The great recycling myth: We spend hours sorting our plastic, cardboard and glass, but less than HALF is actually recycled – and, as a new book reveals, we throw away 20million slices of bread a day and a quarter of clothes are never even sold

Human beings have always produced waste, but never on such a scale as now. Take plastic bottles. More than 480 billion are sold worldwide every year — approximately 20,000 every second. Stretched out end to end, they would circle the globe more than 24 times.

And they’re not even the most numerous item making up this tsunami of trash. That dubious honour goes to the four trillion plastic cigarette filters casually flicked to the ground and stamped out annually.

The numbers are so eye-watering as to be almost impossible to comprehend. In Britain, the average person generates 1.1kg of waste every day; in the U.S., the world’s most wasteful nation, the number is an astonishing 2kg. In 2016, the last year for which reliable data is available, the world as a whole produced a staggering two billion tonnes of solid waste.

The wealthier you are, the more you waste, and so as the developing world grows richer, the problem is accelerating. By 2050 we will be producing a further 1.3 billion tonnes a year, much of that in the Global South.

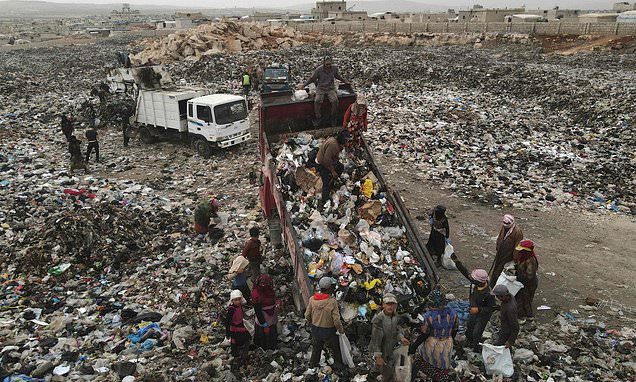

Yet two billion people currently live without access to solid waste collection, and fully a third of the world’s solid waste is dumped or burned in the open air and blown or washed into our rivers and seas, where it joins the toxic out-fall from sewers, factories and power stations.

We all spend hours diligently sorting our plastic, cardboard and glass. But, shockingly, less than HALF is actually recycled

As a new book reveals, even that pales into insignificance when you learn we throw away 20million slices of bread a day

Plastic waste is turning up in the melting glaciers of Everest and in our deepest ocean trenches. A few years ago, the submarine explorer Victor Vescovo attempted to reach the deepest point in the Pacific. There, 10,900m below the surface, in the lightless void of the Mariana Trench, he looked out of the window and saw a plastic bag.

On the surface of the ocean, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the widening circle of water that collects much of the estimated 11 million tonnes of plastic dumped in the oceans every year, is now three times the size of France.

But how can this be given the relentless drive for recycling over the past decades? Around the side of my house are no fewer than seven bins — a purple one for rubbish; black for mixed recycling; blue for paper; dark brown for food waste; light brown for garden waste; and two of our own, for compost.

I’ve spent hours washing out yoghurt pots, crushing plastic bottles, tearing oily patches from pizza boxes so as to salvage the rest. In Britain, we are constantly harried by ad campaigns, signs and labels into seeing recycling as a civic responsibility. This is for the planet, we tell ourselves. I’m doing something good.

It’s a harsh truth, though, that much of what we thought was being recycled actually wasn’t — and isn’t. For decades, Western nations have offshored our trash to poorer countries where labour is cheap and environmental standards weakest, a phenomenon known as ‘toxic colonialism’.

In the UK, less than half of all household waste is recycled, and much of that is exported. The waste clogging up Asia’s rivers is ours, as we in the Global North with our hyper-consumptive lifestyles, dump our waste on the margins, and on the marginalised.

On the plus side, though, globally as many as 20 million people make a living as waste pickers. They go by many names: in Egypt, they are zabaleen, in Mexico, pepenadores, in Brazil, catadores, in South Africa, bagerezi, in India, kabadiwala (‘rag men’). They crawl through mountains of rubbish, finding value in what we throw away. In one man’s trash, another’s treasure.

And recycling is doing good, mostly. Recycling an aluminium can requires roughly 92 per cent less energy and emits 90 per cent less carbon than making one from virgin metal. For every tonne of aluminium saved, you’re also saving eight tonnes worth of bauxite ore from being mined.

Recycling one tonne of steel requires just a quarter of the energy of making it new, cuts the associated air pollution by 86 per cent, and saves around 3.6 barrels of oil. Recycled glass requires 30 per cent less energy to produce, paper 40 per cent less, copper 85 per cent.

By recycling, we’re also reducing the environmental damage caused by extraction: the logging, mining, processing, and transportation required to replace those items with new.

