When someone gets the plum job as the boss, there is usually a honeymoon period that allows the recipient to settle in, place a novelty coffee mug in the executive canteen and position a few family snaps to suggest non-psychopathic traits. For Victoria’s 23rd chief commissioner, Shane Patton, his lasted just over a week.

He took the job in late June last year and by early July the state was plunged into quasi-wartime conditions.

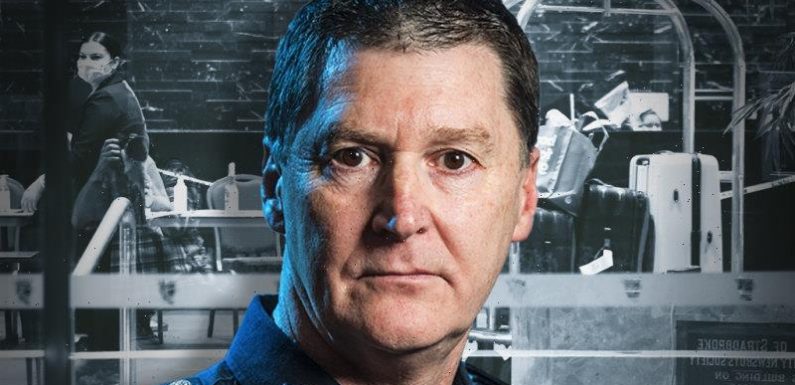

Chief Commissioner Shane Patton.Credit:The Age

A man with the plan to embrace community policing, he had to enforce often unpopular medical regulations alongside criminal ones.

At the time he would have thought WHO was a British rock band, not the World Health Organisation, Lockdown a professional wrestling event and CHO a condiment found in Vietnamese restaurants.

Since then, he has invested a large portion of his workforce in policing COVID restrictions and balancing work-from-home rules for staff not on the front line.

Not the World Health Organisation: the other WHO.Credit:AP

On a bad day, 2300 police are taken from traditional duties to enforce hotel quarantine, patrol borders, grab curfew-breakers and confront illegal demonstrators.

It is work police hate for three reasons: It is boring, it stops them chasing real crooks and often has them enforcing unpopular rules.

No cop wants to tell people to move on from standing outside coffee shops, or demand to see the work permits of people out and about. Recruits at the Police Academy were not taught how to order kids off the monkey bars at the park.

“There is no doubt there has been a significant impact on the members themselves,” says the Chief Commissioner. “And there has been an impact on public confidence in policing but [enforcing the COVID rules] is something we are required to do. We need to do it. This is how we stop it [mass infections].”

When Patton took the top job he announced a clear philosophy of back-to-basics policing, tough on crime, visible police presence and community engagement. It did not, however, include “sending our people to break up fights over toilet paper at the supermarket”.

Some demonstrations have been particularly ugly, with police for the first time using anti-riot weapons that can fire squash ball-like projectiles and capsicum dust-filled rounds.

Victoria Police confront protesters in Victoria Street, North Melbourne, on May 29 for breaching lockdown directives. Credit:Chris Hopkins

Police say some demonstrators arrive with only one plan: to try and fight cops. “Why would you bring two litres of milk to a protest?” asks Patton. (It is a rhetorical question. The reason is to wash eyes stinging from capsicum foam.)

In the aftermath some protesters have used social media to try and identify police at the demonstrations. One posted pictures asking: “I am trying to identify these four individuals in order to report them for assault.” The names of some police photographed were freely shared online.

Responses varied from reasoned to “they actually need a belting when they are off-duty”.

The father of one officer identified says he and his family have been targeted in a campaign of intimidation that required increased security.

Police are now authorised to remove their name tags for demonstration shifts but must display their registered number to be identified if subject to complaint.

Patton says he is disgusted that police “who are just doing their job have been subjected to this rubbish. It can create havoc to members and their families.”

He warns those posting and sharing inflammatory posts face the new offence of “intimidation of a law enforcement officer”, which carries a maximum penalty of 10 years’ jail.

The law states the offence of intimidation of a law enforcement officer or a family member occurs when “the person engages in conduct that could reasonably be expected to arouse apprehension or fear in the victim for the safety of the victim”.

