Even ancient sloths liked meat and two veg! Giant 10ft-long creature that lived in South America 1.8 million years ago was an omnivore, unlike its strictly plant-eating relatives, study finds

- Sloth that lived around 1.8 million years ago was not strict vegetarian, study finds

- The 10ft-long Mylodon darwinii, known as ‘Darwin’s ground sloth’, likely ate meat

- It had been thought it was a herbivore because most living sloths only eat plants

- But chemical analysis of amino acids in preserved sloth hair revealed differently

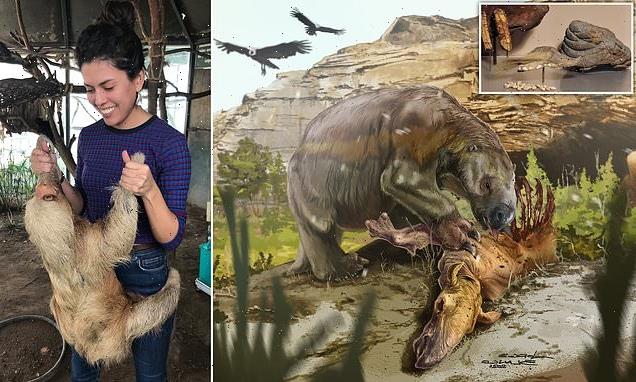

An extinct ground sloth that lived in South America up to 1.8 million years ago was not a strict vegetarian like most of its living relatives because it likely ate meat, a study has found.

Researchers said the gigantic 10ft-long creature was an omnivore that at times consumed meat as well as plants.

It had long been thought that Mylodon darwinii, also known as ‘Darwin’s ground sloth’, was a herbivore because the majority of living sloths only eat leaves, fruit and twigs, although some occasionally snack on an insect or bird eggs.

However, chemical analysis of amino acids preserved in the ancient sloth’s hair revealed evidence of animal protein, suggesting they may have been scavengers.

‘Whether they were sporadic scavengers or opportunistic consumers of animal protein can’t be determined from our research, but we now have strong evidence contradicting the long-standing presumption that all sloths were obligate herbivores,’ said lead author Julia Tejada, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History.

Meat eater: An extinct sloth that lived in South America up to 1.8 million years ago was not a strict vegetarian like most of its living relatives because it likely ate meat, a study has found

WHAT WAS THE GIANT ‘DARWIN’S GROUND SLOTH’?

The first specimen of Mylodon darwinii was found by Charles Darwin in 1832

The first specimen of the ancient ground sloth Mylodon darwinii was found by Charles Darwin in 1832.

He identified it as belonging to the same family as modern sloths, but British anatomist and paleontologist Sir Richard Owen later described it as a new species, and named it in honour of its discoverer.

Mylodon, or ‘Darwin’s ground sloth’, lived throughout South America — from Bolivia in the north to southern Patagonia — between 1.8 million years and 12,000 years ago.

Unlike some of its relatives, it did not burrow or climb trees, and it also wasn’t a vegetarian, according to this new research by the American Museum of Natural History.

It is not known what caused its extinction, although climate change has been suggested as one possible reason.

The six living sloth species are all relatively small, plant-eating tree-dwellers that live in the tropical forests of Central and South America.

However, hundreds of their extinct cousins, some of which were as large as an elephant, roamed ancient landscapes from Alaska to the southern tip of South America.

One of these species, known as Mylodon darwinii, is thought to have weighed between 2,200 and 4,400lbs and was nearly 10ft long. It lived during the Pleistocene epoch, between 1.8 million years and 12,000 years ago.

Based on previous research that looked at dental characteristics, jaw biomechanics and preserved excrement from recent fossil species, as well as the fact that most modern sloths only eat plants, it had been thought that Mylodon darwinii was a vegetarian.

But these methods could not reveal with certainty whether an animal might have ingested food that requires little or no preparation and is completely digested, as happens in carcass scavenging or some other kinds of meat-eating.

For that reason, this study used an innovative approach involving nitrogen isotopes locked into specific amino acids — biological compounds that are the building blocks of proteins — within animal body parts, known as ‘amino acid compound-specific isotope analysis.’

These nitrogen isotopes are found in food consumed by an animal and are preserved in its body tissues, including hair, fingernails, teeth or bones.

By first analysing the amino-acid nitrogen values in a wide range of modern herbivores and omnivores to identify what eating plant, animals or a mixture would look like, fossils can then be measured to determine the food they consumed.

This offers paleontologists a unique window into the diets of animals, allowing them to determine their ‘trophic level’ — whether they were plant-eating herbivores, mixed-feeding omnivores, meat-eating carnivores, or specialised marine animal consumers.

‘Prior methods relied solely on bulk analyses of nitrogen and complex formulas that have many untested or weakly supported assumptions,’ said study co-author John Flynn, from the American Museum of Natural History’s division of paleontology.

‘Our analytical approach and results show that many previous conclusions about tropic levels are poorly supported at best, or clearly wrong and misleading at worst.’

Researchers used samples from seven living and extinct species of sloths and anteaters — which are closely related to sloths — as well as from a wide range of modern omnivores.

While the other extinct sloth in the study, the North American ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis, was determined to be an exclusive herbivore, the data clearly flagged Mylodon as an omnivore.

‘We now have strong evidence contradicting the long-standing presumption that all sloths were obligate herbivores,’ said lead author of the research Julia Tejada (pictured)

Previous research has suggested that there were more herbivores than could be supported by the available plants in the ancient ecosystems of South America, indicating that some of those herbivores may have been finding other sources of food.

Evidence from this new study would appear to support that theory.

‘These results, providing the first direct evidence of omnivory in an ancient sloth species, demands reevaluation of the entire ecological structure of ancient mammalian communities in South America, as sloths represented a major component of these ecosystems across the past 34 million years,’ said Tejada.

The study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source: Read Full Article