Recycling creates less water and air pollution. It reduces the amount of waste that then ends up in landfills, dumped or burned. The recycling industry employs millions of people around the world; the market for scrap metal alone is worth more than $280 billion. Recycling schemes create 70 jobs for every one that would be created by landfill or incinerators.

Also revealed in the book is that a quarter of clothes are never even sold

Recycling creates less water and air pollution. It reduces the amount of waste that then ends up in landfills, dumped or burned

And the scale is enormous: 630 million tonnes of steel scrap is recycled globally every year. It’s estimated that 99 per cent of the metal in scrapped cars ends up reused. Of all the copper ever mined, 80 per cent is still in circulation.

In the UK, three-quarters of glass waste is recycled into new bottles, fibreglass or other materials. There is little doubt that recycling most materials is a better solution than burying or incinerating them. The problem is plastics.

Plastics don’t just end up as waste, they begin as waste. The chemical building blocks of many plastics — ethylene, benzene, phenol, propylene, acrylonitrile — are inherently waste products, created in fossil fuel production. They were habitually burnt or released into the atmosphere until the 1920s and 1930s, when enterprising oil and coal industry scientists discovered ways to solidify them into polymers.

World War II triggered a plastics revolution. Parachutes, cockpits, radar systems, combat boots, ponchos, bazooka barrels — all were moulded with the new materials being churned out of the labs at the likes of Dow Chemical and DuPont. Between 1939 and 1945, global plastic production increased nearly fourfold. Soon, many of those same materials — Nylon, Perspex, polyethylene film — were flooding into households.

For all their flaws, plastics are a miraculous class of materials: cheap, elastic, lightweight, durable, capable of taking on almost any shape or colour. Suddenly, here were materials that could be stretched into sandwich wrap or hardened into a car bumper, moulded into an intravenous tube or spun into a T-shirt.

Ivory, wood, cotton, whalebone, leather — plastics could imitate them all. Pretty much anything could be plasticised. Pretty soon everything was, burying the burgeoning middle classes under an avalanche of stuff.

What fuelled this bonanza was the realisation by the new plastics industry that profits lay not in creating high-quality products with innate permanence but in the opposite — single use.

Manufacturers were soon pumping out disposable versions of almost anything: pots and pans, plates, cutlery, towels, dog bowls. Drinks once sold as refills were now packaged in bottles or plastic cups designed to be tossed away after one use.

Rubbish dumps and incinerators were soon overflowing with plastic bottles, plastic jugs, plastic tubes, blisters and skin packs, plastic bags and films and sheet packaging.

The very characteristics that make plastics extraordinary are those that make them so problematic as waste. The covalent bonds that bind their molecules together are durable to the point of stubbornness. Almost nothing alive digests them, so they do not decompose.

When plastics are broken down, by ultraviolet radiation, by the elements or by force, they do not disintegrate so much as divide, their chain-like structures splitting into smaller and smaller pieces of themselves. Macroplastics become microplastics become nanoplastics.

By then they are small enough to enter our bloodstreams, our brains, the placentas of unborn children.

The impacts of these materials on our bodies are only just beginning to be understood; none are likely to be good. This is the bad news.

The good news is that some plastics are now proving recyclable, notably polyethylene terephthalate, otherwise known as PET. This extraordinary material can be transparent or coloured, and its natural flexibility makes it specially suitable for fizzy drinks, holding on the lid and not exploding as the gases build up.

Significantly, it is also thermoplastic — that is, it can be easily melted down and recycled (as opposed to thermoset plastics, such as polyurethane, which cannot). And it is that ability that has now reset the recycling industry.

Until recently, the plastics industry considered recycling an unrealistic solution to its waste problem. It would make big promises about moving to more recycled content and even open new facilities, only to abandon them when public attention moved on.

The dynamic changed in 2017 when the BBC’s Blue Planet documentary graphically depicted the horror story of sea turtles choking in plastic rings from six-packs and whales washing ashore with stomachs full of plastic. This triggered a moral awakening in Britain, with packaging brands falling over themselves to adopt recycled plastics.

PET’s day had come. It could be processed into a pellet and sold back to the drinks manufacturers to be made into a new bottle. The surge in demand made it a highly profitable operation, as I witnessed at a new plastics recycling plant overlooking the North Sea where up to 57,000 tonnes of PET can be recycled every year — the equivalent of 1.3 billion bottles.

So far, so good. But the problem with plastic recycling is that we don’t really know how much it actually happens. In 2020/21, the official national recycling rate for England was 43.8 per cent of household waste. However, that figure measures the amount of waste that enters recycling facilities, not what is actually being recycled, a definition hidden inside obscure government documents.

