Shortly after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Maj. Gen. Leslie R. Groves of the U.S. Army, who directed the making of the weapons, told Congress that succumbing to their radiation was “a very pleasant way to die.”

His aide in misinforming America was William L. Laurence, a science reporter for The New York Times. At the general’s invitation, the writer entered a maze of secret cities in Tennessee, Washington and New Mexico. His exclusive reports on the Manhattan Project, when released after the Hiroshima bombing, helped shape postwar opinion on the bomb and atomic energy.

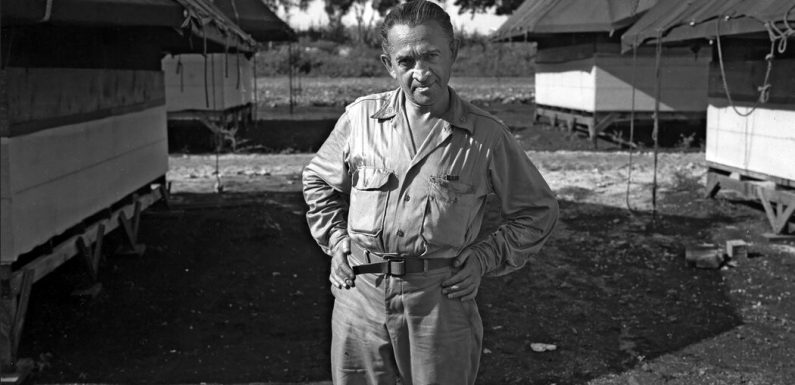

Before the war, Mr. Laurence’s science reporting won him a Pulitzer. Working with and effectively for the War Department during the bomb project, he witnessed the test explosion of the world’s first nuclear device and flew on the Nagasaki bombing run. He won his second Pulitzer for his firsthand account of the atomic strike as well as subsequent articles on the bomb’s making and significance. Colleagues called him Atomic Bill.

Now, a pair of books, one recently published, one forthcoming, tell how the superstar became not only an apologist for the American military but also a serial defier of journalism’s mores. He flourished during a freewheeling, rough-and-tumble era both as a Times newsman and, it turns out, a bold accumulator of outside pay from the government agencies he covered.

By today’s standards, to get the scoop of the century, Mr. Laurence and The Times engaged in a rash of troubling deals and alliances. “Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States,” published in April, tells how Mr. Laurence came to promote Washington’s official line.

He was “willingly complicit in the government’s propaganda project,” said Alex Wellerstein, the book’s author and a nuclear historian at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J.

Washington’s choice of Mr. Laurence was both smart and surprising, Dr. Wellerstein said in an interview. He noted that the science reporter was then a rising star at one of the world’s most respected newspapers. But he also described Mr. Laurence as a man of gaudy ties and ill-fitting suits, “a bizarre figure” who was no stranger to clichés and questionable claims. His reporting, it turns out, also teemed with financial conflicts.

Vincent Kiernan, author of a Laurence biography to be published next year by Cornell University Press, shows that, during the war, Mr. Laurence augmented his Times salary with supplementary pay from not only the Manhattan Project but also the Army surgeon general and, toward the end of his Times career, from Robert Moses, the master builder of New York City.

The newsman, Dr. Kiernan said in an interview, “made decisions based on what was best for him, not necessarily on what was in the best interest of the public. He was primarily interested in building his own brand.” To that end, Dr. Kiernan added, over 34 years at The Times, “he had a track record of ethically fraught behavior.”

Mr. Laurence died in 1977 at age 89. The Times began his obituary on Page 1 and said he had conceived of his beat as the universe.

Dr. Kiernan, dean of professional studies at Catholic University and a former reporter himself, has long studied the ties between science journalists and their sources. For his Laurence book, he combed a number of archives, including those of The Times.

The newspaper seems to have been aware of Mr. Laurence’s financial conflicts, at least in outline. It tightened its ethical guidelines repeatedly in the decades following his retirement, often in reaction to scandals. A current company handbook spells them out in considerable detail, and it seems clear that Mr. Laurence’s actions back then would have crossed a number of red lines today.

On the Payroll of The Times

Mr. Laurence was born in 1888 to Lipman and Sarah Siew in an area of Lithuania that was then part of Czarist Russia. He was a short man with a flattened nose — crushed, he said, by the butt of a Cossack rifle in his youth.

