How T.Rex delivered its bone crushing bites: King of the dinosaurs maintained a stiff lower jaw to keep struggling prey in place, study reveals

- New research addresses ‘longstanding mystery’ on the anatomy of the T.Rex jaw

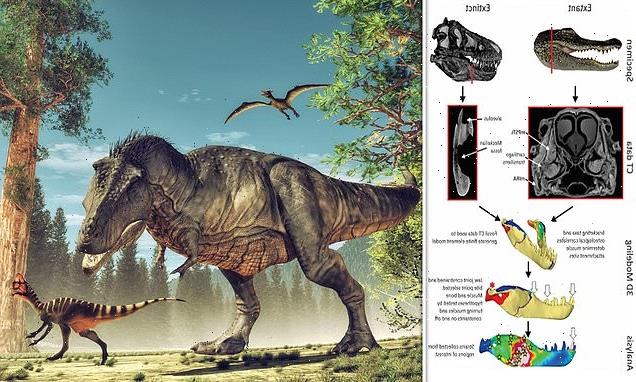

- US researchers used CT scans of dinosaur fossils and modern-day specimens

- T.Rex would crunch down and ingest bones of its prey, previous evidence shows

Tyrannosaurus rex (T.Rex) was only able to crunch the bone of its unfortunate prey thanks to its stiff lower jaws, a new study shows.

Perhaps the most fearsome of all the dinosaurs, T.Rex chomped through bone by keeping a joint in their lower jaw steady like an alligator, it reveals.

Scientists had previously assumed T.Rex had a flexible jaw like a snake to keep struggling prey in their jaws, but the new analysis shows the lower jaw was kept level and sturdy.

The experts used computed tomography (CT) scans of dinosaur fossils and modern reptiles to build a detailed 3D model of the T.Rex jaw.

Tyrannosaurus rex (T.Rex) would crunch down and ingest the bones of its prey, previous fossil evidence suggests. Now, new research addresses longstanding mystery on the anatomy of the Tyrannosaurus rex jaw

WHAT WAS T. REX?

Tyrannosaurs rex was a species of bird-like, meat-eating dinosaur.

It lived between 68–66 million years ago in what is now the western side of North America.

They could reach up to 40 feet (12 metres) long and 12 feet (4 metres) tall.

More than 50 fossilised specimens of T. rex have been collected to date.

The monstrous animal had one of the strongest bites in the animal kingdom.

An artist’s impression of T. rex

‘We discovered that these joints likely were not flexible at all, as dinosaurs like T.Rex possess specialised bones that cross the joint to stiffen the lower jaw,’ said study author John Fortner at the University of Missouri.

The research sheds new light on a conundrum – or ‘biomechanical paradox’ as the team put it.

It’s already known T.Rex could bite hard enough to shatter the bones of its prey, but how it accomplished this feat without breaking its own skull bones has perplexed paleontologists.

Increasingly now, researchers argue that its skull was stiff much like the skulls of hyenas and crocodiles, and not flexible like snakes and birds as some scientists previously thought.

Dinosaurs had a joint in the middle of their lower jaws, called the intramandibular joint, which is also present in modern-day reptiles.

Previous research has suggested this joint was flexible, like it is in snakes and freaky-looking monitor lizards, helping carnivorous dinosaurs to keep struggling prey in their jaws.

However, it has been unclear whether the jaws were flexible at all, or how they could be strong enough to bite through and ingest bone, which Tyrannosaurus did regularly, according to fossil evidence.

The researchers used CT scans of dinosaur fossils and modern-day specimens, including the crocodile, to create a 3D computer model of a dinosaur jaw and identify where muscles attach to bone.

They then used the model to simulate muscle forces under different biting scenarios.

Unlike previous models, their simulations include bone, tendons and specialised muscles that wrap around the mandible (the lower jaw).

‘We are modelling dinosaur jaws in a way that simply has not been done before,’ said Fortner.

‘We are the first to generate a 3D model of a dinosaur mandible which incorporates not only an intramandibular joint, but also simulates the soft tissues within and around the jaw.’

To determine whether the intramandibular joint could maintain flexibility under forces required to crunch through bone, the team ran simulations to calculate the strains that would occur at various points depending on where the jaw hinged.

The results suggest bone running along the inside of the jaw called the prearticular acted as a strain sink to counteract bending at the intramandibular joint, keeping the lower jaw stiff.

Previous research has suggested this joint was flexible, like it is in monitor lizards (pictured) and snakes today, helping carnivorous dinosaurs to keep struggling prey in their jaws. In the wild, the almost dinosaur-like monitor lizard eats reptiles, small mammals, insects, eggs, birds and more

The team plans to apply their modelling approach to other dinosaur species to further shine some light on the biting mechanics among dinosaurs.

The results, which are being presented online this week, could even help researchers better understand today’s creatures.

‘Because dinosaur mandibles are actually built so much like living reptiles, we can use the anatomy of living reptiles to inform how we construct our mandible models,’ said Fortner.

‘In turn, the discoveries we make about T.Rex’s mandible can provide more clarity on the diversity of feeding function in today’s reptiles like crocodilians and birds.’

The study is being presented at the American Association for Anatomy annual meeting during the Experimental Biology (EB) 2021 meeting, held virtually from April 27 to 30.

The findings come shortly after a study published last week found that despite their brutal feeding habits, T.Rex had only a moderate walking speed.

Scientists in the Netherlands developed a new method to estimate the preferred walking speed of T. Rex, based on analysis of a preserved specimen called Trix, currently on display at Museum Naturalis in Leiden, Netherlands.

They revealed T. Rex enjoyed a ‘leisurely’ stroll at just 2.8 miles per hour (4.6km per hour) – a rate similar to the natural walking speed of emus, elephants, horses and humans and lower than previous estimates.

T.Rex just got even scarier! King of the dinosaurs may have hunted in PACKS just like wolves

Pictured: the skill of a T.Rex found two miles north of the so-called ‘Rainbows and Unicorns quarry’ in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

Tyrannosaurus rex may not have been a solitary predator, but instead hunted its prey in packs, just like wolves, a 2021 study suggested.

Palaeontologists have been studying a T.Rex mass death site found back in 2014 in the so-called Rainbows and Unicorns quarry in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.

Analysis of T.Rex fossil bones revealed that members of the species died and were buried together.

The notion that tyrannosaurs might have been social carnivores was first mooted some two decades ago, when more than a dozen of the dinosaurs were found buried together at a dig site in Alberta, Canada.

A second mass grave site was subsequently found in Montana – and the Rainbows and Unicorns quarry assemblage makes for the third found to date.

‘Going that next step to understand behaviour and how animals behave requires really amazing evidence,’ said Denver Museum of Nature & Science’s curator of dinosaurs, Joseph Sertich.

‘I think that this site – the spectacular collection of tyrannosaurs but also the other assembled pieces of evidence – pushes us to the point where we can show some evidence for behaviour.’

Despite the mounting evidence, many experts have contested the idea, arguing that dinosaurs simply did not have the brainpower needed for complex social interaction.

Read more: T.Rex may have hunted in PACKS just like wolves, study reveals

Source: Read Full Article