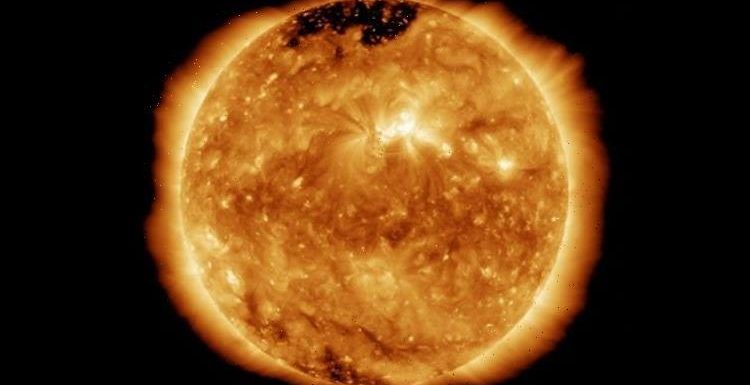

Solar storm could cause ‘catastrophic damage’ to UK

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

A major solar storm has not struck the planet in more than 160 years, although one came dangerously close in 2012. Triggered by powerful episodes of activity on the Sun, solar storms have the power to wipe out satellites and destabilise power grids across swathes of the planet. When the infamous Carrington Event struck in 1859, a monstrous blast of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun is said to have set telegraph poles sparking all across Europe and North America.

Should an event like that repeat today, scientists from the US fear the whole of the country would be brought down to its knees.

Gabor Toth, Professor of Climate and Space Sciences and Engineering at the University of Michigan, said: “There are only two natural disasters that could impact the entire US.

“One is a pandemic and the other is an extreme space weather event.”

Solar storms occur on a fairly regular basis they are rarely powerful enough to fry electronics.

According to the US Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), Minor G1 class storms may cause some weak disturbances to satellite operations.

But at the far end of the scale – Extreme G5 – storms and entire power grids are at risk of collapsing.

When the Carrington Event unfolded in 1859, the world was nowhere near as technologically advanced as it is today.

Satellites ensuring high-speed communications weren’t circling the globe and electricity was not a widespread commodity for another 60 years or so.

The Earth got a taste of what could happen during such an event in 1989 when a strong period of geomagnetic unrest caused a nine-hour outage of the Hydro-Québec’s power grid.

The blackout left millions of people in Canada without access to electricity.

Solar storm: NASA captures the moment a sunspot 'explodes'

Professor Toth said: “We have all these technological assets that are at risk.

“If an extreme event like the one in 1859 happened again, it would completely destroy the power grid and satellite and communications systems – the stakes are much higher.”

Because of the dangers posed by heightened solar activity, scientists have launched an initiative to develop new forecasting models for hazardous space weather.

Dubbed the Space Weather with Quantified Uncertainties (SWQU) programme, the initiative was created last year by NASA and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Among the proposed solutions to the problem is a forecasting model developed by Professor Toth and his teams at the University of Michigan.

An upgraded version of the model has been in use by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) since February this year.

The so-called Geospace Model Version has been upgraded to the 2.0 version, replacing the 1.5 model used since 2017.

The tool predicts disturbances on the ground that are caused by interactions with solar winds – a stream of charged particles venting from the Sun and out into space.

The disturbances caused by solar winds interacting with the magnetosphere – region of space dominated by Earth’s magnetic field – can cause damage to power grids, disrupt radio signals and knock out communication satellites.

Professor Toth said: “We’re currently using data from a satellite measuring plasma parameters one million miles away from the Earth.”

The researchers are particularly interested in observing coronal mass ejections or CMEs – large expulsions of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun’s corona.

A powerful CME is believed to have been responsible for the Carrington Event.

Professor Toth added: “That happens early on the Sun. From that point, we can run a model and predict the arrival time and impact of magnetic events.”

The expert and his colleagues run the forecasting model on the Frontera supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center in Austin.

New algorithms and the powerful supercomputer allow the researchers to run their models 10 to 100 times faster.

Professor Toth said: “People tried it before and failed. But we made it work.

“We go a million times faster than brute-force simulations by inventing smart approximations and algorithms.”

Source: Read Full Article