“Some time ago… there was an Ojibwe man who got a little sick and wandered West.” So begins Lyle Mitchell Corbine, Jr.’s bleak and disquietingly self-loathing “Wild Indian,” which adapts that folkloric tone into the airless language of a contemporary serial-killer drama. We learn that the Ojibwe man was a little sicker than his legend suggested.

When we meet Makwa, he’s as a troubled pre-teen in the 1980s, when he lives in an oppressively gray stretch of middle American nowhere with abusive parents. Played in these formative years by a remarkable young actor named Phoenix Wilson — whose punctured tire of a voice sounds like on the brink of crying over a sense of dispossession he doesn’t have words to describe — Makwa is held in the grip of an anger that seems much older than he is.

The priest at the local Catholic school preaches about Cain’s sacrifice and the poison of a tortured spirit, but Makwa doesn’t appear to understand how to engage with the horrors that he inherited, let alone why that responsibility should fall to him. (“Wild Indian” is deliberately oblique about the displacement of the Ojibwe, as Corbine renders that colonial residue less as a series of events than the murky water in which his characters swim.)

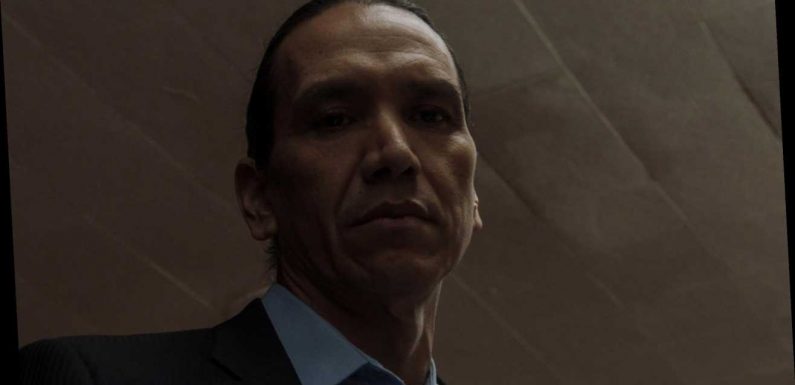

Toward the end of another grim afternoon, walking through the woods with his only friend Ted-O, Makwa insists that he doesn’t want to go home. Instead, he picks up the rifle they nicked from Ted-O’s dad and unemotionally murders a classmate who happens to be walking nearby. He isn’t caught, and his friend never tells. As the film jumps into the present, Ted-O (Chaske Spencer) is now a heavily tatted heroin dealer who’s spent most of his adult life in prison and Makwa (Michael Greyeyes) is a mid-level executive at a generic California business where he reports to an antsy boss (Jesse Eisenberg).

He goes by “Michael Peterson” now, and lives with his white wife (Kate Bosworth), their young son Francis, and another baby on the way. He prays to Jesus in moments of quiet desolation and doesn’t let anyone wear shoes in the house. But eager as Makwa is to snuff out the last embers of his Ojibwe past, the horror in him refuses to go silent. The residual violence of being separated from one’s heritage — either through force, or by fleeing it — still pounds inside him, and that heartbeat grows louder when Ted-O decides to pay him a visit.

The great shock of “Wild Indian” is Corbine isn’t afraid to paint Makwa as more of a sociopath than a victim. The filmmaker destabilizes that false dichotomy to such a frightening degree that audiences might see him as a simple monster as opposed to an overflowing vessel for centuries of genocidal trauma. Not that one kind of murder excuses another — Makwa’s adoptive savior would tell him to turn the other cheek — but that myopic view reflects the ahistorical convenience that white America depends upon, and that Makwa has come to depend upon as well.

This isn’t subtle; the adult Makwa is introduced while playing golf and licking his lips at the thought of some woman at his company getting fired so he can take her job. Greyeyes embodies the character with a constant and vibrating sense of stone-cold menace; Makwa can’t even remove his Invisalign retainer without radiating Patrick Bateman vibes. He and Eisenberg’s nervous character are a deliciously mismatched pair, and their few banal conversations feel like they could go full Anton Chigurh at the flip of a coin. There’s a flicker of sadistic and power-inverting relish in Makwa’s eyes when he asks his boss about cutting his traditional braid, as though even “Michael” can’t resist the temptation to weaponize white discomfort.

Greyeyes is deeply unnerving as a horror movie in human form, his flat voice and sinewy frame layering serial-killer stereotypes into the fabric of a man who sustains himself through constant suffocation. Self-asphyxiation is difficult to scale over decades, and now Makwa needs to choke the life out of other people to keep his demons at bay. It’s a pathology that Corbine struggles to articulate; a scene in which Makwa strangles a stripper within an inch of her life (for money) wanders into sub-“Dexter” territory, while long stretches of the film’s second half — where Makwa tries to tie loose ends and silence the remnants of his heritage — so giddily embrace serial-killer tropes that it starts to seem as if this is supposed to be fun.

The funereal severity of Corbine’s approach would seem to suggest otherwise. And while Greyeyes’ arresting performance leaves room to wonder if Makwa enjoys this — if he takes a sick pride in disproving the fear that he and Ted-O are the descendants of cowards because “everyone worthwhile died fighting” — the film lacks the oxygen to breathe life into more complicated readings. Compelling as it can be to watch Makwa grow increasingly monstrous, his trajectory is pathological to a degree that dampens the fullness of his character, and blackens the rays of light that threaten to complicate his family life. (Makwa says he wants his kids to be “normal and good,” and the movie is never better than when it allows us to sit with the potential sincerity of such moments.)

Haunted but indivisibly humane, Ted-O provides a knowing contrast to his childhood friend, and Spencer’s performance is filled with all the hard-fought warmth the rest of the film lacks. Brief scenes where he leaves prison and moves in with his sister — or at least into a tent on her lawn — are a complicated reprieve from a movie that spends most of its time spiraling down the same dark hole. “Wild Indian” is sobering and powerful for how Corbine nests personal tragedies inside historical ones, but some of its most lingering sadness can be traced back to his decision to emphasize Ted-O as Makwa’s last remaining drop of Ojibwe blood, and not Makwa as Ted-O’s cross to bear.

Grade: C+

“Wild Indian” premiered in the U.S. Dramatic Competition at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival. It is currently seeking U.S. distribution.

Source: Read Full Article