This is a companion piece to our story, “A DEA Raid Meant to Clean Up a New Mexico Town. Instead, It Made Everything Worse,” about the ramifications of a 1999 raid in Chimayó, New Mexico. Both stories were originally published by Searchlight New Mexico and published here as part of an ongoing collaboration with Rolling Stone.

It’s almost a cliché to say the war on drugs has been an abysmal failure. “It was not designed to be helpful or compassionate or even solutions-based,” said Emily Kaltenbach, senior director of criminal legal and policing reform at the Drug Policy Alliance. “From the beginning, it was a war on class and race.” Drug arrests in America are universally credited with creating mass incarceration for poor people of color. From 1980 to 2019, the number of Americans jailed for drug offenses soared from 40,900 to 430,926 and cost an estimated $1 trillion.

Related Stories

A DEA Raid Meant to Clean Up a New Mexico Town. Instead, It Made Everything Worse

Purdue Pharma's Bankruptcy Plan Is Approved, Allowing the Sackler Family to Escape Legal Accountability for the Opioid Crisis

Related Stories

Muhammad Ali: 4 Ways He Changed America

20 Overlooked Bob Dylan Classics

Close to 80 percent of federal and 60 percent of state prisoners who are incarcerated for drug offenses are Black or Latino, the vast majority of them for nonviolent crimes like possession or small-time dealing to support their habit.

In the backdrop, New Mexico, like other places, suffers from a perennial lack of quality treatment programs. A 2018 study found that 134,378 people in the state — including 863 people in Rio Arriba County — needed substance-abuse treatment and didn’t get it.

Meanwhile, the marketplace for drugs — both legal and illegal — continues to flourish in cities, rural areas and suburbs alike, shapeshifting to meet demand. “Criminalization doesn’t change behavior or get to the root of why people are selling or using drugs in the first place,” Kaltenbach said.

Some people in the Chimayó bust say they weren’t drug dealers. Corpentino Vigil, 56, said he’d never even used drugs until he was behind bars. (Illicit drugs are common in many lockups.) He’d pleaded guilty to dealing cocaine despite being innocent of the charges, Vigil said shortly before his death in September, of an undisclosed illness. He cycled in and out of the criminal justice system for the next two decades. Before the bust, he’d been a custodian at Chimayó Elementary School, a school bus driver and a boys basketball coach. Afterward, he found it impossible to get back on his feet. “Ever since then, I’ve been in trouble,” he said.

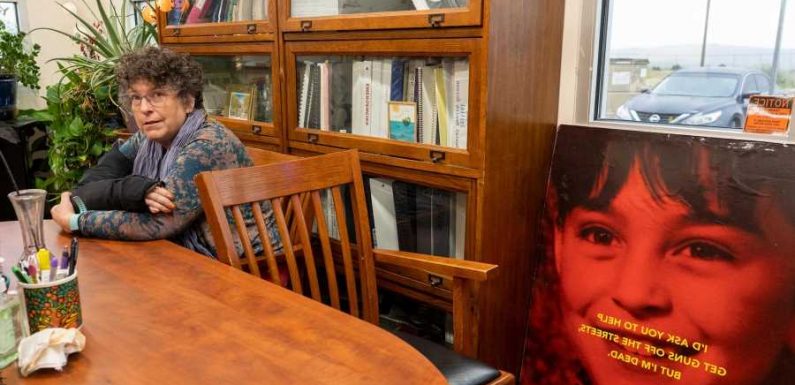

Chimayó has been in trouble, too. It sought help for its addiction problem all those years ago, and in return it received armed interference and a reputation as “the poster child” for the rural war on drugs, as Lauren Reichelt, director of Rio Arriba County’s Health and Human Services Department, put it. Heroin was cast as a lone villain — a solitary killer on the loose. In truth, most fatal overdoses occurred because people were mixing multiple substances, such as heroin, alcohol, prescription opioids and benzos like Valium. Reichelt, who explored overdose data for a 2002 study, said that from 1991 to 2001, not a single accidental overdose death involved the presence of only one drug. Similar studies around the nation link the majority of overdose deaths to a combination of substances, both illegal and legal.

“We didn’t have a heroin problem,” Reichelt said. “We had an addiction problem. And the DOJ was completely overlooking the most easily accessible culprits — alcohol and pharmaceutical companies.”

In fact, the late ’90s saw several area doctors lose their licenses because of overprescribing. (One was found to have prescribed 17,000 Percocets and 10,000 Valium pills to a single patient.) The loss of these “pill mills” created a complicated landscape of desperation just as black tar heroin was making its way to Northern New Mexico. Illicit drug use soared when access to legal drugs was cut off.

Reichelt recalled testifying at Sen. Pete Domenici’s 1999 Senate hearing in Española, a pivotal event in the lead-up to the bust. Before the hearing, an aide from Domenici’s office visited her and sternly told her not to discuss anything but heroin, she said. “It was like a scene out of Dr. Strangelove.” One speaker at the hearing beseeched Domenici not to allow the war on drugs to become “a war on our relatives.” But in the end, that’s what happened.

Source: Read Full Article