‘My wife’s suicide broke my heart. Only the ice gives me peace’: Iceman Wim Hof has become a global star thanks to his extreme feats of endurance but as he reveals he owes his obsession to that tragedy that almost destroyed him

Wim Hof sounds like a man with a death wish. How else to explain his history of climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in just shorts and sandals, running a half-marathon above the Arctic Circle barefoot, or going swimming in water so cold his corneas froze?

The 62-year-old grandfather, who goes by the nickname The Iceman, says the opposite is true. His wish is to live, ‘to really live’, he tells me.

He performs the splits on our Zoom call to illustrate how much verve you end up with, in your 60s, if you follow his methods. Crikey. His shorts today are very short. Where to look?!

Afterwards, he beams into the camera, all beard and beany hat (‘my wife loves me in my beany hat’). Bear Grylls looks like a staid marketing executive compared with this guy.

Hof is an extreme endurance enthusiast whose antics emerging himself in ice have won him 26 Guinness World Records. He is also into breathing techniques, yoga, extreme balancing and motivational speaking, and has wrapped this all up into the highly marketable Wim Hof Method.

Wim Hof sounds like a man with a death wish. How else to explain his history of climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in just shorts and sandals, running a half-marathon above the Arctic Circle barefoot, or going swimming in water so cold his corneas froze?

With millions of devoted followers, he is something of a god in Hollywood, where his fans include Oprah Winfrey, Gwyneth Paltrow and Matt Damon. Joseph Fiennes is possibly sitting in an ice-bath at this very moment, in training to play him in a forthcoming biopic.

Tomorrow, the Wim Hof Method arrives in the UK with a prime-time BBC show, Freeze The Fear With Wim Hof, where he plunges celebrities including Alfie Boe, Gabby Logan and Tamzin Outhwaite into his world. A world which was once deemed perfectly nuts, he admits.

‘I was this crazy person who did crazy things,’ he beams. ‘But just today a big company asked me to fly to England to give a one-hour talk, and they said they will pay me 50,000 Euros for it. For one hour! Twelve years ago I was making seven Euros an hour. I am not crazy — the world is crazy!’

Wim first felt compelled to step into icy water when he was 17, and walking across a park in his native Amsterdam. There was a layer of ice across it, and driven by ‘what if?’, he just stripped off and stepped in. There was no going back.

‘It took my breath away but afterwards I felt this immediate sense of calm,’ he says. Devotees of wild swimming will possibly recognise that feeling, but Wim has taken things to another level.

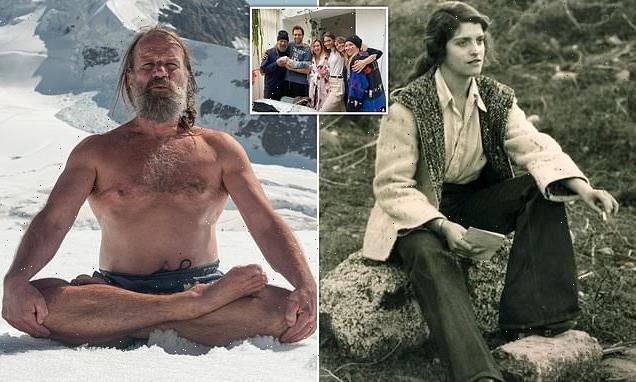

On his website, he says it was the death of his first wife in 1995 that caused him to recognise the link between cold swimming and therapy. The short story is that he found his grief could only be managed by plunging himself into ice. Pictured: His late wife Olaya

He has taken an icy swim pretty much every day since and has encouraged his children to do the same (a super cold shower is apparently the way to start the day in the Hof household).

He is convinced his methods can cure all manner of physical and mental ills by lowering the heart rate, reducing inflammation in the body and making us all . . . well, a little bit superhuman, like him.

To say he is driven is an understatement. But driven by what?

On his website, he says it was the death of his first wife in 1995 that caused him to recognise the link between cold swimming and therapy. The short story is that he found his grief could only be managed by plunging himself into ice.

The longer story — which he relates in full for the first time today — is heartbreaking, a tale of the limits of human endurance.

His wife Olaya, whom he met when he was just 22, was ‘the love of my life’.