A quick learner and skilled at languages, he fled as a teenager after the revolution of 1905, landed in the United States, and recast himself as William Leonard Laurence.

He ended up in Cambridge, Mass., where he studied drama, literature and philosophy at Harvard. Recently, the school said it had awarded him no diploma, despite reports to the contrary. Mr. Laurence served in World War I and, in the 1920s, began his newspapering at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, today considered a pioneer of yellow journalism.

In 1930, Mr. Laurence joined The Times in what was then a new role for him as well as the newspaper — a reporter who focused exclusively on science. Whether he knew much about the daunting field is unclear. What animated him was an urge to write exclusives, to be first, to get his story onto Page 1. A Times editor, no doubt exaggerating, once told a federal official that Mr. Laurence would “commit suicide” if scooped on one of his big stories.

If glory beckoned, the pay did not. “Newspapermen were exploited,” Mr. Laurence told an oral historian at Columbia University late in life. “They worked unconscionable hours.” He said reporters at The World and The Times put in roughly 70 hours a week and “had no redress” if a day off was suddenly canceled. “They got no overtime.”

Mr. Laurence felt not only exploited but also drawn to status and power. He and his wife, Florence, who never had children, liked to point out publicly that they walked their little dachshund on Sutton Place in Manhattan. Taking up residence in the East Side enclave was a small step in what would become a long social climb.

On the Payroll of the Healer

Mr. Laurence’s first articles in The Times coincided with the Great Depression and regularly told of near miracles. He trumpeted would-be cures for cancer, the common cold and even the brevity of human life. Dwarfs could grow tall. In 1934, a Page 1 story declared that new drugs would not only mend nature’s errors in the making of human beings but also yield superhuman minds and bodies.

Hitler’s invasions in the late 1930s and early 1940s — the start of another great war — shook not only the world but also Mr. Laurence personally as Nazi troops entered his home village and killed many of its Jewish inhabitants, including his brother, sister and mother.

He threw himself into wartime coverage. He told of new ways to heal infections and prevent shock among the wounded. “Research Workers Are Bent Upon Winning the War,” read one headline.

By early 1944, American troops were taking Pacific islands, invading Italy and preparing to open a wide front in Europe. Maj. Gen. Norman T. Kirk, the Army surgeon general, was eager to reassure families that their sons and daughters were getting the best possible care. He hired science writers to advise his office and compose news releases on the accomplishments of the medical corps.

Mr. Laurence joined in. Dr. Kiernan said federal records showed that he began his Army employment in April 1944, and that the surgeon general had asked The Times for permission to put the newsman onto the supplemental job. And the biographer shared with The Times a document showing that the office of the surgeon general had addressed its aid request to the newspaper’s editor.

The code of ethics promulgated by the Society of Professional Journalists at the time frowned on such financial conflicts. So did The Associated Press, the world’s largest news agency, Dr. Kiernan said. Yet science reporters from places like The Chicago Daily News took on such work, as did a science writer for the American Medical Association. Wartime service of this sort was at times commended as patriotic.

On the Payroll of the Bomb Maker

Early in his Times career, Mr. Laurence described not only medical wonders but also, in a series of prescient reports, the unlocking of the atom. It began in 1932 as scientists split the atomic nucleus for the first time and started investigating how to release bursts of nuclear energy.

Like other journalists, Mr. Laurence obeyed wartime bans on the description of troop movements, presidential meetings and military secrets. In December 1943 and August 1944, he sought permission from the Office of Censorship to publish articles on how uranium could fuel atomic detonations. Both times he was denied.

Washington feared that the public release of such information would encourage Nazi Germany to build a bomb. The biggest secret of all — that atomic bombs could be constructed — was impossible to hide once the weapons had been used in war. Dr. Wellerstein, the historian, said Washington’s strategy for that day was to release just enough information to satisfy public curiosity.

As the bomb neared completion, General Groves visited The Times and recruited Mr. Laurence for the writing job. In his book, “Now It Can Be Told,” he said the arrangement called for Mr. Laurence to be paid by both the Manhattan Project and The Times. Meyer Berger, in his authorized history of the newspaper, from 1851-1951, confirmed the pay arrangement and reported that the managing editor and Arthur Hays Sulzberger, the publisher, “were proud” that a Times man had been picked “to perform an important war service.”

