Meet Earth’s first GIANT! Huge reptile with a 6.5ft skull, a 56ft-long body and a weight of 40 TONNES roamed the ocean of what is now Nevada 246 million years ago

- ‘Cymbospondylus youngorum’ may have been Earth’s first giant creature

- It was unearthed in the Augusta Mountains of Nevada from 1998–2011

- C. youngorum was an ichythosaur — a highly successful group of marine reptiles

- Analysis suggests this group evolved to such vast sizes in just 3 million years

A giant reptile with a 56-feet-long body that weighed in at a whopping 40 tonnes prowled the ocean of what is now Nevada some 246 million years ago.

The creature — ‘Cymbospondylus youngorum’ — may have been Earth’s first giant creature, palaeontologists led from the Universities of Bonn have reported.

The fossil was extracted from a layer of Middle Triassic-aged rocks known as the Fossil Hill Member that outcrops in the remote Augusta Mountains.

C. youngorum is an example of an ichthyosaur, a highly-successful group of marine reptiles that first swam Earth’s oceans between 250–90 million years ago.

Based on the age of the newly-identified species, it appears that ichthyosaurs evolved to such a vast size in just 3 million years — far faster than whales did.

In one of life’s little coincidences, the reptile’s species name honours Tom and Bonda Young, owners of the Great Basin Brewery of Reno.

And one of their popular brews is ‘Icky beer’ — which happens to feature an ichthyosaur on its label.

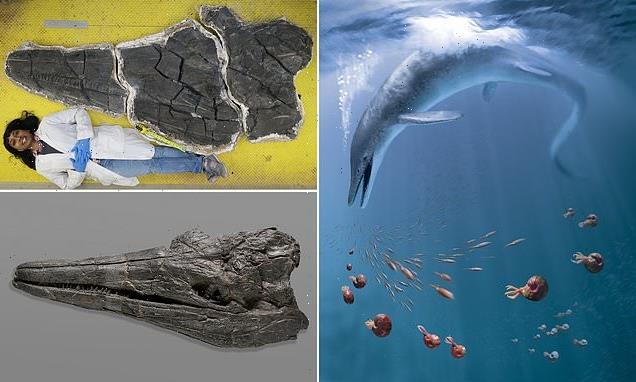

A giant reptile with a 56-feet-long body that weighed in at a whopping 40 tonnes prowled the ocean of what is now Nevada some 250 million years ago. Pictured: an artist’s impression of Cymbospondylus youngorum, along with some ammonites and belemnites

The creature — ‘Cymbospondylus youngorum’ — was Earth’s first giant creature, palaeontologists led from the Universities of Bonn have reported. Pictured: C. youngorum’s skill alone was a whopping 6.6 feet (2 metres) long

C. YOUNGORUM STATS

Order: Ichthyosauria

Age: 246 million years ago

Locality: Augusta Mountains, Nevada

Length: 56 feet (17 metres) long

Weight: 40 tonnes

Head size: 6.6 feet (2 metres) long

The study was undertaken by vertebrate palaeontologist Martin Sander of the University of Bonn and his colleagues.

‘From the first skeleton discoveries in southern England and Germany over 250 years ago, these “fish-saurians” were among the first large fossil reptiles known to science, long before the dinosaurs,’ Professor Sander said.

‘They have captured the popular imagination ever since,’ he added.

Fossil remains of C. youngorum were first unearthed in the Augusta Mountains back in 1998 — specifically in the form of fragments of the creature’s spine.

‘The importance of the find was not immediately apparent, because only a few vertebrae were exposed on the side of the canyon,’ said Professor Sander.

‘However, the anatomy of the vertebrae suggested that the front end of the animal might still be hidden in the rocks,’ he added.

It wasn’t until the September of 2011, however, that the researchers proved this notion correct — excavating out of the rock a well-preserved (and 6.6-feet-long) fossil skull, forelimbs and chest bones from the large ichthyosaur.

According to Professor Sander, the marine reptile was certainly the largest animal ever discovered from this time period.

‘As far as we know, it was even the first giant creature to ever inhabit the Earth,’ the palaeontologist added.

What is most interesting about C. youngorum’s size, however, is the fact that the creature emerged only 3 million years after the first ichthyosaurs evolved from their land-based predecessors, developing fins and a hydrodynamics form.

‘That’s an amazingly short time to grow that big,’ Professor Sander explained.

