Heroes’ legacy is turned to dust: He lost so many men in the Afghan conflict, but his one consolation was that they hadn’t died in vain. That’s why Major General CHARLIE HERBERT says today’s retreat is a shameful betrayal of Britain’s bravest

There isn’t a single day or night when I don’t think of them: The soldiers under my command in Afghanistan who were maimed and killed. There are still many moments, I’m not ashamed to admit, when I choke up at the memories and the tears fall.

I am not a man easily moved to emotion. But today I feel almost overwhelmed – filled with anger, grief and outrage. For what other response can there be to the West’s betrayal of Afghanistan?

For nearly 20 years, British troops have displayed their quiet, consistent heroism to make that far-off country safer.

It’s impossible to count all the lives our soldiers saved, the communities they protected and the families who were given a chance to work and go to school in relative peace.

Despite the many horrors they witnessed and endured, they helped to create a better, safer world and I refuse to believe that their service was not worthwhile.

But by abandoning Afghanistan in such chaotic haste, the US and European governments have squandered their precious legacy. Their bravery and bloodshed has been turned to dust in just a few short days. How shameful. How unforgivable. I barely have the words to describe how enraged I am.

The regions that British troops fought, bled and died for have been surrendered to Taliban control, almost overnight.

It amounts to the worst military humiliation the West has suffered in living memory. That is not hyperbole. It’s no exaggeration to say the US retreat from Vietnam in 1975 was a strategic masterstroke compared to this.

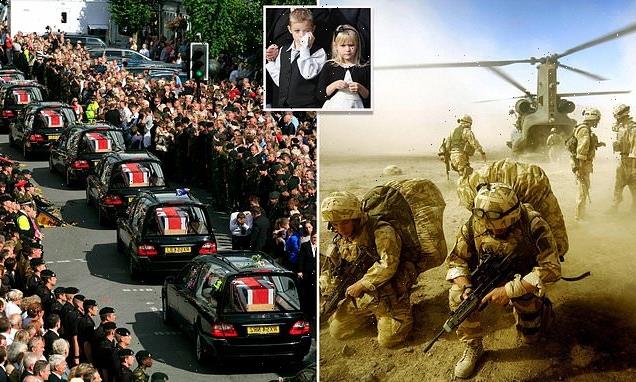

Front line: A helicopter kicks up dust around Commandos in Helmand in 2007

For me, this is not just political but personal. The majority of my soldiering career from 2002 onwards centred on the Afghan campaign, beginning with two years working with the Ministry of Defence in London.

My first tour of duty in the country itself took me to Kandahar province for nine months in 2007. Three years later, I commanded the 1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland in Helmand. And I returned in 2017-18 as the senior Nato adviser to the Afghan ministry of the interior.

On each tour I was embedded with the Afghan security forces – living and fighting alongside them, often under fire in some of the most dangerous regions.

In 2010, one of my companies was stationed at Patrol Base Wishtan in Helmand in what was beyond doubt the most deadly square kilometre in Afghanistan – and probably anywhere in the world.

Our enemies were insurgents, backed by Pakistan and Iran, as well as local tribesmen settling old scores in disputed territories.

They fought a classic insurgency campaign against us and they did it ruthlessly.

The company of 2 Rifles that was there before us suffered the worst day for British troops of the entire campaign, with five dead and ten wounded by improvised explosive devices [IEDs] in a single day in 2009. Many of the survivors suffered appalling mental trauma and at least one later tragically took his own life. The intensity of patrolling in those roads and alleyways, where bombs could lie hidden at every step, is unimaginable.

Every day, our boys were sick with nerves but still did their duty with unwavering bravery. They knew that a single mistake at any moment could leave a man with his legs and hands torn away – if he wasn’t killed on the spot.

Added to that was the constant expectation of sniper fire or of attacks with rocket propelled grenades (RPGs) and mortars.

During that tour in 2010, I had three of my own soldiers killed in action – Lance Corporal Joe Pool, Corporal Jon Moore and Private Sean McDonald.

