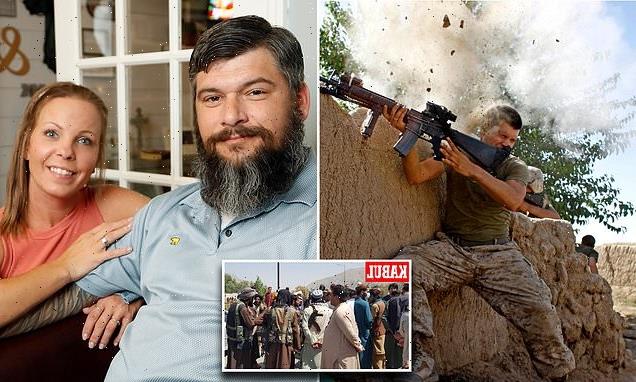

EXCLUSIVE: US Marine in iconic Taliban firefight photo says government didn’t learn a thing from Saigon as Kabul crumbles and doesn’t care about the 2,378 Americans killed in Afghanistan or the locals who have been abandoned

- Marine Staff Sergeant William Bee’s close call with a Taliban sniper is an iconic image from Afghanistan

- He was in Garmsir, Helmand Province, in 2008 when the bullet hit a wall just inches from his head

- Bee was one of the first Marines on the ground in Afghanistan after 9/11 and served four deployments

- Has watched in horror from his home in Jacksonville, North Carolina, as the insurgents took Kabul

- Bee now believes the government doesn’t care about the 2,378 Americans killed in Afghanistan

- He also said he couldn’t trust the Pentagon top command to ‘run a bath’ at the moment, let alone a war

- Bee is co-writing a book on his military career and life that is set for release in September 2022

Marine Staff Sergeant William Bee’s brush with death with a Taliban sniper has become one of the most iconic images from the War on Terror.

He was in Garmsir, Helmand Province, in 2008 when the bullet hit a wall just inches from his head while he wasn’t wearing a helmet or Kevlar vest.

Bee was one of the first Marines on the ground in Afghanistan after 9/11 and served four deployments in America’s longest war before an IED explosion and a traumatic brain injury in 2010 almost killed him and brought his career to a premature end.

The Purple Heart winner has been watching in horror from his home in Jacksonville, North Carolina, as the insurgents he risked his life fighting stormed into Kabul, took over the government he tried to keep stable and put the Afghan people he fought alongside at risk.

He believes the government doesn’t care about the Marines, friends and the 2,378 American service members who have been killed in Afghanistan since 2001 as western forces and diplomatic personnel flee and the country crumbles.

In an interview with DailyMail.com he said the Taliban will start executing citizens without trial and women will be stoned to death as they start to impose Sharia Law. He also said the administration didn’t learned anything from the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The images of helicopters flying from the US embassy in Kabul to Hamid Karzai International Airport has sparked flashbacks of the scramble to get onto flights out of Vietnam in the last days of the war.

He also said he couldn’t trust the Pentagon top command to ‘run a bath’ at the moment, let alone a war, and accused each president since 2002 of having no ‘clue how to remedy the chaos in Afghanistan’.

Bee now lives with his wife Bobbie and son Ethan near Camp Lejeune, where he watched the Twin Towers come down during boot camp.

He is co-writing a book on his military career set to be released in September 2022.

Marine Staff Sergeant William Bee’s brush with death with a Taliban sniper has become one of the most iconic images from the War on Terror. He has been watching in horror from his home in Jacksonville, North Carolina, as the insurgents he risked his life fighting against stormed into Kabul, took over the government he tried to keep stable and put the Afghan people he fought alongside at risk

‘After 20 years and 2,378 Marines, Sailors, Soldiers and Airmen, our Commander in Chief decided on the spur of the moment to completely retreat, with zero accountability of weapons, equipment, and most importantly those who’ve helped us fight the Taliban.

‘That’s 2,378 brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, husbands and wives. How the hell do we turn to the surviving family members and tell them their loved one died for nothing?

‘To this day we can walk the fields of France, point at the gravestones of the fallen Soldiers who seized Normandy and proudly say that those we lost helped stem the tides of Axis and the world is a better place for it.

‘For those we lost in Helmand, Kandahar, Garmsir and other areas, we can say nothing. Anyone who has ever dealt with the Taliban know, Sharia Law is on the way.

‘I guarantee, any individual whom has helped us in any way is going to be summarily executed with no trial. Any woman with any sense of individualism will be stoned. How do we know? We’ve all seen it happen throughout our tours.