In April 1945, the reporter began his tour of secret cities — Oak Ridge, Tenn.; Hanford, Wash.; and Los Alamos in the wilds of New Mexico. There, ringed by armed guards and military censors, thousands of experts toiled on the weapon and prepared for its experimental debut in the nearby desert.

On July 16, in predawn darkness, Mr. Laurence witnessed the birth of the atomic age. In theory, an observer on Mars could have seen the blinding flash.

Mr. Laurence aided the War Department’s disinformation campaign around the test. The news release he wrote up for the department reported falsely that an ammunition depot had exploded. Federal agents, Dr. Wellerstein notes, scanned the local newspapers and concluded that the surrounding townspeople had believed the cover story.

According to the newsman, as well as General Groves, The Times devised its own cover story to hint at why Mr. Laurence had disappeared from the newsroom. A story out of London carried his byline.

Dr. Wellerstein found the archives of the Manhattan Project to be rich not only in Mr. Laurence’s writings but also in the cuts, edits and rebuffs of his military editors.

For instance, Mr. Laurence wrote a draft statement in which President Harry S. Truman was to announce the atomic bombing of Japan. The typescript ran to 17 pages. Bringing the “Cosmic Fire” down to Earth, the reporter wrote, had required American “genius, ingenuity, courage, initiative and farsightedness on a scale never even remotely matched before.”

It went nowhere, Dr. Wellerstein reports. James B. Conant, the president of Harvard and a bomb-project consultant, faulted the draft as “highly exaggerated.”

Mr. Laurence then focused on writing science stories. Dozens were to be distributed freely to the American press corps after the atomic bombings as a way to flood journalists with a superabundance of unclassified material.

His list of nearly 30 articles included one in which the unlocked atom was to free humanity from the planet’s “gravitational bonds.” Midlevel officials vetoed the story, as did General Groves. Eventually, the War Department distributed a handful of his reports on such narrow topics as purifying uranium fuel for the Hiroshima bomb and making plutonium fuel for the Nagasaki bomb.

On Aug. 6, the day of the Hiroshima bombing, The Times revealed that Mr. Laurence had “obtained leave” from the newspaper to learn about the new weapon.

Dr. Wellerstein says Mr. Laurence’s reports written for the War Department did in fact dominate the nation’s early news coverage. Many newspapers, he writes, “happily reprinted what was essentially propaganda produced and sanctioned by the U.S. government.”

Glaringly, Washington downplayed how atomic radiation could maim and kill. It apparently saw news of agonizing deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki as eroding America’s moral high ground and arousing public sympathy for the defeated Japanese.

Dutifully, Mr. Laurence echoed the official line. Weeks after the Hiroshima bombing, his front-page article of Sept. 12, 1945, said the destructive force of the atomic blast, not its radiation, had devastated the city and its inhabitants. The scientific finding, Mr. Laurence claimed misleadingly, refuted “Japanese propaganda” that the bomb’s invisible rays had produced thousands of victims.

In contrast, the book “Hiroshima,” by John Hersey of The New Yorker, published a year later, told of unimaginable suffering from radiation poisoning.

Over the decades, experts clashed vigorously on Mr. Laurence’s atomic reporting. Beverly Deepe Keever, a war correspondent in Vietnam who later taught journalism, denounced the “double-pay arrangement” between The Times and the federal government as a brazen conflict of interest.

Dr. Wellerstein describes Mr. Laurence as unquestionably biased. The Times reporter used his privileged access “to push positions that were favorable to the government,” he writes in his book, as well as to ignore “many aspects of the narrative that made Manhattan Project officials uncomfortable, like the discussion of civilian casualties or radiation injuries.”

Defenders of Mr. Laurence fault his critics for using modern standards to judge history as well as failing to consider the wartime context. Arthur Gelb, who died in 2014, was a former managing editor of The Times who joined paper in 1944. He knew Mr. Laurence and saw him as courageous.

“We were fighting a war for survival,” Mr. Gelb told an interviewer in 2009. “No one thought of Laurence as a villain. That’s ridiculous. He was a hero.”

Michael S. Sweeney, author of “Secrets of Victory,” a book on World War II censorship, argues that Mr. Laurence was no different from thousands of other journalists who were loyal to the American war effort as the country sought to defeat the Axis powers and their allies.