A dozen more were seriously injured. One of my interpreters lost three limbs. Years later, I feel their loss as keenly as ever and I am in touch frequently with the parents and families of my dead comrades, as well as with many of my former soldiers themselves.

Mourning: The coffins of the fallen are saluted in the streets of Wootton Bassett in 2009

Chloe and Conner Lockett, children of Acting Sergeant Michael Lockett during the funeral of their father at Cathcart Old Parish Church in Glasgow in 2009 after he was killed in Afghanistan

Bin Laden, Bush and 20 years of blood and sacrifice

SEPTEMBER 2001: WAR ON TERROR

After the September 11 attacks, US President George W Bush blamed the Taliban regime for sheltering al-Qaeda chief Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan and declared a ‘war on terror’.

Then-PM Tony Blair promised unequivocal support, saying: ‘We here in Britain stand shoulder to shoulder with our American friends.’

OCTOBER 2001: AIR STRIKES BEGIN

Less than a month after 9/11, Mr Blair confirmed British forces would be involved in US-led military action against al-Qaeda training camps and the Taliban regime. Allied air strikes began.

In November, the first UK troops were deployed, when Royal Marines from 40 Commando helped to secure Bagram airfield.

DECEMBER 2001: TALIBAN ROUTED

The Western-backed Northern Alliance captured Kabul within weeks of the first air strikes. The Taliban was forced out of Kandahar, its last stronghold, in December. An interim power-sharing government was led by Hamid Karzai.

Mr Blair hailed it as ‘a total vindication of the strategy we have worked out from the beginning’.

2003: INSURGENTS FIGHT BACK

As the eyes of the world turned to war in Iraq, the Taliban leaders – who had taken refuge in neighbouring Pakistan – started to regroup in Afghanistan, setting up training camps in the mountains.

JANUARY 2004: FIRST UK DEATH

Militants started to use suicide bombings to target international forces. Jonathan Kitulagoda, 23, was killed in a suicide attack near a military base in Kabul.

2006: HELMAND AND CAMP BASTION

Amid growing insurgency in the south, British forces were redeployed and based at Camp Bastion, near Lashkar Gah in Helmand. The vast majority of the 457 British servicemen and women who died in Afghanistan were killed in Helmand.

During a visit to the base, Mr Blair said that Bastion was ‘where the fate of world security in the early 21st century is going to be decided’.

SEPTEMBER 2006: THE WORST DAY

An RAF Nimrod plane crashed during a reconnaissance mission over Helmand on September 2, killing all 14 crew. The crash was the biggest single loss of life for British forces since the Falklands war in 1982.

2008 and 2012: HARRY’S SERVICE

Prince Harry served two tours, becoming the first royal on active duty since the Falklands. A media blackout surrounded his first active tour in 2008, although it was broken by a foreign website.

Captain Wales returned in 2012 for a four-month tour as a pilot of an Apache attack helicopter. He said that he had fired on the Taliban to support ground troops and rescue injured Afghan and Nato personnel.

2009: BRITAIN’s BLOODIEST YEAR

A total of 109 servicemen and women were killed in this single year.

MAY 2011: BIN LADEN KILLED

US special forces shot dead Osama Bin Laden in a raid on a fortified compound in Pakistan on May 2. Later that year PM David Cameron reduced troop numbers in Helmand and signalled that Britain would end all combat missions before 2015.

OCTOBER 2014: WITHDRAWAL

Britain withdrew combat troops from Helmand and handed over Camp Bastion to the Afghan army.

JULY 2021: FINAL DRAWDOWN

Boris Johnson confirmed most British troops had left Afghanistan last month, following the decision by the US to withdraw its soldiers.

We maintain a support network because, no matter how hard they try, nobody who was not there can ever fully comprehend what we went through.

Two of my men who died were killed on a night patrol near Sangin in Helmand. Corporal Moore was commanding a section south of the company base when he and his lead man, Private McDonald, were killed when an IED detonated.

