Book characters are four times more likely to be male than female, a gender bias study has revealed

- The team used AI to study 3,000 English-language books in Project Gutenberg

- This allowed them to have a constrained dataset for more controlled analysis

- They found that there was a 4:1 ratio of male versus female main characters

- There were also more negative terms used in connection to the female characters such as ‘weak’ and ‘stupid’ compared to ‘strong’ and ‘power’ for men

Characters in books are about four times more likely to be male than female, a new study of gender bias in literature has revealed.

Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering used artificial intelligence to examine more than 3,000 English-language books ranging from science fiction and adventure, to mystery and romance – across short stories, poetry and novels.

The team found male characters appeared four times as often as females across the books, although that reduced when the author of the work was female.

There were also more negative terms used in connection with the female characters such as ‘weak’ and ‘stupid’ compared to ‘strong’ and ‘power’ used for men.

‘Gender bias is real, and when we see females four times less in literature, it has a subliminal impact on people consuming the culture,’ said author Mayank Kejriwal.

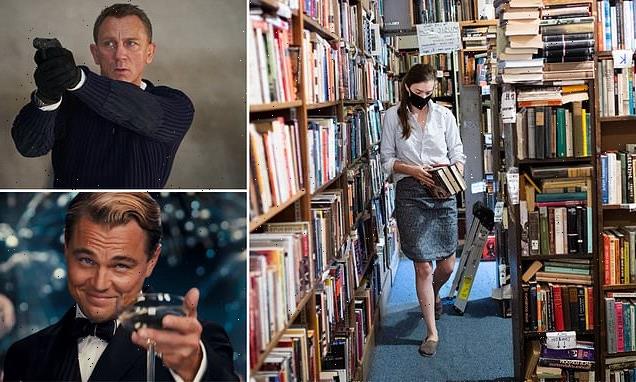

Characters in books are about four times more likely to be male than female, a new study of gender bias in literature has revealed, such as F Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby

Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering used artificial intelligence to examine more than 3,000 English-language books ranging from science fiction and adventure, to mystery and romance – across short stories, poetry and novels

The study, run by the Information Sciences Institute at USC was inspired by other work looking at implicit gender biases, which only give a qualitive result.

The team, including Kejriwal, wanted to quantify the representation of males and females within literature and the wider media using AI techniques.

To produce these findings, Kejriwal and co-author, Akarsh Nagaraj, accessed data through the Gutenberg Project corpus – to create a set text to work from.

Nagaraj said the methods they used, as well as the findings, revealed a greater understand of biases in society, as well as its implications.

‘Books are a window to the past, and the writing of these authors gives us a glimpse into how people perceive the world, and how it has changed,’ he added.

The study produced a number of methods for working out how many females appeared in literature, including something known as Named Entity Recognition (NER), a prominent method used to extract gender-specific characters.

There were also more negative terms used in connection with the female characters such as ‘weak’ and ‘stupid’ compared to ‘strong’ and ‘power’ used for men, such as James Bond

The team found male characters appeared four times as often as females across the books, although that reduced when the author of the work was female

‘One of the ways we define this is through looking at how many female pronouns are in a book compared to male pronouns,’ said Kejriwal, adding ‘the other technique is to quantify how many female characters are the main characters in it.’

This allowed the research team to determine whether the male characters were central to the story, in the 3,000 or so stories published from 1880 to 2000.

HOW ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCES LEARN USING NEURAL NETWORKS

AI systems rely on artificial neural networks (ANNs), which try to simulate the way the brain works in order to learn.

ANNs can be trained to recognise patterns in information – including speech, text data, or visual images – and are the basis for a large number of the developments in AI over recent years.

Conventional AI uses input to ‘teach’ an algorithm about a particular subject by feeding it massive amounts of information.

Practical applications include Google’s language translation services, Facebook’s facial recognition software and Snapchat’s image altering live filters.

The process of inputting this data can be extremely time consuming, and is limited to one type of knowledge.

A new breed of ANNs called Adversarial Neural Networks pits the wits of two AI bots against each other, which allows them to learn from each other.

This approach is designed to speed up the process of learning, as well as refining the output created by AI systems.

The study’s findings also showed that the discrepancy between male and female characters decreases under female authorship.

‘It clearly showed us that women in those times would represent themselves much more than a male writer would,’ said Nagaraj.

There were some limitations to the techniques used by the team, for example if the author was not clearly male or female, they were ignored.

‘When we published the dataset paper, reviewers had this criticism that we were ignoring non-dichotomous genders,’ said Kejriwal.

‘But we agreed with them, in a way. We think it’s completely suppressed, and we won’t be able to find many [transgender individuals or non-binary individuals].’

Kejriwal acknowledged that AI tools for identifying plural words, such as ‘they,’ which may be referring to a non-binary individual, do not yet exist.

They hope the methods they’ve developed can be a framework for future studies, that address these social issues more effectively.

The study also provides a blueprint for future work on quantifying the qualitative findings they discovered through the study’s methodologies.

Without the inherent bias in human-designed surveys, the AI was able to determine adjectives linked to gender-specific characters.

‘Even with misattributions, the words associated with women were adjectives like ‘weak,’ ‘amiable,’ ‘pretty,’ and sometimes ‘stupid,” said Nagaraj. ‘For male characters, the words describing them included ‘leadership,’ ‘power,’ ‘strength’ and ‘politics.”

While the team didn’t ultimately quantify this part of their study, this difference in descriptions between gender-specific characters should be addressed in future, the team said, adding there is merit in ‘more comprehensive qualitative investigation on word associations with gender.’

‘Our study shows us that the real world is complex but there are benefits to all different groups in our society participating in the cultural discourse,’ said Kejriwal. ‘When we do that, there tends to be a more realistic view of society.’

Kejriwal is hopeful that the study will serve to highlight the importance of interdisciplinary research—that is, using AI technology to highlight pressing social issues and inequalities that can be addressed.

The findings have been published in the journal Data in Brief.

Titles with a male protagonist tend to focus on professions and tools, while those led by a female centre on affection and communication

Books designed for children may be perpetuating gender stereotypes, a new study warns.

More than 240 books written for children five years old and younger were analysed by a team from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

They found that books with a male main character were more often about professions, whereas those with a female protagonist were about affection.

‘Some of the stereotypes that have been studied in a social psychology literature are present in these books, like girls being good at reading and boys being good at math,’ said Molly Lewis, lead author on the study.

The authors believe that gendered books read to children in early education ‘could play an integral role in solidifying gendered perceptions in young children.’

Source: Read Full Article