In an interview, Dr. Sweeney said The Times and Mr. Laurence “did the right thing” by making themselves “as supportive of the war as anyone else.”

But coverage of the wartime bomb project, it turns out, would not be Mr. Laurence’s last brush with ethical conflict and controversy.

On the Payroll of the Power Broker

Journalistic prominence turned Mr. Laurence and his wife into social lions. They now lived on the Upper East Side at One Gracie Square, overlooking Carl Schurz Park and Gracie Mansion, the mayor’s residence. Mrs. Laurence organized concerts in the park and held receptions at their home.

In 1956, Mr. Laurence had been promoted to science editor of The Times. He moved from the newsroom to the 10th floor, its ceilings vaulted and windows made of stained glass. It was a hushed warren of scholarship and civility. There, Mr. Laurence wrote a Sunday column, directed the paper’s science coverage and served as a member of the editorial board, writing on science and related topics.

Mr. Moses, the city builder, was president of the World’s Fair, set to open in New York City in 1964. It was to be the triumphal culmination of his long career. He drew up plans for big new buildings, promoted them lavishly, and hired Mr. Laurence to lead the fair’s science committee. The aim was to create a global sensation that outlived the fair.

In 1960, Mr. Laurence’s committee, in a proposal to the federal government, said the fair’s science center “should be the finest of its kind, fully commensurate with the greatness of America.” The cost of the complex was put at $30 million, or today more than $270 million. The Times article on the plan noted Mr. Laurence’s role as the committee’s head.

For producing the federal report, Dr. Kiernan said, the World’s Fair paid Mr. Laurence and his team $30,000, or today more than $275,000.

The inauguration of President John F. Kennedy in January 1961 raised the pace of preparations for the fair, as well as Mr. Laurence’s profile. The president broke ground for the fair’s U.S. pavilion in 1962. That same year, Mr. and Mrs. Laurence joined the first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, as advisers to the newly formed American Symphony Orchestra, based in New York.

Even so, work on the science center slowed as a rival group of city planners called for a museum of science to be built in Manhattan. They argued that, after the fair closed, the site in Queens would be too remote to draw the crowds needed to support a major institution.

In April 1963, Mr. Laurence wrote a Times editorial, “A Hall of Science.” As is the custom, it was unsigned and meant to represent the opinion of the newspaper as an institution, not the writer.

It described the Queens project as “a potent weapon in the battle for the minds of men” and called on the city to contribute $3.5 million to its construction — in today’s dollars, more than $30 million. The plan, it said, “deserves the whole-hearted support of all who are interested in making New York the cultural as well as the political, financial and industrial center of the free world.”

The editorial ran Wednesday, April 24, 1963. The next day, Mr. Laurence, as chairman of the fair’s science committee, appeared before the city’s Board of Estimate to promote the project. On Friday, The Times reported that he had testified on behalf of the Queens plan and that, after a two-hour debate, the board had voted unanimously to approve the $3.5 million appropriation.

The episode was a serious breach that The Times grew to regret, according to Dr. Kiernan, who learned of the reaction from the archival papers of John B. Oakes, the editor of the editorial page at the time. He was out of town when the editorial ran “and, when he came back, there was hell to pay,” Dr. Kiernan said.

Mr. Laurence was ordered to take no more payments for his work on the World’s Fair project and to write no more editorials on the costly endeavor. Dr. Kiernan added that the journalistic fallout appears to have contributed to Mr. Laurence’s retirement the next year — on New Year’s Day, 1964. Then 75, he went to work full time for Mr. Moses.

“There’s no evidence that Laurence understood the ethical issue,” Dr. Kiernan said. “It was, “Hey, I did it on my own time.’”

In retirement, Mr. Laurence’s star dimmed. The society pages no longer took notice of him and his wife. They moved to Majorca, a Spanish isle in the Mediterranean. Dr. Kiernan said Mr. Laurence kept up a correspondence with Mr. Moses. The two men shared not only a birth year, 1888, but also, he said, “a sense of affection.”

Money remained an issue.

In 1967, Mr. Laurence wrote The Times to say it had shortchanged him during his time with the Manhattan Project and owed him $2,125 in back pay, or today more than $30,000. The paper, he said, “should in all fairness reimburse me together with the proper amount of legal interest.” It demurred.

Source: Read Full Article