“I am approaching the world of art as an outsider, being a Black woman from the Caribbean,” Gio Swaby says over the phone from Toronto, where she is currently finishing up her master of fine arts degree at Ontario College of Art & Design University. “[Art] can be intimidating when you feel like you don’t have enough knowledge about something, or you feel like the space is not for you,” she continues. “I want my work to say that this space is for you, and it’s okay to connect with this work on any level that you do.”

The 30-year-old Bahamian multimedia textile artist took the art world by storm after her debut exhibition in New York City’s Claire Oliver Gallery, “Both Sides of the Sun,” sold out before it officially opened in April 2021. Since then, she has participated in two major art fairs (1-54 Art Fair in London and Untitled Art in Miami), and at least six major national museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, have added her work to their collections. This month, Rizzoli is publishing a monograph of her work to coincide with her first solo museum exhibition, “Fresh Up,” which will open at the Museum of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, Florida, on May 28.

Textiles are a great way to make the work a little bit more accessible, and accessibility is at the core of what I’m doing.

Swaby’s vivid textile portraits and mixed-media silhouettes are a love letter to Black women. Her practice, which she describes as “an exploration of love,” uses quilting and stitching techniques to portray Black women in moments of joy. Her life-scale threaded line works are stitched on the reverse side of the canvas to showcase the loose knots and threads—a reference to her subjects’ complexity and her method of embracing, as she explains, “the beauty in imperfection.” For the vibrant silhouettes of her female friends and family members that capture Black joy, she sews together pieces of fabric in bold prints to showcase their individuality and personal style. It’s her way of redefining the public discourse on Black women, whom the media often portrays in moments of profound sadness and whose images are frequently linked to violence and trauma.

“I feel like especially in 2020, we were exposed to so many images of Black people experiencing extraordinary suffering,” Swaby says. “It really takes a toll on you, because at that moment, you see yourself reflected. It’s really, really a difficult experience.” She continues, “And so [with] my work, I wanted to contribute to a counteracting of these moments where we’ve been depicted in our lowest moments and create a space where we can be empowered, where we can exist, just as we are, in this space full of love and also full of joy.”