Celebration: Wim Hof with his new grandchild, Kai, his son Enahm and family

During the early days of their marriage, she suffered from what he thought was mild depression. By the time their four children had arrived, she had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. In 1995, when their children were aged from seven to 12, she took her own life by leaping from the eighth floor of a building. It almost killed him, too.

‘Afterwards I did not know what to do with my grief. People would say ‘my condolences’. What do I do with that?’ he bellows.

‘My heart was broken. It is a physical thing as much as a mental thing. The only thing that gave me peace was the cold. Cold, hard nature is the cure, I am convinced of it. It allows us to live, and to handle our grief.’

Now — armed with the science and the experience — he believes that his wife, too, could have been saved, had he ‘had the tools then’.

‘I didn’t know all this then, so I couldn’t save her, but I could have. I could have made an intervention,’ he says. ‘Now, I do work with people who have mental illness. I have helped people who are having suicidal thoughts. My wife’s death inspired this, and it is her legacy.’

He met Olaya, whose full name was Marivelle-Maria, in 1982 when he was living a carefree, hippy-style life in a squat in Amsterdam.

Originally from Pamplona in Spain, she had just finished her studies and loved his bohemian kookiness; he thought she was the most amazing woman he’d ever met. ‘I called her my butterfly,’ he says. ‘She was beautiful, she could talk to anyone.’

The pair had a connection that transcended anything he had experienced before. ‘We slept together for a year and we did not have sex,’ he says. Why not? He shrugs, expansively. ‘We did not need it. We had such a strong emotional connection. We were as one.’

Pictured: Wim Hof with Owain-Wyn Evans and Dianne Buswell in Freeze The Fear

She left, though, to go travelling. ‘Then I got a letter from her — she wanted to come back.’

When she did, ‘we slept together, four times in four months’. His eyes cloud. ‘I think I saw a shadow in her then.’

Like her butterfly namesake, Olaya flitted away from him again, leaving him again to do more travelling.

‘I thought it was over, but she was pregnant. When I got the message, I went to Pamplona and her father looked me in the eye — the most penetrating look I’ve ever had. I said: ‘I love your daughter.’ And that was it.’

They got married and started their family, having four children — Enahm, Isa, Laura and Michael — over the next six years.

The family were living in an apartment by this point, which meant compromising on his bohemian lifestyle. He took a series of jobs — from tour guide to postman — to pay the bills.

Yet by the time their family was complete there were serious problems. What he thought were depressive tendencies in his wife were becoming something else.

He wonders if the stress on the body that pregnancy exerts also affected her mind. ‘The hormonal balance can affect the dopamine and serotonin. She wanted a family as much as I did. Our children were beautiful. They were blessings. But two years after the last one, everything changed.

‘It was gradual at first. She would have these down periods, followed by up ones. She would be the perfect mother for weeks, months, then she would just lie in bed and not get up. Her behaviour became more erratic.’

It sounds like a marriage in crisis. He was still living his bohemian dream — he wanted to take his children swimming and embracing the outdoors (‘I was the playful one’) — but this was no longer what Olaya wanted.

‘That side she loved of me, she wanted to change. She wanted me to be more . . . normal and conventional’.

Holly Willoughby with Lee Mack for Freeze The Fear, Wim Hof’s television programme

Is it true that she hated the deep water exercises of which he was so fond? ‘Yes, exactly,’ he says. ‘I was an outlier when we met and she liked that, and she did them to a point, but when you have been with someone for a long time, and you have children, you want something else.

‘She would say: ‘I don’t want to do these strange exercises. I don’t want to go into the cold, doing this breathing. Can’t you be normal?’

He says he was the main carer for the four children long before Olaya died. ‘They lost her before they lost her,’ he nods. He says she would go to stay with her parents in Spain for lengthy periods.

‘But she always loved her children. She loved her children to death, literally.’

For Olaya was, he admits, a danger to her children, and to herself. Having eventually received a diagnosis of schizophrenia, there were appointments with psychiatrists. Pills were administered.

He is scathing of all this; angry even. ‘The pills, the medication, the injections. They not only didn’t help. They made it worse. They said she had seven personalities.’ He is almost crying by this point. He wishes he had taken all seven of those personalities and held them under water, to cure her.

