Vegan ‘spider silk’ developed that is as strong as many common plastics and could provide a sustainable alternative material for single-use products

- Researchers at Cambridge have created a polymer film inspired by a spider web

- Their new energy-efficient method uses a by-product of soybean oil production

- The plant-based film is being tested in food packaging like sandwich containers

A new vegan sustainable film could replace single-use plastics in many consumer products, scientists say.

The film, created at the University of Cambridge, is inspired by spider silk, one of the strongest materials known to nature.

It has the strength of human-made synthetic polymers in plastic bags and film wraps, but fully decomposes naturally, without harming the environment.

The new product will be commercialised by Xampla, a University of Cambridge spin-out company developing replacements for single-use plastic and microplastics.

Xampla will introduce a range of single-use sachets and capsules later this year, which can replace the plastic used in everyday products like dishwasher tablets and laundry detergent capsules – many of which still come in individual plastic wrappers.

The firm is also testing the plant-based film in food packaging like sandwich containers and salad boxes.

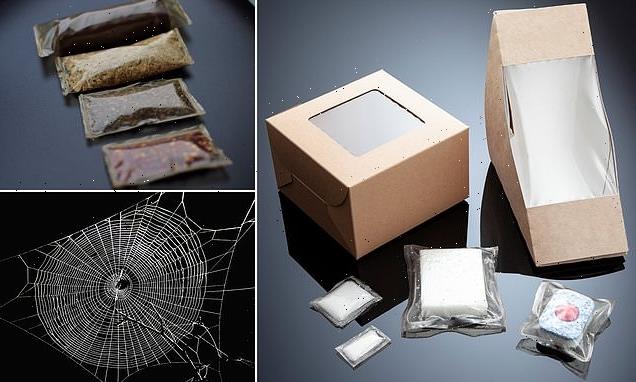

The film, developed by Cambridge spin-out company Xampla, is pictured here in food packaging, dishwasher tablets and laundry detergent capsules

WHY ARE SPIDER WEBS SO STRONG?

The strength of a biological material like spider silk lies in the configuration of structural proteins, which have small clusters of weak hydrogen bonds that work cooperatively to resist force and dissipate energy.

This structure makes the lightweight natural material as strong as steel, even though the ‘glue’ of hydrogen bonds that hold spider silk together at the molecular level is 100 to 1,000 times weaker than the powerful glue of steel’s metallic bonds.

Source: MIT

It’s also working on developing edible films, which can be used for applications such as oral delivery of drugs.

Non-fading ‘structural’ colour can also be added to the polymer, and it can also be used to make water-resistant coatings.

The production method can be bumped up to industrial scale, the experts claim.

‘Other researchers have been working directly with silk materials as a plastic replacement, but they’re still an animal product,’ said study author Rodriguez Garcia at the University of Cambridge.

‘In a way we’ve come up with “vegan spider silk” – we’ve created the same material without the spider.’

The material is able to be composted at home, whereas other types of bioplastics require industrial composting facilities to degrade.

It also requires no chemical modifications to its natural building blocks, so that it can safely degrade in most natural environments.

The material was created using a new approach for assembling plant proteins into materials that mimic silk on a molecular level.

Spiders are master builders, expertly weaving strands of silk into intricate webs that serve as the spider’s home and hunting ground.

Xampla will introduce a range of single-use sachets this year for holding food ingredients (pictured) and cleaning products

Spider webs are as strong as steel, even though the ‘glue’ of hydrogen bonds that hold spider silk together at the molecular level is 100 to 1,000 times weaker than the powerful glue of steel’s metallic bonds.

The researchers became interested in why materials like spider silk are so strong when they have such weak molecular bonds.

‘We found that one of the key features that gives spider silk its strength is the hydrogen bonds are arranged regularly in space and at a very high density,’ said study author Professor Tuomas Knowles at Cambridge.

The team began looking at how to replicate this regular self-assembly in other proteins.

Researchers created the film by mimicking the properties of spider silk, one of the strongest materials in nature

POLYMERS AND MONOMERS

Most plastics are made of polymers, chains of hydrogen and carbon, obtained from petroleum products like crude oil.

Polymers are composed of shorter strands called monomers.

Many plastics can’t be reused due to additives mixed in with them, making them difficult to dispose of because the monomers can’t separate from them.

Any replacement for plastic requires another polymer.

The team replicated the structures found on spider silk by using soy protein isolate (SPI), which is readily available as a by-product of soybean oil production.

Proteins have a propensity for molecular self-organisation and self-assembly.

‘Because all proteins are made of polypeptide chains, under the right conditions we can cause plant proteins to self-assemble just like spider silk,’ said Knowles.

‘In a spider, the silk protein is dissolved in an aqueous solution, which then assembles into an immensely strong fibre through a spinning process which requires very little energy.’

However, plant proteins such as SPI are poorly soluble in water, making it hard to control their self-assembly into ordered structures.

So the new technique uses an environmentally friendly mixture of acetic acid and water, combined with ultrasonication and high temperatures, to improve the solubility of the SPI.

This method produces protein structures with enhanced ‘inter-molecular interactions’ guided by its unique and ultra-strong hydrogen bond formation.

In a second step the solvent is removed, which results in a water-insoluble film.

The researchers used soy protein isolate (SPI) as their test plant protein, since it is readily available as a by-product of soybean oil product

The material has a performance equivalent to high performance engineering plastics such as low-density polyethylene – one of the most widely produced plastics in the world.

Polyethylene, also known as #1 plastic, is used in a huge variety of products from plastics bags, plastic milk jugs and shampoo bottles to corrosion-resistant piping, wood-plastic composite lumber and plastic furniture.

The polymer is found in about a third of all plastics produced, and has a global value of about $200 billion (£142 billion) annually.

For many years, Professor Knowles had actually been researching the behaviour of proteins for many years – but in relation to degenerative disease.

Much of his research has been focused on what happens when proteins misfold or ‘misbehave’, and how this relates primarily to dementia.

‘We normally investigate how functional protein interactions allow us to stay healthy and how irregular interactions are implicated in Alzheimer’s disease,’ said Knowles.

‘It was a surprise to find our research could also address a big problem in sustainability – that of plastic pollution.’

The results are reported in the journal Nature Communications.

Just 20 firms produce 55% of the world’s plastic waste – with ExxonMobil topping the list, contributing 5.9MILLION tonnes per year, report reveals

Just 20 firms produce 55 per cent of ‘throwaway’ single-use plastic that ends up as waste worldwide, a May 2021 report revealed.

Texan oil company ExxonMobil tops the list of polymer producers generating single-use plastic waste, having contributed 5.9 million metric tonnes in 2019 – equivalent to the weight of 5,700 blue whales.

ExxonMobil was closely followed by Michigan chemicals company Dow and China oil company Sinopec, which contributed 5.6 and 5.3 million tonnes in 2019, respectively.

These three companies together account for 16 per cent of global single-use plastic waste, according to the newly-published Plastic Waste Makers index.

At 44 kg, the UK is also the fourth largest producer of single-use plastic waste per capita globally, the report found.

Read more: Just 20 firms produce 55% of the world’s plastic waste, report reveals

Source: Read Full Article