Last week eight people were arrested relating to the posts.

At the beginning police treated COVID-19 as they would any other statewide emergency, such as bushfires and floods, working out of the State Police Operations Centre. Patton says police, like the rest of us, have to learn to deal with the virus long-term.

Which is why he is setting up a specialist COVID Command with a police commander to be appointed in charge of COVID response and a second in charge of hotel quarantine. They will stay in those roles until the end of next year at minimum.

While acknowledging dealing with the virus is “the biggest game in town”, policing is not a one-issue job and Patton wants to roll out a series of changes in the next 12 months. It would be wrong to call them reforms because it is really a case of returning to traditional policing.

Patton doesn’t want local policing controlled from the big end of town. He wants to introduce local safety committees with town hall and virtual meetings where residents tell police of their concerns: “It is for the community to tell us what it needs, not the other way around.”

It may be hoons doing burnouts, street gangs hanging around parks, graffiti or vandalism. Under the plan the public concerns would be loaded into the police computer and uploaded to local patrols’ smart devices, resulting in an immediate response in a policy known as “real-time policing”.

In another move away from one-size-fits-all law enforcement, police will return to schools, but not with an off-the-rack policy: “Each school will be approached so we can provide a program catered for them.”

There will be three elements. Building respect and trust with police, educating students about specific issues or intervention in cases of criminal behaviour. “It may be road safety, sexual consent, drugs or cyber crime, and we may use specialist police from those areas.”

For some reason, for some time, some senior police have tied themselves in knots when it comes to gangs. First we had some say bikie gangs were not an issue, which was, frankly, nonsense.

Then we had others who wouldn’t use the G-word in relation to street gangs for two reasons: the view that giving them a title acted as a recruiting poster for disillusioned youth; and that, because some gangs were ethnically based, it could be seen as racist.

But if you ignore a problem it won’t go away. Patton is straightforward: “Gangs are the hiding place for cowards.

“We need to disrupt before they can escalate. It starts with fights, then knives, machetes, imitation firearms and then real guns.”

Diversion will involve police visiting homes to intervene with young would-be gang members explaining if they don’t change their present path it will end badly.

“If the carrot doesn’t work we will bring out the stick,” says Patton.

This is not just about annoying and potentially dangerous street gangs.

The head of the Echo anti-bikie taskforce, Detective Inspector Graham Banks, says the big bikie groups are recruiting street gang members from adult prisons to act as their muscle.

Patton says one of the best weapons against bikie and Middle Eastern drug syndicates has been Firearm Prohibition Orders that give police unprecedented powers to search people and places subject to FPOs.

The recent international sting where police intercepted millions of encrypted crime messages through the An0m app established the scope of organised crime.

Patton says the Australian arm of the operation, code named Ironside, “saved lives – it stopped criminals hitting other criminals”.

But, he says, “it is frightening how big the problem has become. It is bigger than we thought, and we have so much more work to do.”

All of Patton’s reforms rely on police being able to provide a back-to-basics service that includes visible foot and vehicle patrols, quick responses to emergency calls, immediate intervention in family violence, a capacity to provide large numbers at critical incidents and consistent targeting of street and organised crime groups.

The trouble is that over the years police, as the biggest 24- hour government responder, have been assigned jobs that have little to do with law enforcement. Patton has decided what police need to do. His challenge will be deciding what they don’t need to do.

“We can’t keep doing everything. Some policing roles have nothing to do with policing at all,” he says.

The biggest is mental health, with police responding to a call every 12 minutes and detaining someone to take them to hospital under the Mental Health Act every 40 minutes. No matter how well they are trained, police are not mental health experts, and it is costing thousands of patrol hours.

Which is why the Chief Commissioner will be delighted when (and if) the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Mental Health are adopted, including that the emergency response to such cases be led by health experts rather than police, that paramedics take charge and relevant triple- zero calls be directed to Ambulance Victoria.

As a career policeman, Patton thought he understood the pressure that comes with being Chief Commissioner; after all, he had filled the position when his predecessor, Graham Ashton, was on leave.

“I warmed the seat, but I didn’t own it. You don’t know what it is like until it is yours.”

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article