Which is to say the nation’s top-level recycling figure is a measure not of outcome, but intent: at best a flawed method of data collection, and at worst intentionally misleading.

The problem with plastic recycling is that we don’t really know how much it actually happens

And the fact is that nearly half the plastic waste that arrives for recycling is not recycled into new PET because of contamination by other substances collected from household bins. It can only be incinerated. In other waste streams, such as the recycling of plastic films, yield can be even lower.

This fundamental data gap is also true in Germany, a country hailed for being the world’s best recycler. It employs a similar calculation method, and overstates its recycling rates by 10 per cent. In the U.S., the true recycling rate for plastic is just 5 per cent, nearly 40 per cent lower than official estimates.

The reality is that collecting, sorting and separating most plastics is expensive and impractical. Plastic bags and films can be recycled, but companies have historically avoided them because they snag and clog up machinery. Polystyrene can be recycled, but degrades quickly.

That’s before you get to multi-layered plastic, the highly engineered films and tube packaging used to make everything from toothpaste tubes to crisp packets.

If we really want to fix plastics recycling, we need a much more radical approach. For example, get rid of multi-layered films and multi-material packaging. Why are we still selling sandwiches in cardboard and plastic? Do it in cardboard or do it in plastic, but not both.

But to really fix recycling for all plastics will require a far greater commitment, and investment everywhere. It will also require everyone in the recycling industry to tell the truth about what is being recycled, and what isn’t.

Worldwide, more than 931 million tonnes of food goes to waste every year, according to the UN. Up to a third of all food produced is discarded without being eaten. That’s $1 trillion’s worth every year, enough to feed two billion people, or every single undernourished person in the world four times over.

The U.S. discards 63 million tonnes of food waste — putting it among the more wasteful nations per capita. But this profligacy is not just a Western phenomenon. China throws out a staggering 350 million tonnes of food every year, India 68.8 million.

Almost anywhere you find food, you’ll find it wasted — in the fields, thrown away during sorting, discarded during manufacture and tossed out at retail. The majority, however, comes at home — the food we leave rotting in our refrigerators and scrape into the bin from unfinished plates.

And this is not just a human tragedy, but an environmental one, too. Rotting food throws off huge amounts of methane, generating 3.3 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases, or 10 per cent of all global greenhouse gas emissions. If it were a country, food waste would be the third highest emitter on earth, behind only China and the U.S.

Experts like to differentiate between food loss, the food wasted on farms or in manufacturing, and food waste, which is lost at or after the point of sale, by restaurants, retailers or consumers.

This is for good reason: while food is wasted everywhere, it is not always for the same reasons. In the Global South, a disproportionate amount of food is lost in the production process — due to the warmer climate, inadequate storage or refrigeration and pests. In the Global North, the majority is thrown away within households.

Differences can also be cultural. For example, the Koran expressly condemns food waste; in many parts of China, on the other hand, it is considered rude to finish your plate, lest you insult your host’s generosity. So much food is wasted by this practice that the Chinese government instituted fines for restaurant customers who leave excessive amounts on their plates.

Here in the UK we throw away 6.6 million tonnes of edible food per year, the calorific equivalent of ten billion meals. The average household spends £700 per year on food that they don’t eat. Forty per cent of salad leaves go uneaten. So do 400,000 tonnes of meat (chicken, the cheapest meat, is the most wasted) and 490 million pints of milk.

But the most wasted product is bread, more than 900,000 tonnes of it every year, or 20 million slices every day. Tesco estimates that 44 per cent of all white sliced bread is never eaten.

Mostly this happens because we buy loaves that are too big and go stale or mouldy before we get a chance to finish them. Then there’s the bread lost in retail and manufacturing: in sandwich factories it’s not uncommon for the end slices of every loaf to be thrown away.

The resources wasted on producing uneaten food are even more valuable than the food itself. Up to 1.4 billion hectares of land used for farming — as much as 28 per cent of all farmland worldwide — is being wasted, when it could be put to other uses, such as housing or planting forests. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the farmland we use to grow uneaten food could cover the entire Indian subcontinent.

It’s the same profligacy with water. Seventy per cent of the planet’s fresh water usage is for agriculture. One in five litres of fresh water is being used to grow food that is never eaten by people.

What matters is what else could have been done with all that land, water and labour. Instead of growing a tomato that ends up being thrown away, that farmer could have put the land and energy to growing wheat, which is more energy-efficient, calorifically dense and less perishable.

According to one expert, the energy that goes into growing the 61,300 tonnes of perfectly good tomatoes that people throw into their household rubbish bins in the UK could grow enough wheat to relieve the hunger of 105 million people.