‘If I’d known then what I know now, I could have done something. But I was powerless. I felt completely alone. We didn’t know as much about mental illness then as we do now.’

I ask him about his lowest point and he braces, as if stepping into the ice. ‘Once, she was behind our son, with a knife,’ he admits. ‘My son escaped. He ran away. She was saying he had to die to live.’

The voices were telling her to kill her own children? He nods. ‘She thought by throwing them from the flat down to the ground, she would save their sprits, their beings. She loved them.’

Did she hurt you, too? ‘She didn’t hurt me, no. There were arguments. I would say ‘this cannot go on’ and be greeted with apathy.’

They lurched between apathy and violence, however. ‘You never knew what was coming, or when,’ he says. ‘It would be quiet, normal, for weeks, then it would come out of the blue. She did hurt herself. She cut herself in the throat.’ He makes a violent stabbing motion. ‘She cut her wrists, her arms. I had to hide all the knives.’

Olaya was staying with her parents in Spain on that fateful night in 1995 when she eventually took her own life, aged just 35, having kissed her children goodbye only moments before.

It’s unclear as to whether they were still together at this point. He says they were, ‘although she had said she wanted a divorce, but I think that was one of her personalities telling her to say goodbye, because she always came back’.

Until she didn’t.

And Olaya’s legacy is, it seems, this extraordinary empire which is partly about self-improvement, partly about self-preservation. The fact that it was his eldest son, Enahm, who encouraged Wim to pursue his hobby as a business is interesting. Wim says his children think of his work as a constant ‘tribute to their mother’

He was leading a tour party when he received a message to call his wife’s family in Spain urgently. She had leapt to her death at 2am, on the night after one of the town’s famous bull-running festivals.

Even though he had lived with this possibility for a long time, it was still a ‘deep shock’.

‘I went, that same day, to Pamplona. I could not believe it. Your mind goes ‘the children, the children’, like you are in a fire and there is an adult in danger, you still think ‘the children’.

‘I was in the blackest place you can be. It was dark. Black. It’s as if someone has hit you and everything has stopped.

‘I went to the morgue with her father. And there she was. But the strange thing is, she looked peaceful. I saw peace in her face. All that terror that I’d seen before had gone. In a way, you realise that person is better off in this state, because she is not any more in terror.’ He pauses. ‘She was beautiful, inside and out.’

And Olaya’s legacy is, it seems, this extraordinary empire which is partly about self-improvement, partly about self-preservation. The fact that it was his eldest son, Enahm, who encouraged Wim to pursue his hobby as a business is interesting. Wim says his children think of his work as a constant ‘tribute to their mother’.

‘I’m 62 and I am more fit than a youngster,’ he says. ‘And anyone can do this, I tell you. This is for health, physical and mental’

One daughter has also trained in his methods, as has his second wife, the mother of his youngest child, a four-year-old son. He now has six children in total. There was another relationship between his two marriages, but he has not seen the son from that for 12 years.

‘There is bitterness there,’ he says, wincing a little at another of life’s fails.

In the past few weeks he has welcomed his first grandchild, a baby boy called Kai, ‘which means sea’. So how soon will Kai be having icy swims?

‘Well, my youngest child is now four and when he was one year old, when he could barely walk, he was walking over the ice on the lawn with me, barefoot. And he loved it, and it will strengthen his immune system, strengthen everything. It’s what I am all about.’

Though intrigued cardiologists are carrying out a raft of tests on Hof — and his identical twin brother for comparison — his methods remain contentious. Four people died in 2015 and 2016, with their relatives blaming his methods, while his critics says he overstates the physical benefits.

That is he now moving into the prime-time ‘entertainment’ world just muddies the icy waters further, surely? He disagrees, raising his arms, fists clenched, to show off his muscles. He will spend his 63rd birthday, next week, in a vat of ice, staying there for 63 minutes.

‘I’m 62 and I am more fit than a youngster,’ he says. ‘And anyone can do this, I tell you. This is for health, physical and mental.’

His late wife would agree, he is sure. ‘She is still watching over us. I think she is our guardian angel. This is her legacy. All this is because of her.’

- Freeze The Fear With Wim Hof, tomorrow, BBC One, 9pm.

Source: Read Full Article