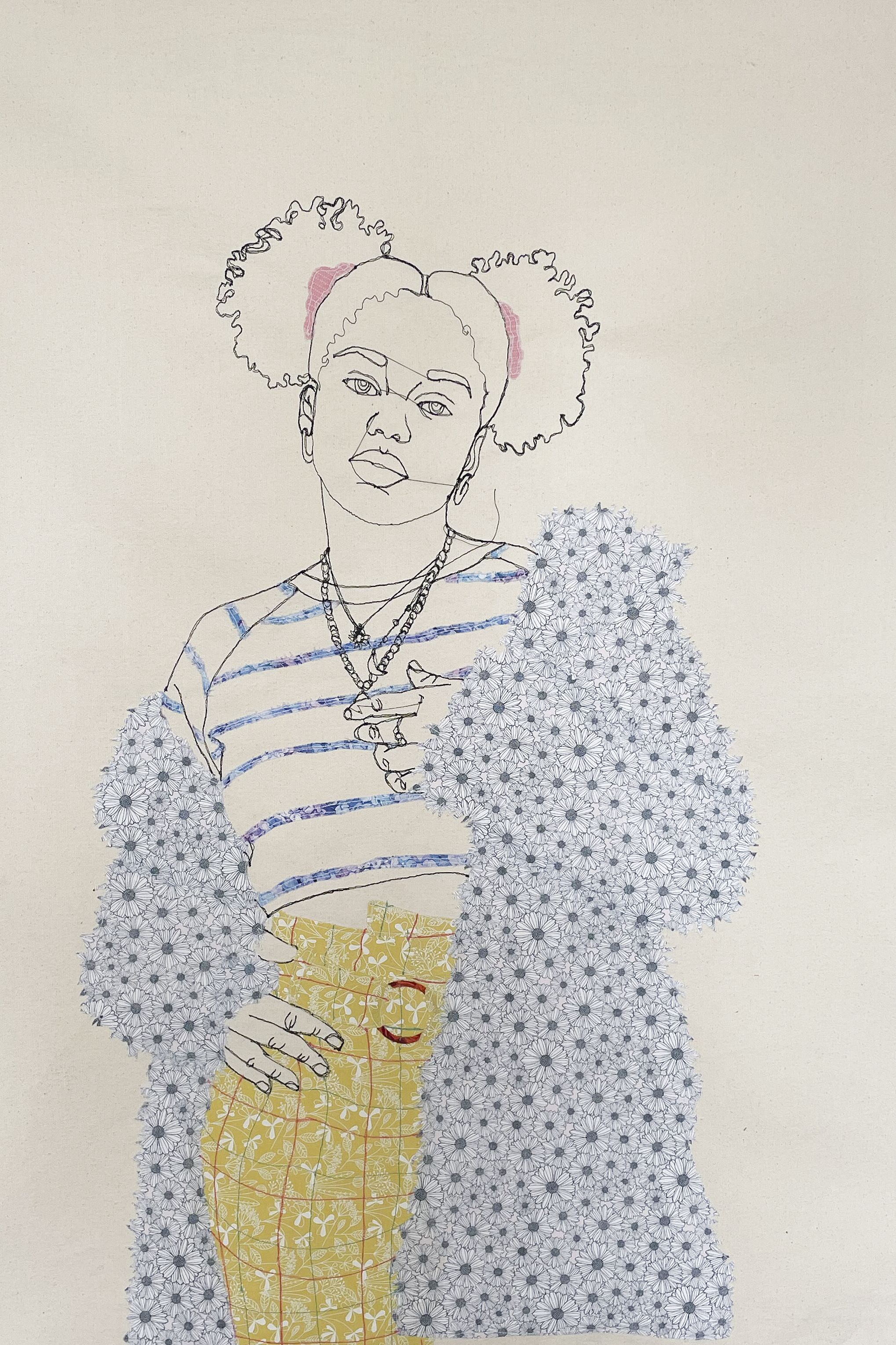

Fashion and style are essential components of Swaby’s work. In her full-length line portrait, Pretty Pretty 5, the subject wears a long-sleeved off-the-shoulder shirt and overalls, as well as platform combat boots rendered in cotton fabric with a blue and purple watercolor-like print. And in Another Side to Me Second Chapter 3, a young woman wears a floral coat over a striped crop top and a belted high-waist skirt in a yellow floral print. Her hair is styled in pigtails, and she touches a necklace with her left hand.

For Swaby, style—including hair and jewelry—is a visual way to capture the layers and nuance that Black women possess. She also sees personal style as a tool of resistance against “being unseen” and explores it as a way to navigate “the contradictory experience of invisibility and hypervisibility.” Ultimately, “it is about reclaiming space through unapologetic self-expression,” she explains.

Melinda Watt, chair and curator of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Textiles department, aligns Swaby’s artistic style with that of fiber artist Bisa Butler, known for her life-size historical quilts and portraits, and of Faith Ringgold, the groundbreaking African American multidisciplinary artist famous for her narrative quilts. Similarly, by using sewing, stitching, and fabric, Swaby expresses ideas about identity, culture, and family.

Swaby grew up in sunny Nassau in a household dominated by women; her mother was a seamstress who raised her, her three older sisters, and her younger brother as a single mom. As a child, she would sew clothes for her dolls with her mother.

When [Black women] look at my work, I want them to see themselves in a way that feels honest and full.

In college, Swaby worked with more traditional mediums: While earning her associate of arts degree at the College of the Bahamas, which she graduated from in 2012, she focused on paint and ceramics. Later, while getting her bachelor of fine arts degree at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, Canada, she began to experiment with film and video. But the following year, during a residency at independent studio and gallery Popop Studios in Nassau, she met a quilter who showed her various sewing techniques. She soon realized that working with textiles was the medium that brought her the most joy—and closer to her roots. “Textile art just made sense because, for me, it stems from a practice of love, learning from my mother, and sharing that together,” explains Swaby, who created her first textile portraits in 2013.

After graduating from Emily Carr University in 2016, Swaby stayed in Vancouver, and over the next few years participated in several group exhibitions, including a solo show at UNIT/PITT Projects. During an event, she met the curator Danielle Krysa, who ended up introducing her to gallery owner Claire Oliver. “I was gobsmacked,” Oliver remembers of her initial reaction to Swaby’s work. In fact, she was so impacted that she signed the artist without ever meeting her in person—a first in her 30-year career.

After sending out a mass email to her clients to announce representation of Swaby, Oliver’s phone started blowing up. “It was ringing, ringing, ringing—everything sold as quickly as I could answer the phone,” she remembers. “I was like, ‘People are responding to this work.’ It’s not just me that loves it,'” Oliver says, noting that author Roxane Gay was the first person to buy one of Swaby’s pieces.

Despite its popularity among industry insiders, the real power of Swaby’s art is that it transcends the tastes of collectors and effortlessly connects with the general public. This is something she, in part, credits to her medium of choice: textiles. “They’re part of our everyday lives. We come into contact with them all the time,” Swaby explains. “Quilting [is also traditionally] a very family-oriented experience,” she continues. “Textiles are a great way to make the work a little bit more accessible, and accessibility is at the core of what I’m doing.”

As Swaby points out, a key component of accessibility is representation, not only in terms of the subjects depicted in artworks, but also in terms of the artists who create them. Swaby likes to quote novelist Toni Morrison, who said, “I wrote my first novel because I wanted to read it.” She remembers how important it was for her to meet other Black artists from the Bahamas like Lillian Blades and Kendra Frorup, and how powerful it was to visit the Queens Museum in New York City in 2012 and see works by Jamaican artist Ebony Patterson. “She has such a distinct aesthetic that just feels so Caribbean,” Swaby says of Patterson’s work.

Swaby hopes her own practice can offer that same moment to other Black women. “When they look at my work, I want them to see themselves in a way that feels honest and full,” she says. “I want them to see the other Black women in their lives that they love and admire so much.”

Source: Read Full Article