Darwin’s short-beak enigma is SOLVED: Scientists discover a gene linked to beak size in pigeons that causes some breeds to develop flat faces

- A mutation in a gene called ROR2 is linked to beak length in domestic pigeons

- The gene explains why one species of pigeon has beaks of all shapes and sizes

- It also has a connection with Robinow syndrome, a human congenital disorder

Scientists have discovered the gene that causes some pigeons to develop flat faces – a conundrum that fascinated legendary British naturalist Charles Darwin.

In a new study, the academics report that mutations in the gene, called ROR2, are linked to beak size reduction in numerous breeds of domestic pigeons.

This finally explains why the 350-plus breeds of domestic pigeons of a single species (Columba livia) have beaks of all shapes and sizes.

Researchers bred two breeds of pigeon – one with a short beak and another with a longer beak – and did a genetic analysis of their offspring.

Surprisingly, mutations in ROR2 also underlie a human congenital disorder called Robinow syndrome, the researchers also found.

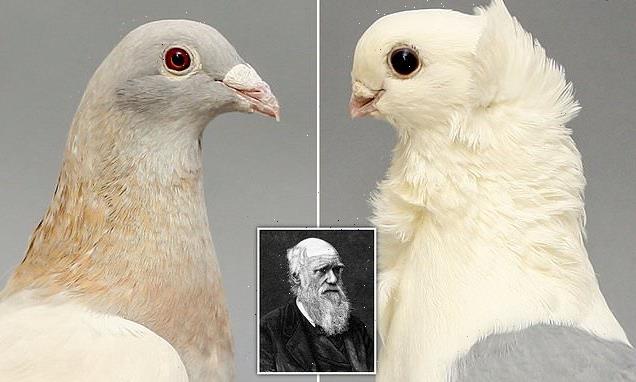

Old German Owl (left) and Racing Homer (right) – domestic pigeon breeds that the researchers bred for the study

DARWIN’S SHORT BEAK ENIGMA

Charles Darwin was obsessed with domestic pigeons. He thought they held the secrets of selection in their beaks.

Free from the bonds of natural selection, the 350-plus breeds of domestic pigeons have beaks of all shapes and sizes within a single species (Columba livia).

The most striking are beaks so short that they sometimes prevent parents from feeding their own young.

Centuries of interbreeding taught early pigeon fanciers that beak length was likely regulated by just a few heritable factors.

Yet modern geneticists have failed to solve Darwin’s mystery by pinpointing the molecular machinery controlling short beaks – until now.

The study was led by Elena Boer, who completed the research as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Utah School of Biological Sciences.

‘Some of the most striking characteristics of Robinow syndrome are the facial features, which include a broad, prominent forehead and a short, wide nose and mouth, and are reminiscent of the short-beak phenotype in pigeons,’ she said.

‘It makes sense from a developmental standpoint, because we know that the ROR2 signaling pathway plays an important role in vertebrate craniofacial development.’

Charles Darwin was obsessed with domestic pigeons and bred them in his garden.

They provided crucial evidence for his theory that changed the world – evolution by natural selection.

Fancy pigeon breeders have created hundreds of varieties that look dramatically different to wild pigeons – but they all come from one species, Columba livia.

The most striking are beaks so short that they sometimes prevent parents from feeding their own young.

The Natural History Museum explains: ‘Darwin was fascinated by how one species could be manipulated to such extremes.

‘He used this as an analogy – if breeders can artificially manipulate the way a single species looks in captivity, perhaps the environment can manipulate all species naturally in the wild.’

Yet modern geneticists have failed to solve Darwin’s mystery by pinpointing the molecular machinery controlling short beaks – until now.

Charles Darwin (pictured) owned pigeons, and they provided crucial evidence for his theory that changed the world – evolution by natural selection

For the study, the researchers bred two pigeons with short and medium beaks – the male was a Racing Homer, a bird bred for speed with a beak length similar to the ancestral rock pigeon, with a medium beak.

The female was an Old German Owl, a fancy pigeon breed that has a little, squat beak.

The short- and medium-beaked parents produced an initial brood of children with intermediate-length beaks. This brood was dubbed ‘F1’.

When the biologists mated the F1 birds with one another, the resulting grandchildren (‘F2’) had beaks ranging from big to little, and all sizes in between.

To quantify the variation, Boer measured beak size and shape in the 145 F2 individuals using micro-CT scans generated at the University of Utah Preclinical Imaging Core Facility.

‘The cool thing about this method is that it allows us to look at size and shape of the entire skull, and it turns out that it’s not just beak length that differs – the braincase changes shape at the same time,’ Boer said.