Jon, who was 22, was a true Scottish warrior, as charismatic as he was tough. Brought up in Hamilton, he was destined for high rank. All his mates knew him for his love of indie rock music. His commitment to making Helmand safe for ordinary locals was unflinching.

‘Mac’, born in Toronto but raised in Edinburgh, was 26, a senior soldier. He had the stomach-churning job of clearing the streets of explosives, keeping fellow troops and civilians safe.

He was, as one of the other officers described it, ‘the tip of the spear’. I was in awe of him and his courage, not least of his talent for mixed martial arts and cage fighting.

Joe Pool from Greenock was killed during an early morning operation in the Nad Ali district, searching compounds for insurgents and weapons caches. He was serving with the Brigade Reconnaissance Force [BRF], one of the most dangerous jobs, when they came under fire. Joe was killed by an RPG.

Aged 26, he had a fiancee and two sons, Lee and Jamie, who were seven and two when their father was killed. They can take comfort from the knowledge that their dad was helping to protect the Afghan people from a barbaric enemy, and that as a volunteer for the BRF he had proved himself as the very best. He was always at the forefront.

So many brave men and women killed. So many coffins sent home for that sad final parade through the streets of Wootton Bassett, in Wiltshire. So many families left facing a lifetime of grief.

I’m so proud of all those who sacrificed their lives for not only fulfilling the soldier’s contract to fight for Queen and country but also for a better world.

I know how grateful thousands of Afghan families are, especially those whose young women have grown up able to go to school and university, and build careers.

How must those grieving British and grateful Afghan families feel today? To see all that progress dismantled in the space of a month or less must be utterly shattering.

For my part, I feel as if I’m living through a nightmare from which I cannot wake up.

Worst of all is the utter betrayal of our loyal Afghan partners on the ground, including those who were trained by Britain and the interpreters who deserve protection but have now been abandoned.

I communicate with many of them daily and to be unable to save them now is the most frustrating, distressing experience I have ever known. One man called me from Kabul yesterday to say he’d seen the government helicopters leaving.

‘What are we meant to do?’ he asked. There was nothing I could say. The scale of the collapse is abject.

There are those who argue that the West was left with little alternative. With support waning in America and the Taliban resurgent, we could not stay in Kabul for ever, goes their thinking. Perhaps not.

But I refuse to believe an orderly withdrawal was impossible. The Russians didn’t retreat in such chaos in 1989 – even as the Soviet Union was crumbling. How could the West have made such a shambles of it? Besides, the price we will pay for retreat is likely to be far greater than the risks from remaining to hold the peace for a few more years.

The likelihood now is Afghanistan will become an incubator for global terrorism, just as it was 20 years ago.

I can’t blame the Afghan army and police for allowing the Taliban to roll into the capital city without resistance. No one can be expected to stay and fight when their leaders are already fleeing. But I do blame the UK, European and American policymakers for not holding to their pledges.

We told our partners that we would stick by them. What nation now will think our word is our bond?

As for the people of Afghanistan, the majority will cope. They are a nation of survivors who have experienced 40 years of war. But a generation of young women will no longer have the opportunities that we fought to ensure for them. Already women in Kandahar are being ordered to leave their jobs and stay indoors.

Worse, though, will be bloody retribution for many who bravely sided with the West. In the Lashkar Gah district, a number of interpreters and local staff – men I worked with, whom I know and respect as brave colleagues – are now in hiding from the Taliban. They know they face torture and execution if they are captured.

I was one of 45 senior retired officers who wrote to Prime Minister Boris Johnson three weeks ago to express our concern for the interpreters.

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has boasted about how Britain has successfully safeguarded these people, and he has sought to discredit newspaper stories of the dangers they face. How hollow those boasts now sound.

And where was the Foreign Secretary, as the window to help those brave souls began to vanish and the weeks became days to get them out to safety? On his summer holiday.

There are no words adequate to describe what a shameful dereliction of duty that is.

MAJOR GENERAL CHARLIE HERBERT undertook three tours of duty in Afghanistan between 2007 and 2018.

Source: Read Full Article