Marine veteran John Waters reveals one of his toughest battles came when an opera singer asked him: ‘Do you think a soldier ever comes home from war?’

- John Waters served in Afghanistan and Iraq after attending the Naval Academy

- The Marine veteran is an attorney, but he’s still trying to adapt to civilian life

- He wrote his novel River City One after an encounter with an opera singer

Marine veteran John Waters was at a fundraiser for a local opera singer when he heard a song that reduced him to instinct.

The 37-year-old had been out of the military for four years, plying his trade as an attorney in his native Nebraska and trying to adapt even though he felt ‘off.’

The father-of-three had spent six years in the Marines in Afghanistan and Iraq. He was a ground intelligence officer in Afghanistan – where he located militants with pinpoint accuracy before they were captured or killed.

Later, he became a sniper platoon commander at an infantry battalion, and he ended his service fortifying the U.S. embassy in Baghdad when ISIS was on the rise.

He was adjusting to a new normal of suburban living, corporate functions and lunch meetings when he found himself at the party in the lavish home of a senior partner at his law firm.

After performing a rendition of ‘Danny Boy’ – a song often interpreted as a parent’s message to their son before he leaves for war – the singer asked him: ‘Do you think a soldier ever comes home from war?’

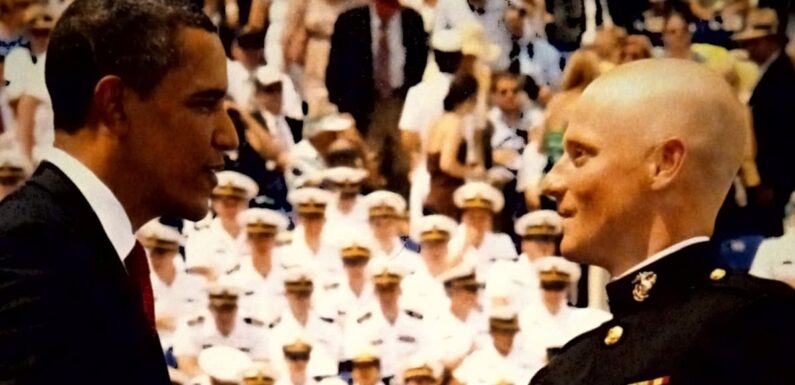

President Barack Obama congratulates Marine John Waters during his graduation from the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. His novel River City One harnesses the struggle of veterans transitioning to civilian life

The question in a room full of people sipping champagne and eating hors d’oeuvres stirred up emotions and thoughts of men tormented by the weight of war.

He felt a spark to write and confront the same question thousands who have served have long sought their own answer to.

He channeled all his experiences from the War on Terror and how he had wrestled with civilian life’s realities in the aftermath.

The men he fought alongside who had suffered deep physical and psychological scars were also at the front of his mind.

‘I imagined everything the Marines in my platoon had been through,’ he told DailyMail.com.

‘More than what was reported, more than what they told me and the things they were afraid to tell me that they were ashamed of.’

What resulted was Waters’ novel River City One, about a Marine veteran, also named John, who is battling the invisible injuries prevalent among service members past and present.

The fictional John Walker is an attorney in a midwestern town struggling through the ‘transition’ veterans go through when they come home from war.

They are faced with loneliness and isolation that only they can adequately describe. They question their identity while life goes on around them.

John Walker wrestles with guilt. His anger towards those who don’t fully understand his internal fight is palpable.

He is trying to survive in a world he still doesn’t fully understand.

At work, he digs deep to find a sense of purpose and belonging. He is surrounded by lawyers in suits who have spent their lives in the safety of an office.

Their battlefield is the courtroom. Just a few years earlier, his was the baron and mountainous hellscape of Helmand Province.

In his first deployment in Afghanistan, Waters prepared briefs and targeting packages for a general in charge of infantry units in Helmand Province. He was shown evidence that the information he obtained resulted in deadly consequences

They are emotions veterans, like Waters, know all too well.

His book is not a memoir, but mirrors what he and many others have experienced in the most dangerous places on earth and what they have faced when they leave.

The story tackles the common questions veterans are asked by people they have never met, such as ‘Did you kill anyone?’ and ‘Could you have done more?’.

When Waters was 18, he could have graduated high school and potentially deployed to Iraq just after the Second Battle of Fallujah – the bloodiest campaign of the conflict for American troops.

Instead, he went to the Naval Academy, majored in English and spent most of his four years playing tennis while also training for a future deployment.

President Barack Obama shook his hand when he graduated.

River City One is about a Marine veteran, also named John, who is battling the invisible injuries that have become too common among service members past and present

He was spurred to join the Marines in 2009 when passers-by approached him while he was in uniform in Washington D.C. and ‘thanked him for his service.

There was a sense of guilt among some who thought they had ‘done nothing’ while the War on Terror was still at its most ferocious.

In 2011 and 2012, he was in Afghanistan preparing briefs and targeting packages for a general in charge of infantry units in Helmand Province.