‘I understand that all of this isn’t President Biden’s fault, that every leader since the initial defeat of the Taliban in the spring of ’02 hasn’t had a clue of how to remedy the chaos in that country.

‘It displays the lack of awareness of the combat environment that is held by those people that make the decisions.

‘We tried to fight a war with our hands tied behind our backs. In my last two deployments with 1st battalion 6th Regiment, I walked with legends, “The Deathwalkers” as we were called by one Taliban commander.

‘By the middle of 2010 we filled the role of detective, not Warrior. I can remember having to do gun-shot Residue Tests on dudes we knew were Taliban, because we were more afraid of offending someone by arresting them than we were of protecting service members.

‘Personally, I think if you gave me my pick of three Marine Gunnery Sergeants and a Private First Class then we could’ve fought that war in a more effective manner than the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Run a war? I wouldn’t trust them to run a bath at this point.

‘I think my favorite quote by John Stuart Mills comes into play: “War is an ugly thing but not the ugliest of things. The decayed and degraded state of Moral and Patriotic feelings which think nothing is worth war is much worse.

“A man who has nothing for which he is willing to fight, nothing for which he is ready to die, is a sad creature and can only be free if made and kept so by the exertions of better men than himself.”‘

Bee was just 19 when he flew into southern Afghanistan on Christmas Day 2001. He was stationed at Kandahar Air Base as the U.S. began their first ground operations against Al-Qaeda in response to their plot to bring down the World Trade Center.

He was excited to be one of the first ‘dudes’ on the ground to open up fighting.

But with three more tours in Afghanistan and a stint on the fences of Guantanamo Bay in between, his enthusiasm subsided.

On one night in 2008, he held the hand of American sniper who had been shot in the head while a medic sliced open his throat for an airway.

It was one of the deadliest years of the war, firefights came and went every day and he knew he was out there to protect the young Marines around him and get them home.

A US soldier points his gun towards and bellows at an Afghan civilian at the Kabul airport on Monday. Two armed Afghans have been killed by American troops at the airport

Afghan people climb atop a plane as they wait at the Kabul airport in Kabul on Monday

Desperate Afghan nationals tried to run onto RCH 885 as it took off from the airfield on Monday. Some were crushed by the C-17’s wheels and others clung to the fuselage as it took off

On May 18, 2008, the temperature was hovering around the 115 degree mark in Garmsir, as it did most days in the hostile region.

‘The position we were in had a large poppy field to the west, with a house roughly 150 meters away,’ he said.

‘To the north was a building we had to keep an eye on, we didn’t have any friendlies in that direction and it was about 50m.

‘The east was considered inside our area of influence, and directly next door to the south was the third platoon.’

Sergeant Bee had just finished a four-hour rotation as Sergeant of the Guard (SOG).

‘I had been relieved, and was doing my laundry – which consisted of a hand operated water-pump, a bar of soap, and an old metal bucket to wash and rinse with.

‘Then I heard a single shot, which drew my attention. It was a common occurrence to hear a burst of gunfire, but a single shot was a cause for concern. It meant someone was attempting to use accurate fire,’ Sergeant Bee said.

‘Not thinking about my gear, I immediately grabbed my rifle, which is never farther than one-arms distance from a grunt when in-zone.

‘I went to check on the Marine on post, an attachment to one of our squads from the Engineer Unit in our MEU.

‘An ember (embedded photographer) from Reuters, Goran Tomasevic, accompanied me. He attached himself to our platoon a few days prior.

‘He was a great guy to talk to. He had seen more combat than most grunts I know.

He went home after the sniper shot, but decided on one more tour to keep fighting alongside the Marines he wanted to keep safe so they could get back to their families.

‘When I checked on the Marine, I noticed movement in the building to our north, and immediately drew down on it, leaning against the wall to stabilize myself prior to taking the shot.

‘I noticed Goran getting ready to take a picture, but paid him no mind, I was more focused on dropping the guy I believed had maneuvered on our position and shot at one of our posts.

‘The second I had my sights on the window, the world went dark.’

Sergeant Bee woke up on a stretcher, surrounded by green smoke. He believes the Marine on post thought he was hit, so immediately called for our platoon sergeant, Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Orjuela (Gunny O.J., now Sergeant Major O.J.) to get him out of there.

They threw smoke grenades to obscure the team’s positions, as they evacuated him, thinking he was unconscious. But soon he assured them he was fine.

‘Goran then came over with a huge grin on his face,’ Sergeant Bee said.

