Look up tomorrow! Draconid Meteor Shower will peak on Friday, with up to 10 shooting stars flying through skies over the UK every hour

- The meteor shower will be most visible in the Northern Hemisphere after sun fall

- Those in Northern America, Europe and Asia are the best placed to see the event

- The best view will be under clear, cloudless skies in areas with no light pollution

The Draconid Meteor Shower is set to peak on Friday evening, sending up to 10 shooting stars flying through skies over the UK every hour.

The annual display will be most visible in the Northern Hemisphere after nightfall tomorrow (18:56 BST), in clear skies and away from sources of light pollution.

Meteor showers are caused when the Earth travels through a cloud of cometary debris, putting on a light show for viewers on the ground.

The Draconid Meteor Shower comes from the debris of comet 21 P/ Giacobini-Zinner – a small comet with a diameter of 1.24 miles (2 kilometers).

Meteor showers are caused when the Earth travels through a cloud of cometary debris. In this case, the Draconid Meteor Shower comes from the debris of comet 21 P/ Giacobini-Zinner. Pictured, the night sky over Russky Island during the Draconids

The Draconid Meteor Shower

The Draconid meteors are caused when Earth collides from debris shed by comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner.

The comet has a six and a half year long orbit that periodically carries it near Jupiter.

The rocks, stones and dust particles, which can be as small as a grain of sand, enter the atmosphere, and friction with air molecules cause them to give off bright light.

The best way to see the show is by heading as far away from light pollution as possible.

They are best seen in the evening instead of before dawn as this is when the constellation Draco the Dragon – where the meteors appear to come from – is highest in the sky.

Giacobini-Zinner lays down fresh pieces of debris every 6.6 years as it passes on its orbit through the inner solar system, and the meteors come when Earth passes through this regularly topped up debris field.

To get the best possible view of Friday’s event, find a place with clear skies and far from sources of light pollution like big cities.

There is no advantage to using binoculars or a telescope – observers just need to look up unaided and take in the widest possible view of the sky.

Generally, those in Northern America, Europe and Asia are the best situated to see the Draconids.

The best places in the UK include the renowned stargazing locations, also known as the three ‘Dark Sky Reserves – Snowdonia, Brecon Beacons and Exmoor national parks.

‘The Dracanoid shower will be visible to anyone with clearer skies,’ Annie Shuttleworth at the Met Office told MailOnline.

‘Those in southern parts of England and Wales away from any light pollution are most likely to see the shower.’

According to Shuttleworth, it will be be cloudy and wet across Scotland and northern Ireland with mostly cloudy skies across north Wales and northern England, meaning vision may be impaired in these places.

‘Anywhere south of a horizontal line through Aberystwyth to Norwich could see an hour or two of clear spells – but many in that area will have mostly cloudy skies,’ she said.

Meteor showers are best seen with a good, clear view of the stars on a night with no clouds.

Try to find somewhere with dark skies, an unobstructed horizon and very little light pollution

Make sure there are no direct sources of light in your eyes, so that you can fully adapt to the local conditions and ensure that fainter meteors become visible.

There’s no advantage to using binoculars or a telescope; just look up with your own eyes to take in the widest possible view of the sky.

Source: Royal Observatory Greenwich

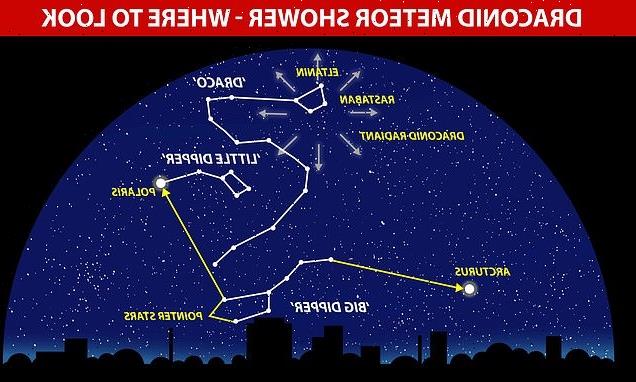

The Draconid Meteor Shower takes its name from the constellation of Draco, which is its radiant point – the point in the sky the meteors appear to come from.

