Richard C. Lewontin, widely considered one of the most brilliant geneticists of the modern era and a prolific, elegant and often caustic writer who condemned the facile use of genetics and evolutionary biology to “explain” human nature, died on Sunday at his home in Cambridge, Mass. He was 92.

His son, Timothy, said that the cause was unknown, but that Dr. Lewontin had not been eating for some time.

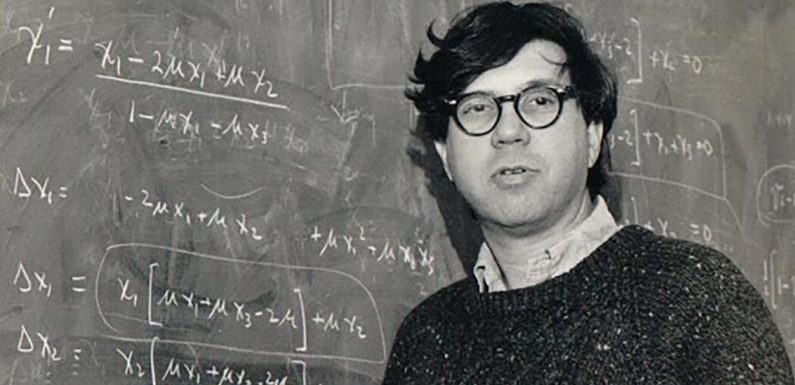

A pioneer in the study of genetic variation among humans and other animals, Dr. Lewontin spent the bulk of his career at Harvard University. Many of his students and colleagues regarded him with an awe that tipped toward reverence, describing him as equally gifted at abstruse quantitative research, popular writing and public speaking; a Renaissance scholar who spoke fluent French, wrote treatises in Italian, worked with Buckminster Fuller on his geodesic domes and played chamber music on the clarinet with his pianist wife, Mary Jane. He was also a volunteer firefighter and a self-described Marxist who chopped his own wood.

Not everyone was enamored of Dr. Lewontin. He famously clashed with another eminence and literary light at Harvard: Edward O. Wilson, a founder of sociobiology, the field that seeks to trace the roots of behavior in evolution. Dr. Lewontin considered Dr. Wilson a naïve genetic determinist and once derided him as a “corpse in the elevator.”

Because the two men worked in the same building, elevators were in fact a problem. “If you happened to be in an elevator with Wilson and Lewontin together, it was a most uncomfortable ride,” said Jerry Coyne, an evolutionary biologist now at the University of Chicago who studied under Dr. Lewontin. “Here were these two Harvard professors who wouldn’t even look at each other.”

In fact, Dr. Lewontin seemed to relish a good intellectual skirmish from all comers. Describing his experience studying under the great evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, Dr. Lewontin once said: “He and I spent three years of my Ph.D. fighting with each other. He liked it, and I liked it.”

Dr. Lewontin’s barbs, however, struck some as excessively harsh, especially from his highly visible perch as a regular and stylistically irresistible contributor to The New York Review of Books and other elite publications.

“Dick was a complicated man,” the primatologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy wrote in an email, “generous to his students, grossly unfair in his criticisms of Ed Wilson and the then-fledgling field of sociobiology.” Could this have had less to do with scientific specifics, Dr. Hrdy wondered, than with “plain old male-male competition?” To which Dr. Lewontin might well have pulled out his volunteer fireman’s hat: When it comes to the persistence of biological determinism, he wrote in 1994, no sooner has one fire been extinguished “by the cool stream of critical reason than another springs up down the street.”

Dr. Lewontin first won scientific fame in the mid-1960s for research he conducted with John Hubby at the University of Chicago that revealed far greater genetic diversity among members of the same species than anybody had suspected.

That work upended existing notions that most genetic mutations are rare, harmful and soon swept from the breeding pool. The two men’s findings showed that, to the contrary, many different forms, or alleles, of the same genes can coexist indefinitely in wild populations of organisms, be they fruit flies, zebra finches, earthworms or zebras. The quest to understand the reasons for all this allelic variety, and to understand precisely how it is maintained over time, remain lively and often contentious fields of research today.

Dr. Lewontin’s scientific renown expanded further in 1972, when he published a groundbreaking analysis of genetic variability in humans. His report showed that while individual people might differ genetically from one another, the same was less true for human groups or human races.

Using what would now count as relatively crude genetic markers like blood groups, but pulling from a significant global database, Dr. Lewontin and his co-workers determined that the great bulk of human genetic variability, roughly 85 percent, could be found within a population of, say, Asians or Africans, while just 15 percent of the diversity might distinguish Asians from Africans from Caucasians.

“People had expected to find lots of genetic differences between groups,” Andrew Berry, a lecturer at Harvard who studied under Dr. Lewontin, said. “They thought that Asians and Africans had been isolated from each other for such a long time they must have acquired all sorts of bespoke mutations.”

Dr. Lewontin found something very different: a distinct lack of differences. On a basic genetic level, Asians and Africans, as well as other racial and ethnic groups, are remarkably alike.

“The message is, despite the superficial differences we see among groups — the shape of the nose, the color of hair or skin, humans are stunningly similar,” Dr. Berry said. “This meshes beautifully with subsequent work that showed humans are a young species that only recently radiated out of Africa.”

