Malaria parasite originated in African APES before evolving to infect people 5,000 years ago, study finds

- Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites spread by mosquitos

- Six parasite species are known to cause malaria in humans, including P. malariae

- P. malariae arose from a transmission of an ape parasite to humans, experts say

A malaria parasite originated in African apes before evolving to infect people, a new study shows.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have studied the parasite Plasmodium malariae – one of six species that spreads malaria among humans today.

P. malariae was originally an ape parasite, the researchers say, but mutated to be able to switch hosts and infect humans.

They say the species made the jump from apes to humans around 5,000 years ago, when agriculture was becoming established in sub-Saharan Africa.

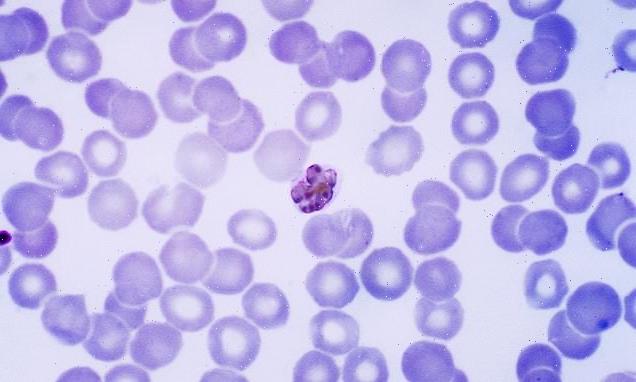

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh have studied the parasite Plasmodium malariae – one of six species that spreads malaria among humans. This photomicrograph shows a mature Plasmodium malariae cell within an infected red blood cell

SIX SPECIES SPREAD MALARIA AMONG HUMANS

– Plasmodium falciparum

– Plasmodium vivax

– Plasmodium ovale curtisi

– Plasmodium ovale wallikeri

– Plasmodium malariae

– Plasmodium knowlesi

‘Among the six parasites that cause malaria in humans, P. malariae is one of the least well understood,’ said lead author Dr Lindsey Plenderleith at the University of Edinburgh’s School of Biological Sciences.

‘Our findings could provide vital clues on how it became able to infect people, as well as helping scientists gauge if further jumps of ape parasites into humans are likely.’

Researchers describe P. malariae’s jump from other great apes to humans ‘recent’, even though it was 5,000 years ago.

‘For evolutionary biologists, 5,000 years ago is very recent,’ study author Professor Paul Sharp at Edinburgh told MailOnline.

‘In the past, there has been speculation whether some of the human malaria parasites have infected us since before we shared a common ancestor with chimpanzee (about 7 million years ago), or whether humans acquired the parasites more recently (tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago).

‘Modern humans evolved about 200,000 years ago in Africa. They emerged out-of-Africa into Asia, and then the rest of the world about 70,000 to 100,000 years ago.

‘Against this backdrop, 5000 years ago is very recent in human history.’

It’s already well known that malaria is caused by parasites in the Plasmodium genus. A Plasmodium parasite will spread to humans through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes.

When an infected mosquito bites, the parasite enters the blood and travels to the liver, where it develops for days to weeks before re-entering the blood.

People who get malaria are typically very sick with high fevers, shaking chills, and flu-like illness. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma and death.

The Edinburgh researchers say there are six parasitic species that cause malaria in humans, all of which are in the Plasmodium genus – including P. malariae and P. falciparum.

It’s well known that malaria is caused by parasites in the Plasmodium genus. A Plasmodium parasite will spread to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus (pictured)

P. falciparum is the deadliest of the six human malaria species and responsible for the majority of malaria related deaths.

Conversely, P. malariae is generally associated with mild or no disease, and frequently co-exists with other malaria parasites in multi-species infections.

WHO ENDORSES WORLD’S FIRST MALARIA VACCINE

In October 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the world’s first malaria vaccine, which could save hundreds of thousands of lives every year.

WHO recommended widespread use of the RTS,S malaria vaccine – developed by British pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) – for children in sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions with moderate to high levels of malaria transmission.

