Talk about a grizzly discovery! Bones found in Germany suggest ancient humans were skinning bears for their furs at least 320,000 years ago

- Experts studied bones of the cave bear, an extinct species from Europe and Asia

- The bones were discovered at the site of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany

- Researchers found very thin cutmarks on bones in the animal’s throat and foot

- This suggests that the animal was cut up for its skin as opposed to for its meat

Bear bones found in Germany suggest ancient humans were skinning the animals for their fur at least 320,000 years ago, researchers say.

Throat and foot bones that once belonged to an extinct cave bear were discovered at the Lower Paleolithic site of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Researchers found very thin cutmarks on the bones that ‘provide early evidence for the exploitation of bear skins’, they say.

The skin would have helped to keep the hunters warm so they were able to survive the European winters during the Old Stone Age.

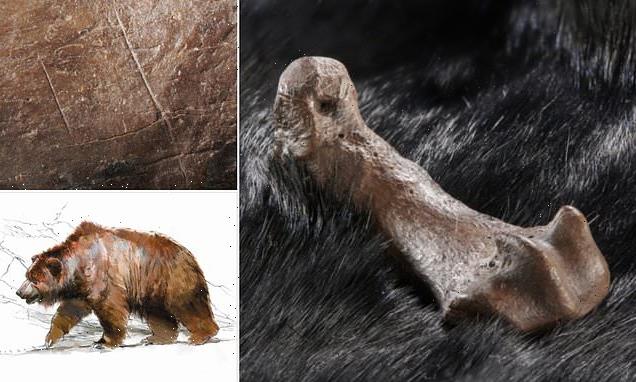

Humans have been using bear skins to protect themselves from cold weather for at least 300,000 years. This is suggested by cut marks on the metatarsal (pictured) and phalanx of a cave bear discovered at the Lower Paleolithic site of Schöningen in Lower Saxony, Germany

The cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) is a prehistoric species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch.

The species became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

In European cave deposits, the remains of more than 100,000 cave bears have been found.

Cave bear remains have been found in England, Belgium, Germany, Russia, Spain, Italy, and Greece, and the animal may have reached North Africa.

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

The new study was led by experts at the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment in Tübingen, Germany.

‘The very thin cutmarks found on the Schöningen specimens indicate delicate butchering and show similarities in butchery patterns to bears from other Paleolithic sites,’ they say in their paper.

The bones – which have already been dated to 320,000 years ago – belonged to a cave bear (Ursus spelaeus).

This prehistoric species of bear lived in Europe and Asia and became extinct about 24,000 years ago during the Last Glacial Maximum.

The species could reach more than 10 feet (three metres) in length and weigh more than one metric tonne during the ice ages, although cave bears in Schöningen during the summer would have been smaller than this.

As omnivores and frequent cave dwellers, cave bears shared their environments with humans, and interactions between humans and bears would likely have occurred.

However, the accumulation of large masses of cave bear remains, sometimes found in ‘peculiar constellations’ on the cave floor, has led to the interpretation that cave bears were actively hunted and worshiped as part of a cult.

It’s also likely that humans would have hunted cave bears for their meat; however, the position of cuts on these particular specimens – the metatarsal bones (in the foot) and the phalanx (in the throat) – suggest the bear’s skin was removed too.

The cutmarked bear metatarsal and phalanx from Schöningen ‘provide early evidence for the exploitation of bear skins’, the researchers say. Pictured, Detail of the precise and fine cut marks on the metatarsal of the cave bear

The cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) is a species of bear that lived in Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch. Image shows an illustration of the species, which could reach more than 10 feet in length (3 metres) and a weight of more than one metric tonne during the ice ages

Cave bear extinction was likely due to large sinuses that impaired chewing, study says

Cave bears may have become extinct because of their inability to chew meat due to their evolved large sinuses, a 2020 study said.

A cooling climate forced cave bears to develop large paranasal sinuses – the air-filled spaces within the bones of the skull – to allow for greater metabolic control during hibernation.

That evolution, in turn, changed the shape of cave bears’ skulls, potentially compromising their ability to chew, the authors said.

Read more

The very thin cutmarks found on the Schöningen bear bones indicate ‘delicate butchering’ that would have been necessary to remove the skin, the team say.

The throat and foot were unlikely to be cut for meat because there wouldn’t have been much meat on these parts of the body – suggesting that the whole of the bear was prized as a valuable resource.

‘Cut marks on bones are often interpreted in archaeology as an indication of the utilisation of meat,’ said study author Ivo Verheijen.

‘But there is hardly any meat to be recovered from hand and foot bones.

‘In this case, we can attribute such fine and precise cut marks to the careful stripping of the skin.’

Researchers point out that the insulating properties of bear skins would have made them ‘a highly valuable resource for survival in cold conditions’.

A bear’s winter coat consists of both long outer hairs that form an airy protective layer and short, dense hairs that provide particularly good insulation.

The bear skin had to have been removed shortly after the animal’s death, otherwise the hair and skin would have been damaged by the elements and by scavenging animals.

‘Since the animal was skinned, it couldn’t have been dead for long at that point,’ Verheijen said.

The team say Schöningen likely played a major role in the origin of active and specialized hunting of large mammals.

The oldest weapons reported in archaeological records – a set of 10 wooden throwing spears – have already been found at Schöningen.

Research has combined a fragment of a surviving spear found in Clacton-on-Sea (pictured) with javelin throwing athletes and found the projectiles were more efficient than previously thought

The so-called Schöningen spears could be used by hunters to kill animals at up to 65 feet (20 metres) away, a 2019 study found.

‘Schöningen plays a crucial role in the discussion about the origin of hunting, because the world’s oldest spears were discovered here,’ said Verheijen.

The new study has been published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

If you enjoyed this article…

First domesticated cats traced back 12,000 years ago, study finds

World’s oldest DNA discovered in Greenland dates back 2 MILLION years

Meet the odd hybrid animals that could be born because of climate change

Schöningen spears were used to kill prey from up to 65 feet away

A set of 10 spears found in Germany known as the Schöningen spears were used to kill prey from up to 65 feet (20 metres) away, scientists found.

The 2019 research combined a fragment of a surviving spear with javelin throwing athletes and found the projectiles were more efficient than previously thought.

Experts had originally assumed ancient hunters used their crude wooden spears for stabbing and lunging instead of throwing.

Using accurate replicas of Neanderthal spears dating back 300,000 years, the javelin throwers managed to hit a target up to 65 feet (20 metres) away.

This was double the distance scientists had believed the ‘Schöningen’ spears could be thrown.

In addition, the spears slammed into the target with sufficient force to kill prey.

The Schöningen spears are a set of ten wooden throwing spears from the Palaeolithic Age that were excavated between 1994 and 1999 in an open-cast lignite mine in Schoningen, Germany, together with approximately 16,000 animal bones.

The Schöningen spears represent the oldest completely preserved hunting weapons of prehistoric Europe so far discovered.

Source: Read Full Article