‘He told me he had been testing a new lens on his camera, and had accidentally set the camera to sequence shot, and showed me the pictures.

‘I told them how cool they were, and he’d be looking at a Pulitzer for such an awesome photo. His reply, and I quote: “I am f****** Serbian, I would never get that”.’

His final deployment in 2010 didn’t end so well. He was deployed during Operation Moshtarak (Translated from Dari, a language spoken in Afghanistan, into Together), in the Battle for the town of Marjah, Helmend Province.

More than 15,000 troops from the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) were involved, making it the largest joint operation during the War on Terror.

Sergeant Bee was awarded the Purple Heart in August 2016 after years of campaigning with his wife Bobbie

Ethan was only 15 months old when his father left him for war again.

‘That deployment was one of the most intense times of my life. It was my fourth deployment to Afghanistan, and I had never seen anything like it in my life,’ he said.

During the previous tour Garmsir, they would be engaged in gun battles three times a day, at ranges from 200m to 300m, almost like clockwork.

But in Marjah, the firefights would come at completely unexpected times.

Sergeant Bee said it would get to the point ‘where we would actually use grenades to clear rooms and buildings’.

On June 8, two weeks before his platoon were set to leave for the main battle in Marjah, he led them out on a patrol to get a taster of what the weeks to come would be like.

Their patrol consisted of Sergeant Bee’s squad, their Platoon Commander Lt Thomas Malone, and two sergeants from 2/6-Sergeant Zachary Walters and Sergeant Derek Shanfield.

‘My intent of the patrol was to show the two sergeants what happened anytime we entered the southern area of our AO (Area of Operations). Any time my squad would roll up in that area, a white van and some mopeds would always show up.

‘They would position themselves far enough out so that our small-arms couldn’t reach, and then spread out to different areas.

‘I wanted the two sergeants to see what happened, so they would know how the Taliban operate in the area first-hand. We weren’t looking for a fight. We were too close to the end and I didn’t want to risk any of my guys.

Sergeant Bee selected a building to use as an observation area. He sent Lt Malone and Corporal Ponce (2nd in command), along with his fireteam, to a small building 50m north to act as an overwatch, in case they were under fire and had to leave in a hurry.

‘I put my guys all around the interior of the building looking out for any sign of movement, so they could advise once the enemy showed.

‘As I was talking with Shanfield and Walters on a small mound looking out, my DM (Designated Marksman), Lance Corporal Johnston called for my attention because he had a round jammed into his chamber and needed help getting it out.

‘I remember being frustrated with him, because it should have been a simple fix.’ It turned out, the jam saved Sergeant Bee’s life.

‘All I remember after I took a knee to help him was a roaring sound, and the sensation of my entire vision turning into what you would see if you were trying to look through a straw. The next thing I remember is waking up in a CAT scan machine, in a hospital.’

From what he heard about the incident, the Taliban had implanted IED’s outside of the building, that were large enough to blow the walls inward.

He said: ‘Almost every one of my Marines in the building had to get CASEVAC’d to Camp Dwyer – a forward operating base that had a hospital

‘Sergeants Shanfield and Walters were killed instantly.

‘My decision to place my Marines in that building, along with the fact that I failed to make my team leaders sweep the building with metal detectors, cost two lives, and caused the rest of them to be injured.

‘Some have heavy scars, some carry their scars on the inside, and some still have pieces of the wall stuck in their bodies to this day.’

Bobbie remembers that she was driving on the I-95 in Pennsylvania when she got the second, heartbreaking call of her husband’s military career.

She returned to their home in North Carolina to try and maintain some normalcy and got her friends to help look after Ethan, until her husband got back.

‘When he got home he was completely different. The person I said goodbye to is not the person that came home. We have since had to adjust to our new normal life.

‘He knows that he is not the same person that boarded that bus the second time.

‘But he’s alive, that’s what I keep saying, it could be a lot worse. We have friends that aren’t that lucky.

On the day of the platoon’s memorial, Sergeant Bee asked Sgt Shanfield’s family to come his house, with two Marines to support him.

‘I had to look his mother in the eye and explain how I got her son killed, ‘ he said. ‘That was the most difficult thing I’ve had to do in my life.’

Following his injury, he was sent through Bagram Air Field, Afghanistan, to Landstuhl, Germany, for treatment.

After two weeks, he was allowed home.

‘I had to go through rehab and therapy, along with a battery of tests. I had suffered a TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury), with brain damage to four sections of my brain, along with damage to my vestibular system (balance and senses) and hearing loss.’

Source: Read Full Article