He was ‘consumed’ by his role in pinpointing the location of Taliban fighters so they could be taken into custody or removed from the battlefield.

‘It was like pinning a wanted sign to their door,’ he says. He was shown evidence that the information he obtained resulted in deadly consequences.

The enemy targets were often hit with HIMARS strikes or tracked down in raids by fellow Marines who spent months going on foot patrols.

They were the infantry units most exposed to IED explosions, close-quarter gunfights, snipers and ambushes.

It was his admiration for these courageous men that, in part, inspired him to become a Marine Scout Sniper platoon leader.

The unit he took over was engulfed in scandal after an arduous deployment.

Marine Corps Captain John Waters launches an RQ-11 Raven unmanned aircraft system in Fort Pickett, Virginia, in 2013

An infamous video surfaced of the Third Battalion, 2nd Marines urinating on Taliban corpses in Musa Qala.

As a result, the Marines had begun cleaning up the Scout Snipers.

When he began, he was ordered to rebuild the unit and help move on the Marines who needed it.

Most in the platoon had seen combat and were drastically changed from when they left home.

Some were still in high school when they signed up for the military, and most were barely old enough to buy a beer.

Waters is now a lawyer in his native Nebraska and has three children

Now, they faced an uphill battle of regaining normalcy and starting their lives again.

Waters started asking questions central to John Walker’s story when he took over the platoon.

‘I wondered, how will these young men who are not who they were when they signed up, how will they ever make it back home?

‘How will they get jobs? How will they be fathers and husbands? How will they be able to pursue happiness like the rest of us?

‘That thought stayed with me, steeped in my imagination for many years.’

‘I saw people who had done courageous things in combat, who had been through multiple tours in places like Marjah and Sangin (in Afghanistan).

‘In many ways, they were the best of who we were as a country through the war. People who had the spirit of 9/11.

‘They fought in the hardest way and the most challenging conditions, and they were changed by war.

‘You could see it on their faces and posture and in their attitudes.’

For Waters, the effects of combat were indebile.

One night in Afghanistan, his base was hit by 120mm rockets, including one that landed close to his tent while he was asleep.

He sat up in his bed bolt upright, his teeth chattering and his body stiff. It was a purely physical reaction.

In the United States, a year later, he had the same reaction when instructors detonated simulated artillery rounds while he was sleeping in a field during mountain warfare training.

Walker also struggles to avoid responses.

A photo of artillery and equipment taken by John Waters during one of his deployments

In 2019, Waters was also trying to adjust to civilian life. He started working as a lawyer in his hometown of Omaha and took all the steps he thought necessary, but his surroundings still seemed ‘off.’

‘I didn’t fit in. I had this feeling. You never really leave behind who you were in the military or who you had to become in war. You never leave that behind.’

In River City One, Walker is also a lawyer who has been out of the military for 10 years. He works in a nameless town and lives in the suburbs with his wife and child.

He works in his office with photos of dead veterans hanging on the walls – instead of the framed diplomas his colleagues so proudly show off.

He attends charity lunches he doesn’t want to and focuses on one case at a time while his partners deal with multiple.

The novel opens with Walker dramatically describing holding a gun above ‘the seam of his pants pocket’ with the hammer cocked, ready to fire – like he is preparing for a firefight.

But he is in a gun range with a fellow veteran, reliving the moments during deployments when sand would be ‘whipped into the air’ and get trapped in the grooves of the gun.

At cocktail parties in houses in the most affluent part of town, he makes small talk as guests ask him ‘what he saw’ and if he killed anyone.

Like Waters, Walker struggles to come to terms with the pace of civilian life while remembering his deployments.

He stays in touch with veterans who have taken different paths in their lives, including a beer-drinking friend who brags about being rid of his wife.

In the book, John also attends a fundraiser by a senior lawyer at his firm and hears an Irish opera singer perform ‘Danny Boy.’

The part of the story most closely reflects Waters’ path.

‘The song reduced me to just instinct. I just felt overcome. I didn’t want to, but I couldn’t help it,’ Waters said after hearing the performance.

‘After she sang, she stopped me as I was leaving. I said, ‘Why did you sing that?’ And she said it’s a song about a mother watching her son march off to war.

He said he had been to war. And she responded with the same question that sparked him to articulate his response.

‘Do you think you ever come home from war?’

When he left the military, Waters’ civilian colleagues would ask how the ‘transition’ was ‘coming along.’

Those still in uniform would ask if he regretted leaving the Marines.

River City One is Waters’ attempt to resolve these questions through the story of Walker and his family.

‘There’s pride that you saw the best in yourself, that you said yes, that you witnessed the best in your friends.

‘But there’s some regret or shame in people’s minds that they didn’t do more.’

Waters hopes readers will appreciate that combat leaves an indelible ‘thumbprint’ on service members.

This ‘thumbprint’ – whether a janitor, accountant or lawyer – means they appear like one person to the rest of the world, while in their head, they’re someone else.

River City One by John Waters is available online and in bookstores.

Source: Read Full Article