It was in the September of 2011 that palaeontologists excavated out of the rocks of Nevada’s Augusta Mountains a well-preserved (and 6.6-feet-long) fossil skull (pictured, with NHM Dinosaur Institute volunteer Viji Shook for scale), forelimbs and chest bones of the ichthyosaur

To find out how C. youngorum got so large, the researchers used ecosystem modelling to explore the energy flows in the local food web of the time.

‘One rather unique aspect of this project is the integrative nature of our approach,’ said paper author and palaeobiologist Lars Schmitz of California’s Scripps College.

‘After describing the anatomy of the giant skull in detail and thus understanding how this animal is related to other ichthyosaurs, we wanted to understand the significance of the new discovery in the context of the large-scale evolutionary pattern of ichthyosaur and whale body sizes.

‘To do this, we needed to figure out how the fossil ecosystem preserved in the Fossil Hill Member may have functioned.’

Fossil remains of C. youngorum were first unearthed in the Augusta Mountains (pictured) back in 1998 — specifically in the form of fragments of the creature’s spine

Analysis suggested that the waters of Nevada were once suited to the development of such gigantism — being rich in eel-like conodonts and ammonites (relatives of squid and cuttlefish) — and may have supported a still larger ichthyosaur as well.

‘To understand the functioning of this food web from ecological modelling was very exciting,’ said paper author and evolutionary ecologist Eva Maria Griebeler of the University of Mainz, who led the modelling effort.

‘Due to their large size and resulting energy demands, the densities of the largest ichthyosaurs from the Fossil Hill Fauna including Cymbospondylus youngorum must have been substantially lower than suggested by our field census.’

Unlike the evolution of modern whales, which rose in size slowly over their history, ichthyosaurs appear to have undergone a sudden boom, the team said.

‘We assume that ichthyosaurs were also able to evolve so rapidly because they were the first larger creatures to populate the world’s oceans and were exposed to less competition,’ added Professor Sander.

In contrast, the development of whales was driven by the availability of various types of plankton — alongside the adoption of different feeding specialisations.

Analysis suggested that the waters of Nevada were once suited to the development of such gigantism — being rich in eel-like conodonts and ammonites (relatives of squid and cuttlefish) — and may have supported a still larger ichthyosaur as well. Pictured: an ichthyosaur fossil surrounded by the shells of ammonites, the food source that possibly fuelled their gigantism

Both ichthyosaurs and whales, however, relied on exploiting niches in the good chain in order to reach such colossal sizes.

‘This discovery and the results of our study highlight how different groups of marine tetrapods evolved body sizes of epic proportions under somewhat similar circumstances, but at surprisingly different rates,’ said Jorge Velez-Juarbe.

‘Cymbospondylus youngorum and the rest of the Fossil Hill Fauna are a testament to the resilience of life in the oceans after the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history,’ the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County expert added.

‘You can say this is the first big splash for tetrapods in the oceans.’

With the study complete, C. youngorum has entered into the palaeontological collections of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, where it is presently on display to members of the public.

A facsimile of the creature’s skull is also being prepared for display in the Goldfuß Museum at the University of Bonn.

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Science.

The fossil was extracted from a layer of Middle Triassic-aged rocks known as the Fossil Hill Member that outcrops in the remote Augusta Mountains

What we know about ichthyosaurs — marine predators that ruled the waters in the era of the dinosaurs

Ichthyosaurs were a highly successful group of sea-going reptiles that became extinct around 90 million years ago.

They appeared during the Triassic, reached their peak during the Jurassic, and disappeared during the Cretaceous period.

Often misidentified as swimming dinosaurs, these reptiles appeared before the first dinosaurs had emerged.

They evolved from an as-yet unidentified land reptile that moved back into the water.

The huge animals, which remained at the top of the food chain for millions of years, developed a streamlined, fish-like form built for speed.

Scientists calculate that one species had a cruising speed of 22 mph (36 kph).

The largest species of ichthyosaur is thought to have grown to over 20 metres (65 ft) in length.

The largest complete ichthyologists fossil ever discovered, at 11 feet (3.5 m), was found to have a foetus still inside its womb.

Scientists said in August 2017 that the incomplete embryo was less than seven centimetres (2.7 inches) long and consisted of preserved vertebrae, a forefin, ribs and a few other bones.

There was evidence the foetus was still developing in the womb when it died.

The find added to evidence that ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young, unlike egg-laying dinosaurs.

Source: Read Full Article