lot like animal poop, meaning the team were frequently bamboozled by coprological impostors.

“It was a totally unusual experience for all of us,” said Mr. Gabadirwe.

Only on June 23, the last day of the initial search mission, was the first meteorite found — a small piece of the stars weighing less than an ounce. It was named Motopi Pan, after a local watering hole. “It became a national treasure of Botswana, this little rock,” Dr. Jenniskens said.

The meteorites’ compositions were matched to those found on Vesta, with the help of data from NASA’s Dawn spacecraft. Now lifelessly orbiting the dwarf planet Ceres after running out of fuel in late 2018, Dawn documented the geology of Vesta from 2011 to 2012. Scientists corroborated this origin story by reverse engineering the asteroid’s Earthbound trajectory.

Cosmic rays imprint traces on asteroids by altering atomic nuclei. The traces on these meteorites suggested the asteroid that crashed into Earth bathed in this radiation for 22 million years as it traveled to Earth. That meant an impact crater 22 million years old would mark the spot where this asteroid was liberated from Vesta.

A six-mile-long crater named Rubria on Vesta was the best candidate. The asteroid’s surprising lack of contamination by the solar wind — the stream of plasma and particles coming from the sun — suggested the asteroid’s material was shielded from space for billions of years. Unlike one other similarly aged crater, Rubria sat on a hill undisturbed by landslides, a tranquil place 2018 LA could remain buried before an impact set it free.

“The study has it all, in terms of cosmic drama,” said Katherine Joy, a meteorite expert at the University of Manchester in England not involved with the work. But linking 2018 LA to a specific place on Vesta relies on many underlying assumptions, so no one can be sure that Rubria is the correct spot.

For now, scientists will continue to monitor the skies and scout Earth’s deserts, hoping to find more enlightening fragments of our cosmic cradle’s past. Meteorite hunts “are always incredible adventures,” said Dr. Jenniskens — an exhausting but thrilling way to spend a lifetime.

Source: Read Full Article