Pictured, medium or long beak pigeon breeds, from left to right – West of England, Cauchois, Scandaroon, Show King

Pictured, short beak pigeon breeds, from left to right – English Short Face Tumbler, African Owl, Oriental Frill, Budapest Tumbler. The short-beak birds all had the same ROR2 mutation

‘These analyses demonstrated that beak variation within the F2 population was due to actual differences in beak length and not variation in overall skull or body size.’

Next, the researchers compared the pigeons’ genomes. First, using a technique called quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, they identified DNA sequence variants scattered throughout the genome, and then looked to see if those mutations appeared in the F2 grandkids’ chromosomes.

‘The grandkids with small beaks had the same piece of chromosome as their grandparent with the small beak, which told us that piece of chromosome has something to do with small beaks,’ said Shapiro.

‘And it was on the sex chromosome, which classical genetic experiments had suggested, so we got excited.’

High resolution scans of the grandchildren of the Racing Homer and German Owl cross. The animation shows the variety of beak lengths from shortest to longest

The team then compared the entire genome sequences of many different pigeon breeds – 56 pigeons from 31 short-beaked breeds and 121 pigeons from 58 medium- or long-beaked breeds.

The analysis showed that all individuals with small beaks had the same DNA sequence in an area of the genome that contains the ROR2 gene.

‘The fact that we got the same strong signal from two independent approaches was really exciting and provided an additional level of evidence that the ROR2 locus is involved,’ said Boer.

The authors speculate that the short-beak mutation causes the ROR2 protein to fold in a new way, but the team plans to do functional experiments to figure out how the mutation impacts craniofacial development.

The paper has been published in the journal Current Biology.

CHARLES DARWIN: THE BRITISH NATURALIST WHO INTRODUCED THE IDEA OF NATURAL SELECTION

Pictured: Naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882)

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, the fifth of six children of wealthy and well-connected parents.

One of his grandfathers was Erasmus Darwin, a doctor whose book ‘Zoonomia’ had set out a radical and highly controversial idea, that one species could ‘transmute’ into another. Transmutation is what evolution was then known as.

In 1825, Charles Darwin studied at Edinburgh University, one of the best places in Britain to study science.

It attracted free thinkers with radical opinions including, among other things, theories of transmutation.

Darwin trained to be a clergyman in Cambridge in 1827 after abandoning his plans to become a doctor, but continued his passion for biology.

In 1831, Charles’ tutor recommended he go on a voyage around the world on HMS Beagle.

Over the next five years Darwin travelled five continents collecting samples and specimens while investigating the local geology.

With long periods of nothing to do but reflect and read, he studied Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, which had a profound impact.

The trip also began a life of illness after he suffered terrible sea sickness.

In 1835, HMS Beagle made a five-week stop at the Galapágos Islands, 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador.

There, he studied finches, tortoises and mockingbirds although not in enough detail to come to any great conclusions.

But he was beginning to accumulate observations which were fast building up.

On returning home in 1838, Darwin showed his specimens to fellow biologists and began writing up his travels.

It was then that he started to see how ‘transmutation’ happened.

He found that animals more suited to their environment survived longer and have more young.

Evolution occurred by a process he called ‘Natural Selection’ although he struggled with the idea because it contradicted his Christian world view.

Having experienced his grandfather being ostracised for his theories, Darwin collected more evidence, while documenting his travels, until 1851.

He decided to publish his theory after he began to suffer long bouts of sickness.

Some historians suggest that he had contracted a tropical illness while others felt that his symptoms were largely psychosomatic, brought on by anxiety.

In 1858, Darwin received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, an admirer of Darwin’s from reading about his Beagle Voyage.

Darwin was criticised by the Church and some of the press as people were shaken by the idea that humans descended from apes

Wallace arrived at the theory of natural selection independently and wanted Darwin’s advice on how to publish.

In 1858, Darwin finally went public giving Wallace some credit for the idea.

Darwin’s ideas were presented to Britain’s leading Natural History body, the Linnean Society.

In 1859, he published his theory on evolution. It would become one of the most important books ever written.

Darwin drew fierce criticism from the Church and some of the press. Many people were shaken by the book’s key implication that human beings descended from apes, although Darwin only hinted at it.

In 1862, Darwin wrote a warning about close relatives having children, he was already worried about his own marriage, having married his cousin Emma and lost three of their children and nursed others through illness.

Darwin knew that orchids were less healthy when they self-fertilised and worried that inbreeding within his own family may have caused problems.

He worked until his death in 1882. Realising that his powers were fading, he described his local graveyard as ‘the sweetest place on Earth’.

He was buried at Westminster Abbey.

Source: Read Full Article