Shackleton's ship 'Endurance' found off the coast of Antarctica

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

The discovery of one of the greatest ever undiscovered shipwrecks sent shockwaves across the archaeology world this week. The Endurance, the lost vessel of legendary Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, was discovered at the bottom of the Weddell Sea some 107 years after it sank. It was destroyed by sea ice and plunged to the sea floor in 1915, forcing Shackleton and his crew to flee on foot and in small boats. Video footage shows the ship is still sitting upright on the seabed at a depth of 3,008m, and is remarkably preserved.

While wrecks such as the Endurance continue to amaze archaeologists and historians alike, one of the biggest mysteries in British seafaring history remains largely forgotten.

Hundreds of ships have met their fate off the North Wales coast, particularly off Anglesey, and two stand out in terms of loss of life.

One — the Royal Charter — was recorded by Charles Dickens and later celebrated in song, while the other dates back to around 1,000 years, but a third continues to be largely overlooked.

Gareth Cowell, a Maritime historian, has spent years researching the lost wreck of the 1625 disaster, and his research may finally provide the basis to tell the tragic story.

No memorials were raised and no churches recorded the disaster, meaning that the names and the lives of those onboard were lost to time.

Mr Cowell told North Wales Live last year: “Perhaps the loss of life was so great, and the embarrassment so acute, that no one wanted to acknowledge it.”

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, anti-Catholicism was rife in the Irish province of Ulster, with frequent rebellions and a regular need for military support.

AH Dodd, a historian from Bangor, estimated in his book ‘Studies in Stuart Wales’ that around 1,000 troops were dispatched to Ireland each year in the 1620s.

A consignment of British troops set sail in late winter of 1625 to deal with yet another uprising.

Some 550 soldiers boarded at Liverpool on six merchant ships on March 29, 1625, with sailing crews taking the headcount to 770.

Richard Rose, Mayor of Liverpool at the time, said the weather was “faire at south west” upon their departure.

However, he confessed that the wind had changed direction to a northeasterly that same night and there “arose such a tempestuous storm” as the ships passed Anglesey.

Unfortunately, the ships were no match for the mighty winds and crashing waves.

Mr Cowell’s research revealed how the ships were blown with unstoppable force towards the limestone beach blocks by Penmon Point and Puffin Island.

Only one of the six vessels survived, with 112 on board.

DON’T MISS:

Archaeologists stunned by Solent shipwreck: ‘Takes your breath away’ [QUOTES]

Ancient Egypt discovery took researchers by surprise [INSIGHT]

Ancient Egypt breakthrough as body could explain mummification origins [DISCOVERY]

Of the five vessels lost, 80 men made it to shore from one ship, and eight from another, but the remaining 470 men all lost their lives.

The sole surviving ship reached Beaumaris, which was the main port in North Wales throughout the Stuart period.

Four days after the devastating storm, the “clarke of the company of that shippe” returned to Liverpool, and the city’s mayor wrote an urgent letter describing the enormous losses to the Lords of the Admiralty.

A second letter written by nobleman William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, said the few survivors were “sorely brused” and “struglinge for the preservation of theire lyves”.

Mr Cowell discovered the letter, one of just two known records of the disaster, at the National Archive in Kew.

He said: “It appears the survivors may have run riot in Beaumaris. They were probably freezing and starving, yet no one wanted to have anything to do with them.”

Church records offer no insight into the dead, and Mr Cowell could not find any evidence of burials. He added: “It’s hard to imagine some weren’t washed ashore.”

The mystery of the 1625 disaster runs in stark contrast to the Royal Charter.

Also a victim of northeasterly winds, it is often labelled Wales’ worst maritime disaster, with some 450 people losing their lives.

A memorial was erected in Moelfre, and more than 140 of the dead were buried at nearby St Gallgo’s church.

Charles Dickens was dispatched to Anglesey to report on the disaster, and later wrote about it in The Uncommercial Traveller.

Quite why the Royal Charter was remembered but the fleet heading for Ireland was not remains a mystery. Mr Cowell said: “No one really knows. However the Royal Charter sinking is more recent and its story is more colourful.”

The Dickensian ship was carrying a large amount of gold, and had women and children, with no survivors.

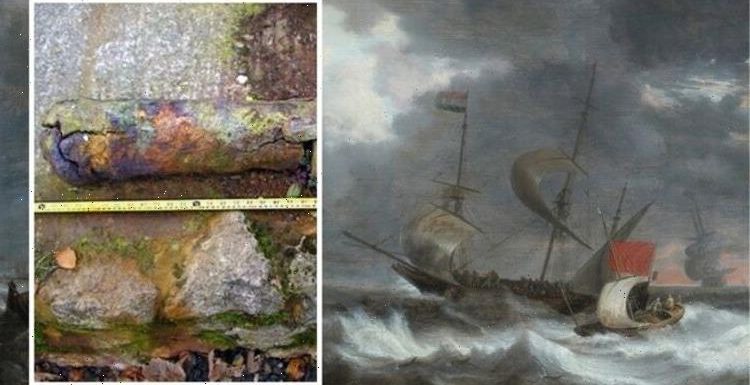

The only physical evidence of the Penmon disaster is the two culverin guns discovered on the limestone seabed by freelance diver David McCreadie in 1995.

Only one was raised, and housed at the National Museum in Cardiff after it was cleaned and reassembled. Mr Cowell remains “almost certain” that there are “many more artefacts on the seabed”.

Source: Read Full Article