There are many reasons why shops throw away food. Fresh produce might be damaged; tins get bashed and broken and shoppers won’t buy them. Supermarkets also routinely overstock, their aisles overflowing with nearly any kind of food you can imagine, no matter how exotic or out of season, for fear that empty shelves will encourage shoppers to take their custom elsewhere.

Retailers also spend billions encouraging us to buy in bulk — making food cheaper to buy through heavy discounting and deals like ‘Buy One, Get One Free’, but also ensuring more goes to waste.

Seventy per cent of the planet’s fresh water usage is for agriculture. One in five litres of fresh water is being used to grow food that is never eaten by people

What’s more, much of the food we buy is portioned according to the needs of the average household — the fabled nuclear family of four — rather than an individual, a problem in a society where more and more people live alone, and where even in families people increasingly eat different meals at different times.

Food waste also creates other kinds of waste. It can be hard to find fresh produce that isn’t wrapped in cling film and/or served inside a plastic tray.

Food companies argue that plastic wrapping extends the life of fresh produce, and therefore reduces waste. The reality is more complex. A recent study by the British sustainability charity WRAP found that in most cases, plastic-wrapped fruit and veg made no difference to shelf life, and actually increased waste overall, by forcing consumers to buy more than they need.

Plastic, it turns out, appears to be excellent for reducing food waste within supermarket and food companies’ supply chains — limiting their environmental footprints, and bolstering their profit margins — but in aggregate, simply acts to move the moment that food is wasted onto customers.

What do retailers do with the waste they themselves end up with? Ninety per cent is either pulped and sold for animal feed, or sent for aerobic digestion to generate energy — often for the supermarkets themselves.

The remaining 10 per cent is generously donated to food banks, the supermarkets patting themselves on the back in the process — though a cynic might suggest that, beneficial as this obviously is, it saves them having to pay for their excess to be taken away. Every kilo of bread or fresh produce donated to a homeless shelter is a kilo they don’t have to pay to incinerate or dispose of in landfill.

Fashion is the business of waste; its very existence is obsolescence. The fundamental job of any clothing company is not to dress you, it is to make you want more clothes.

British adults wear only 44 per cent of the clothing they own. Our wardrobes contain 3.6 billion garments (worth £2.7 billion) that are not being worn.

And fashion’s profligacy is only getting faster. Where major clothing labels once had four seasons per year, many fast-fashion brands can now run new ‘drops’ of capsule collections every day, year-round, enabled by under-paid labour in countries like Bangladesh and cheap Chinese cotton.

H&M can add about 25,000 new products to its website in a single year, Zara 35,000. In the same time period the Chinese fast-fashion giant SHEIN — which in just a few years has gone from virtually non-existent to comprising 28 per cent of the U.S. fast-fashion market — added 1.3 million different new products.

The result of our clothing consumption is a truly prodigious amount of waste. It starts from the factory floor: as much as 12 per cent of fibres are discarded before they even make production. Then there is dead stock, the clothing that brands order but can’t sell.

In some cases, this can be 50 per cent of an item. Throwing away just 10–15 per cent of a design order is seen as good practice.

Overall, it’s thought that 25 per cent of all clothing made is never sold. The quantities involved can be astonishing. In 2018, for example, H&M admitted to hoarding unsold stock worth $4.3 billion, most of which was due to be exported or incinerated.

Most of this stock is simply destroyed. Often, so too are the 25–50 per cent of clothes that are returned, a rate that has only increased with online shopping. Indeed, when the clothes are cheap, landfilling or incinerating them is often less costly than paying someone to process the return.

In total, 85 per cent of all textiles in the U.S. are landfilled or incinerated. H&M produces so much waste that a power station outside Stockholm, where the company is based, switched from burning coal in part to burning clothing.

In the process of our conversion to cheaper clothing, we have largely lost the skills we once had — sewing, darning, cobbling — that would have extended the lives of our clothes. Take a ripped pair of jeans to the tailor to have a seam fixed, and you’ll quickly find that it is cheaper to buy a new pair.

What we wear has become, increasingly, disposable. The amount of clothing bought in the UK per person has doubled since 2000, but the number of times each item is worn has fallen by 36 per cent. At the same time, there has been a tangible drop in quality. Some T-shirts from fast-fashion brands won’t last three washes.

Recently more and more clothing brands have started to incorporate recycled polyester and other plastic-based textiles into their products, advertising it as more ‘sustainable’ than alternatives. In actuality, clothing made from blends of recycled plastics and organic fabrics — cotton and polyester, say — are less recyclable than those made from a single fibre.

A T-shirt cannot be recycled back into another T-shirt. The result is that, globally, only 1 per cent of clothing is recycled.

Source: Read Full Article