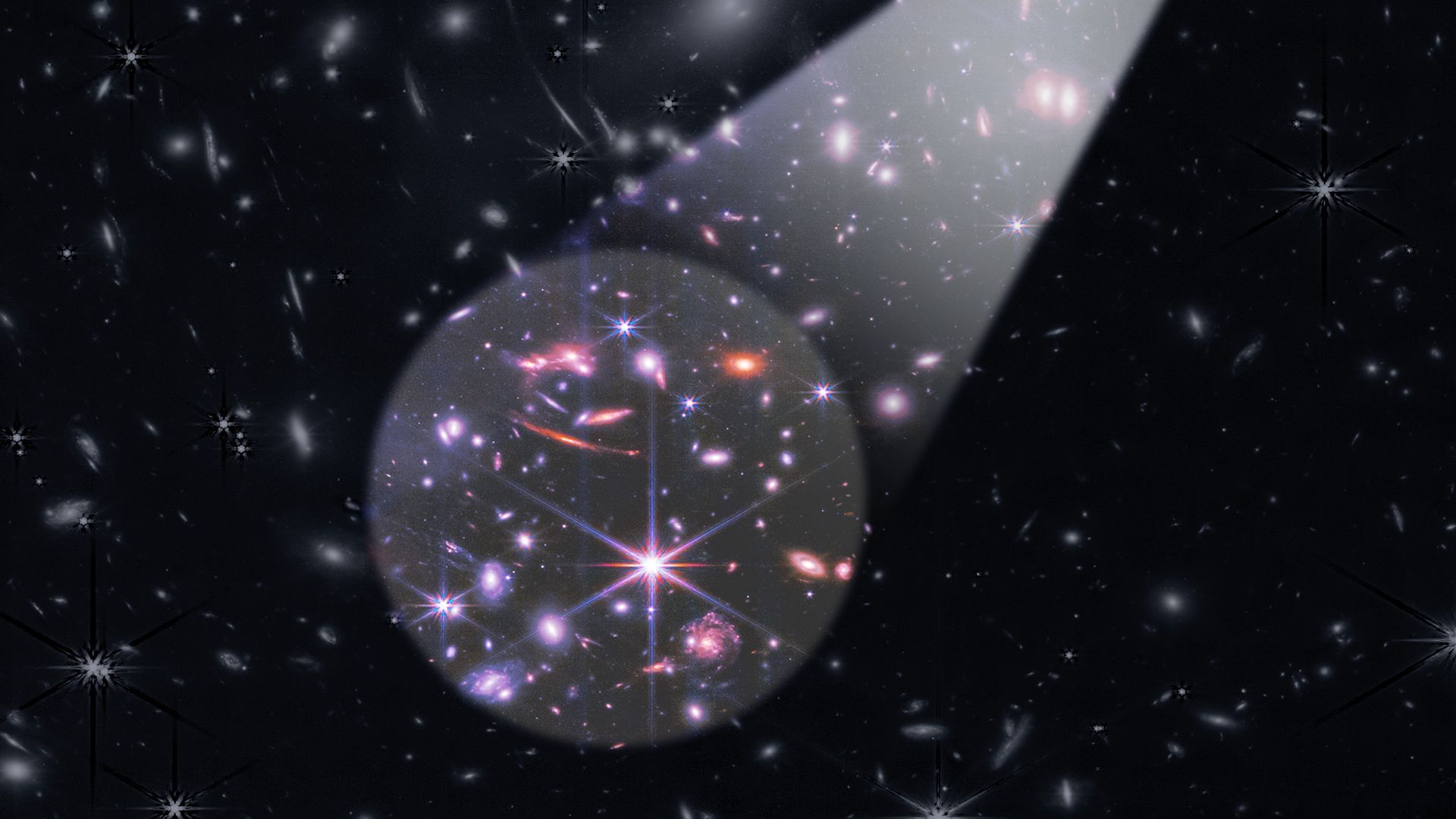

Photo illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI

The James Webb Space Telescope has been fully operational for less than a year, but its data is already hinting the early universe may have more galaxies — and more complicated galaxies — than many models have predicted.

Why it matters: A longstanding question in astronomy and astrophysics has centered on how the first generations of galaxies formed and evolved after the Big Bang.

- The JWST was built, in part, to answer those questions.

- "I think we're really seeing the ultimate origins of humanity," astronomer Steven Finkelstein, of the University of Texas at Austin, tells Axios. "These early galaxies are the sites where the earliest stars formed. They formed the first heavy metals in the universe. Those heavy metals eventually became our Earth and our bodies."

What's happening: One study submitted to the Astrophysical Journal looked at 850 galaxies that formed between 11 billion and 13 billion years ago, grouping them according to type — spiral, elliptical, irregular or a combination.

- The team found the proportion of galaxies by type was nearly the same as what they see in the nearby universe today. This could mean these galaxies were relatively far along in their evolution, despite the universe's young age.

- Another study published in the Astrophysical Journal in December found 87 galaxies that may have been around just 200 million to 400 million years after the Big Bang. This would be far more galaxies than scientists expected to see at this point in cosmic time.

- Even if only a relatively small number of those galaxies turn out to be real, astronomer Haojing Yan, one of the authors of the study said during a press conference last week, “then our previously-favored picture of galaxy formation in the early universe must be revised.”

The intrigue: The evidence there may be more galaxies in the early universe doesn't necessarily mean there's something wrong with the prevailing model of how the universe works that predicts how many early galaxies astronomers should see, Finkelstein says.

- But it does mean there's likely something about these early galaxies that needs to be re-examined.

- It could be that galaxies in these early eras of the universe were just brighter than initially expected, making it easier for scientists to see them in the data available now, Finkelstein says.

- Or, the stars forming in these galaxies might be hotter and brighter than expected, forming from metal-poor gas, which allows them to grow to massive sizes — and get hotter and brighter.

How it works: The truly revolutionary part of the JWST's technology is the telescope's ability to take a "spectrum" — effectively a chemical fingerprint of a galaxy's makeup — for even the most distant galaxies.

- That instrumentation allows scientists to see how much oxygen, hydrogen and other elements there are in any given galaxy, painting a picture of what may have been happening at that point in cosmic history.

- Chemical compositions of galaxies can also tell scientists how primitive galaxies might be, and a clutch of chemically primitive galaxies were recently found in data from the JWST.

- "All galaxies start with dark matter, hydrogen and helium, and then stars form," NASA's Sangeeta Malhotra tells Axios. "When stars do their nuclear powered thing, they form oxygen and other elements. … Having very little — or the littlest — quantity of oxygen tells us that this is a pretty young galaxy."

What to watch: As the JWST gathers more spectra and takes more images of distant galaxies, scientists will likely be able to start to resolve a true picture of what the universe was like billions of years before our Milky Way was born.

- "I think that in the next year or two, we're going to see a lot of further clarity on what the early galaxy population looks like," NASA's James Rhoads says.

Source: Read Full Article