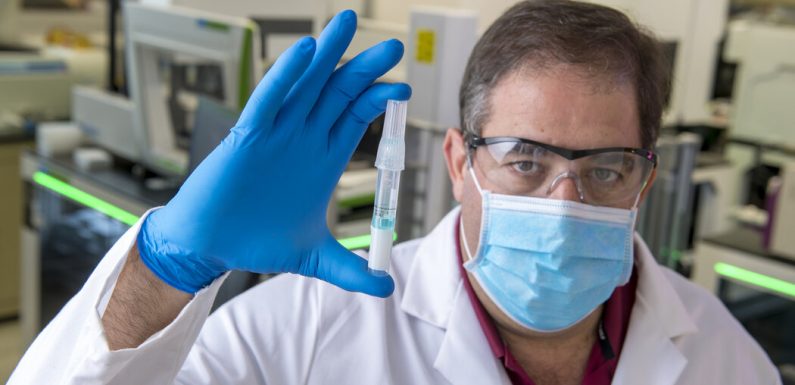

His breakthrough helped millions get their results quickly in the early days of the pandemic, when tests were scarce and lines were long.

By Clay Risen

Andrew Brooks, a research professor at Rutgers University who developed the first saliva test for Covid-19, died on Jan. 23 in Manhattan. He was 51.

The cause was a heart attack, his sister, Janet Green, said.

In April 2020, when Covid tests were scarce and lines to get them were long, Dr. Brooks made worldwide news when the Food and Drug Administration gave emergency approval to his technique, which promised to radically increase the speed and safety of the testing process.

“Instead of having a naso- or oropharyngeal swab that’s placed in your nose or the back of your throat, you simply have to spit in a tube,” he told Bill Hemmer of Fox News adding, “It doesn’t require a health care worker to collect it, six inches away from an infected person.”

In the 10 months since Dr. Brooks received approval, health care workers have performed more than four million tests using his approach, and it remains one of the most reliable means of determining whether someone has Covid.

In a statement after Dr. Brooks’s death, Gov. Phil Murphy of New Jersey called him “one of the state’s unsung heroes” who “undoubtedly saved lives.”

Andrew Ira Brooks was born on Feb. 10, 1969, in Bronxville, N.Y. His father, Perry H. Brooks, was a diamond setter. His mother, Phyllis (Heitner) Brooks, was a teacher.

In addition to his sister, he is survived by his mother; his wife, Jil (Larsen) Brooks, and three daughters, Lauren, Hannah and Danielle. His first two marriages ended in divorce.

Dr. Brooks grew up in Old Bridge, N.J., where he earned spending money by performing magic shows at birthday parties. Though he was adept at tricks involving doves and rabbits, his real forte was close up handwork, especially card tricks.

He played varsity golf at Cornell, where he initially planned to become a veterinarian, and majored in animal sciences. But after a summer internship at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, he became fascinated with the study of human disease. He received a doctorate in microbiology and immunology from the University of Rochester in 2000.

After working at the University of Rochester Medical Center for four years, he returned to New Jersey to take a job at Rutgers, and in 2009 joined its Cell and DNA Repository, a university-owned company that provides data management and analysis for biological research.

Latest Updates

Dr. Brooks became the company’s chief operating officer, and discovered he had a flair for the business side of science. He grew the company from just a few dozen employees to nearly 250, working with nearly every major pharmaceutical company, among other clients.

The Coronavirus Outbreak ›

Words to Know About Testing

Confused by the terms about coronavirus testing? Let us help:

-

- Antibody: A protein produced by the immune system that can recognize and attach precisely to specific kinds of viruses, bacteria, or other invaders.

- Antibody test/serology test: A test that detects antibodies specific to the coronavirus. Antibodies begin to appear in the blood about a week after the coronavirus has infected the body. Because antibodies take so long to develop, an antibody test can’t reliably diagnose an ongoing infection. But it can identify people who have been exposed to the coronavirus in the past.

- Antigen test: This test detects bits of coronavirus proteins called antigens. Antigen tests are fast, taking as little as five minutes, but are less accurate than tests that detect genetic material from the virus.

- Coronavirus: Any virus that belongs to the Orthocoronavirinae family of viruses. The coronavirus that causes Covid-19 is known as SARS-CoV-2.

- Covid-19: The disease caused by the new coronavirus. The name is short for coronavirus disease 2019.

- Isolation and quarantine: Isolation is the separation of people who know they are sick with a contagious disease from those who are not sick. Quarantine refers to restricting the movement of people who have been exposed to a virus.

- Nasopharyngeal swab: A long, flexible stick, tipped with a soft swab, that is inserted deep into the nose to get samples from the space where the nasal cavity meets the throat. Samples for coronavirus tests can also be collected with swabs that do not go as deep into the nose — sometimes called nasal swabs — or oral or throat swabs.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Scientists use PCR to make millions of copies of genetic material in a sample. Tests that use PCR enable researchers to detect the coronavirus even when it is scarce.

- Viral load: The amount of virus in a person’s body. In people infected by the coronavirus, the viral load may peak before they start to show symptoms, if symptoms appear at all.

Source: Read Full Article