WHO said that data show the vaccine is safe and effective, and is feasible to deliver to rural parts of the continent.

While it is often associated with mild disease, if untreated P. malariae can cause long-lasting, chronic infections that may last a lifetime, according to the researchers.

‘However, the parasite can also persist chronically and recrudesce years or decades after the initial infection,’ they write in their paper.

Back in the 1920s, scientists identified chimpanzees infected by parasites that appeared identical to P. malariae under a microscope.

It was thought both parasites belonged to the same species, but this could not be verified as the genetic make-up of the chimpanzee strain hadn’t been studied.

For the new study, the team, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania, obtained DNA from faecal samples from wild apes, and from blood samples from chimpanzees in sanctuaries, all of whom had been infected with P. malariae.

‘The parasites are in the blood stream, and the DNA from the parasites also gets into their faeces,’ Professor Sharp said.

They then used ‘state-of-the-art’ techniques to sort through DNA sequence data on a computer.

They did not study the 1920s chimp strain, because there is no longer material available from those samples.

Researchers found that there are, in fact, three distinct species that were once thought to all be P. malariae.

P. malariae infects mainly humans, while the two others infect other members of the great apes.

One of the two ape-infecting parasites, called called P. celatum, was found in chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos across Central and West Africa.

This previously unknown species is only distantly related to P. malariae, the team say.

The other ape parasite species, called P. praemalariae, is much more closely related to P. malariae.

Around 5,000 years ago, the human malaria parasite population went through a genetic bottleneck – when a population is greatly reduced in size.

Its population temporarily shrank and most of its genetic variation was lost, but this likely paved the way for P. malariae to emerge.

‘It looks like the ape parasites cannot simply infect humans,’ Professor Sharp told MailOnline.

‘So it is likely the jump required a special mutation in an ape parasite, that then allowed it to infects humans.

‘The first human to be infected with this ape parasite would get (from a mosquito bite) only a small number of parasites, containing only a limited fraction of the genetic diversity present in the ape parasite species; this is the bottleneck.’

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

MALARIA IS A SERIOUS INFECTION SPREAD BY MOSQUITOES

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by Plasmodium parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of mosquitoes – specifically infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

There are six species of parasite that cause malaria in humans, two of which pose the greatest threat.

The first – P. falciparum – accounted for the majority of cases in Africa, the South-East Asia Region, Eastern Mediterranean and the the Western Pacific.

The second, called P. vivax, is the predominant parasite in the Region of the Americas.

Symptoms

Malaria is an acute febrile illness, which is generally defined as a fever that subsides by itself in three weeks. In the case of malaria, the fever is accompanied by headache and chills.

The symptoms may be mild to begin with, but if not treated within 24 hours, P. falciparum malaria can progress to severe illness, often leading to death.

Children with severe malaria frequently develop one or more of the following symptoms: severe anaemia, respiratory distress, or cerebral malaria.

Multi-organ failure in adults is also frequent.

Who is at risk?

In 2019, nearly half of the world’s population was at risk of malaria.

Most malaria cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa, but South-East Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific and Americas are also at risk.

The groups at highest risk include: infants, children under the age of five, pregnant women and patients with HIV/AIDS, as well as non-immune migrants and mobile populations.

Prevention and treatment

There are a number of ways to prevent malaria, with ‘vector control’ – the control of the mosquitoes themselves – being seen as the most effective.

The WHO recommends insecticide-treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying – as being effective against the insects.

Antimalarial medicines can also be used to prevent malaria, such as chemoprophylaxis, which suppresses the blood stage of malaria infections, thereby preventing malaria disease.

Vaccines

There is currently only one vaccine to date that has shown it can significant reduce malaria, and life-threatening severe malaria, in young African children – RTS,S/AS01 (RTS,S).

It acts against P. falciparum, the most deadly malaria, and is found to prevent approximately 4 in 10 cases.

Source: World Health Organization

Source: Read Full Article