Draco is a long and winding constellation, easily visible to people in the Northern Hemisphere, in the northern sky. It can be found lying above the Big Dipper and Polaris, the North Star.

The Draconids are best seen in the Northern Hemisphere, though it is still possible to see them in the Southern Hemisphere, especially if close to the equator.

That’s because the radiant point for the shower almost coincides with the head of the constellation Draco in the northern sky.

The rate of meteors during the Draconid shower’s peak depends upon which part of the comet’s trail the Earth orbit intersects on any given year, according to Royal Observatory Greenwich.

The observatory describes the Draconids as ‘variable’, meaning you can never be sure what kind of light display you’re going to get.

‘In recent years, the Draconids have not produced any particular outbursts in activity,’ Royal Observatory Greenwich says on its website.

‘However, in 1933 and 1946 the Draconids produced some of the most active displays in the 20th century.’

The Draconid Meteor Shower comes from the debris of comet 21 P/ Giacobini-Zinner – a small comet with a diameter of 1.24 miles (2 kilometers). The comet is pictured here in a shot by the Kitt Peak 0.9-m telescope on October 31, 1998

The shower takes its name from the constellation of Draco, from where in the night sky they seem to originate, which can be spotted lying above the Big Dipper and Polaris, the North Star

REMAINING METEOR SHOWERS IN 2021

- Eta Aquariids – May 5 peak

- Delta Aquariids – July 30 peak

- Alpha Capricornids – July 30 peak

- Perseids – August 12-13 peak

- Draconids – October 8-9 peak

- Orionids – October 21 peak

- Taurids – November 12 peak

- Leonids – November 17-18 peak

- Geminids – December 14 peak

- Ursids – December 22-23 peak

It’s worth noting that 2011 and 2018 saw more Draconid activity than expected, so 2021 could be the year where they put on a spectacular show.

National Space Centre says the Draconids typically produce somewhere between five and 10 meteors an hour, but in past displays there have been thousands per hour.

As the meteors made of ice and dust enter our atmosphere, they begin to burn up – putting on a light show for viewers but meaning that most never reach the ground.

The beautiful streaks seen in the night sky can actually be caused by cosmic particles as small as a grain of sand.

If the particle is larger than a grape, it will produce a fireball and will be accompanied by a persistent afterglow.

Fortunately, there was a new moon on Wednesday, October 6, so the moon’s illumination is going to be at only 6 per cent on Friday, meaning moonlight shouldn’t dim our view of the Draconids.

‘The moon is new on the night of greatest activity, so its light won’t interfere with the view,’ Dr Robert Massey, deputy executive director at Royal Astronomical Society, told MailOnline.

‘As with any meteor shower, it’s best to escape the lights of the city and head to a dark site.’

However, Dr Massey also pointed out that the International Meteor Organisation is not flagging Friday’s shower, and that it may be ‘better for dedicated amateur astronomers than the wider public’.

The Draconid Meteor Shower, sometimes referred to as the Giacobinids, is one of two meteor showers that grace the skies in October every year.

The other is the Orionids, which are set to peak in the sky on the night of October 21, between midnight and dawn.

Explained: The difference between an asteroid, meteorite and other space rocks

An asteroid is a large chunk of rock left over from collisions or the early solar system. Most are located between Mars and Jupiter in the Main Belt.

A comet is a rock covered in ice, methane and other compounds. Their orbits take them much further out of the solar system.

A meteor is what astronomers call a flash of light in the atmosphere when debris burns up.

This debris itself is known as a meteoroid. Most are so small they are vapourised in the atmosphere.

If any of this meteoroid makes it to Earth, it is called a meteorite.

Meteors, meteoroids and meteorites normally originate from asteroids and comets.

For example, if Earth passes through the tail of a comet, much of the debris burns up in the atmosphere, forming a meteor shower.

Source: Read Full Article