Subsequent in-depth studies of DNA sequences have generally confirmed the remarkable large-scale genetic homogeneity of humanity that the Lewontin study revealed half a century ago.

Dr. Lewontin’s political activism grew in parallel with his scientific renown. He protested vigorously against the war in Vietnam, and in 1971 he quit the esteemed National Academy of Sciences, charging the organization with sponsoring secret military research.

He clashed with Edward Teller, considered the father of the hydrogen bomb, at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He called Dr. Teller “a flunky of power” and derided his notion that science is somehow purer and nobler than other pursuits and should remain above the fray. “Science is a social activity just like being a policeman, a factory worker or a politician,” Dr. Lewontin said.

He was no fan of the massive federal Human Genome Project, which set out to map the entire sequence of human DNA, and he strongly objected to the notion that DNA is the “blueprint” for a human being. He considered the perpetual debate over race, I.Q. and heritability to be an irritating scam, a recrudescence of Nazi-inflected notions of eugenics and master races.

Even to begin to figure out how big a role genes played in intellectual life, he said, would require a large number of newborn infants to be raised in tightly controlled circumstances by caretakers who had no idea where the babies came from. “We should not be surprised that such a study has not been done,” he added.

Dr. Lewontin marveled at the perniciousness of sexism, including among his supposedly high-minded peers. “When speaking to academic audiences about the biological determination of social status, I have repeatedly tried the experiment of asking the crowd how many believe that blacks are genetically mentally inferior to whites,” he wrote in 1994.

“No one ever raises a hand,” he continued. “When I then ask how many believe that men are biologically superior to women in analytic and mathematical ability, there will always be a few volunteers. To admit publicly to outright biological racism is a strict taboo, but the avowal of biological sexism is tolerated as a minor foolishness.”

Dr. Lewontin also criticized the adaptationist view of evolution — the idea that everything we see in nature has evolved for a reason, which it behooves biologists to divine. He collaborated with a Harvard colleague, Stephen Jay Gould, on a famous essay called “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Program.”

They argued that many seemingly important traits might have arisen incidentally, the tag-along result of other features they accompany — just as the spandrels, or spaces above arches, on the dome of San Marco were not put there to be richly decorated, but because you can’t make a dome without spandrels. Dr. Lewontin eventually grew disenchanted with Dr. Gould, however, for what he saw as Dr. Gould’s thirst for celebrity.

It was Dr. Lewontin’s break with another old friend, Dr. Wilson, that proved the more harrowing and long-lasting. Dr. Lewontin in 1975 attacked Dr. Wilson’s 700-page blockbuster, “Sociobiology: A New Synthesis,” as the work of a modern, industrial Western “ideologue.” Inspired by this and similar critiques, a group of demonstrators at a 1978 scientific meeting dumped a bucket of water over Dr. Wilson’s head.

The ill will persisted for many years, but friends said the two men had recently reconciled with a handshake, calling each other worthy adversaries.

More recently, Dr. Lewontin took on the field of evolutionary psychology. “It’s a waste of time,” he said. “It doesn’t count as science to me.” One of the chestnuts of the discipline is the notion that men are innately prone to straying, and will spread their seed with as many nubile young partners as will have them. While recognizing that anecdote isn’t evidence, Dr. Lewontin said, he certainly didn’t follow the E.P. male script. He married his high school sweetheart, Mary Jane Christianson, at age 18, ate lunch with her every day, read poetry with her at night, held hands with her in movie theaters and died just three days after she did.

In addition to his son Timothy, Dr. Lewontin is survived by three other sons, David, Stephen and James; seven grandchildren; and one great-grandchild.

“I want to make clear my own attitude,” Dr. Lewontin said in 2009. “I think most of the interesting questions about human individual and social behavior will never be answered. The human species will be extinct before they are.”

Richard Lewontin was born in New York City on March 29, 1929, the only child of Max and Lilian Lewontin. His father was a cloth broker who connected clothing mills with manufacturers; his mother was a homemaker. He earned a bachelor’s in biology at Harvard in 1951, a master’s degree in mathematical statistics at Columbia and a Ph.D. at Columbia in 1954.

Dr. Lewontin held faculty positions at North Carolina State University, the University of Rochester and the University of Chicago before moving to Harvard in 1973.

He had habits of dress: “Khaki pants, work boots, work shirt — in solidarity with workers,” Dr. Coyne said. He had habits of principle, notably of authorship: Many senior scientists are listed as authors on research reports done entirely by their students, but Dr. Lewontin would have none of it. If you didn’t do any of the work, he insisted, you don’t get to take any of the credit.

Scientists from around the world were drawn to him. They would gather in his laboratory around an old conference table beneath a mounted moose head and argue about population genetics, legitimate evolutionary theory versus dime-store Darwinism, economics, politics, history, and the debt that university scientists owe to the society that nurtured them.

He was the author of “It Ain’t Necessarily So: The Dream of the Human Genome and Other Illusions” (2000) and “The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment” (2000), among other books, and he loved writing his column for The New York Review of Books. He wrote easily and said he never did a second draft.

Yet Dr. Lewontin insisted that his legitimacy as a writer rested on his scientific contributions, and that the day he stopped doing science he would stop writing, too. In 2014, he kept his word.

Source: Read Full Article