Diana Ossana is flat on her back, wracked with grief. She’s just lost her best friend and writing partner, Larry McMurtry, a man she nursed through open heart surgery in 1991 and a couple of other heart attacks, who after three years of battling congestive heart failure, finally succumbed Thursday in his home in Archer City, Texas. He was 84. “Larry through stubbornness and brilliance kept going,” said Ossana. “He kept going. I feel like one of my limbs is cut off. We’re all pretty crushed.”

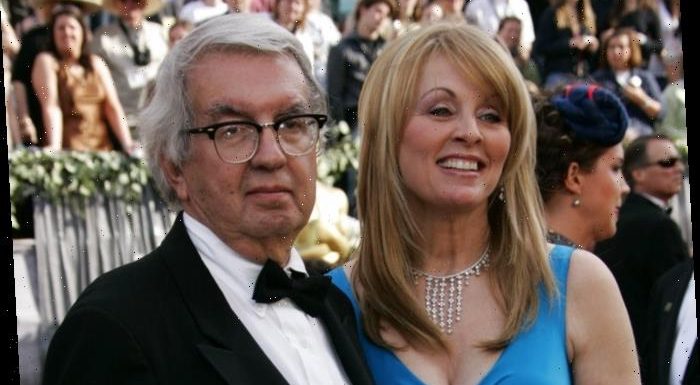

Ossana picked up the phone to talk about her writing partner of 28 years, with whom she shared the 2006 Screenplay Oscar for adapting Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain.” “We were each other’s best friend,” she said. “Larry would tell people to call me in the last 10 years or so: ‘Ask Diana, she knows me better than I do myself.’ From the beginning of our friendship, it felt symbiotic, maybe the way twins feel. I’m not a twin. But we would finish each other’s sentences.”

The screenwriter is a member of a large sorority of women friends Texas-born McMurtry nurtured over the decades, from journalist Maureen Orth to the late production and costume designer Polly Platt, whom he got to know during the development and production of her husband Peter Bogdanovich’s “The Last Picture Show” (1971), the second Oscar-winning movie adapted from one of McMurtry’s novels. (McMurtry talked to Karina Longworth for her well-reported “You Must Remember This” podcast on Platt.)

Ellen Burstyn in “The Last Picture Show”

Columbia Pictures

Did he harbor romantic feelings for Ossana? “I don’t know, he may have felt that way about me,” she said. “The reason it lasted was that it didn’t turn into that. He used to talk to me about all the women. At one point, I asked, ‘Do they know about each other, all these women?’ His eyes got big. ‘No, oh no.’ He’d get on the phone and talk to five, six, seven ones before bed. It was not a lot conversation, mostly listening. He was fascinated with women. He thought they were one of the great mysteries of the universe. He had no interest in men. He said, ‘If you want to learn about emotion, you have to go to women.’”

When he was writing his early novels, such as 1961’s “Horseman, Pass By” (which became the Oscar-winning Martin Ritt western “Hud,” starring Paul Newman) and 1963’s “Leaving Cheyenne” (which became his least successful movie, Sidney Lumet’s “Lovin’ Molly”), McMurtry married and divorced fellow academic Jo Scott, raised their son, musician James McMurtry, and never married again until 2011, when he impulsively wed his old crush, Faye Kesey, the widow of his old Stanford friend and literary rival, Ken Kesey. The couple moved in with Ossana.

“I think Larry just decided he wanted to have a companion,” said Ossana. “We used to go up there and visit them in Oregon. He gave her a call, she showed up for a few days, and he decided he wanted to get married. We are all like, ‘What? Really?’ They were elderly. The way I explained it to people was, ‘They don’t have much time for a two-year engagement. They want to get on with what’s left with their lives.’ Faye was quite devoted to Larry.”

“Terms of Endearment”

Paramount Pictures

Back in 1991, Ossana pulled the usually prolific novelist — who published in his lifetime 29 novels, including 1985’s Pulitzer Prize–winning “Lonesome Dove” (which yielded the beloved Emmy and Peabody-winning 1989 western miniseries starring Robert Duvall, Tommy Lee Jones, and Diane Lane), three memoirs, two collections of essays, and more than 30 screenplays — out of a depression that left him lying on her sofa in Tucson for a year. “He had open heart surgery,” she said. “I thought he’d recovered physically wonderfully after six weeks, but then darkness descended over him. He couldn’t seem to find the light.”

But he kept on typing out “Streets of Laredo” on his Hermes at Ossana’s Tucson kitchen counter, his darkest, saddest western novel. Simon and Schuster wanted the manuscript delivered on discs, so Ossana entered his pages onto her computer. “As I was doing it we would talk about it a lot,” she said. “That’s what happened. He came to trust me and my judgement.” McMurtry never transitioned to writing on a computer. ‘We tried about 10 years ago,” she said. “He could not cotton to it, couldn’t stand the touch of the keyboard.”

But when the novel was done, McMurtry “stopped reading, writing, he was just staring at the mountains,” she said. “He was someone who read five newspapers a day, and God knows how many books a week. Months, over a year passed.” To pull him out of his slough of despond, she pitched him a story about Depression outlaw “Pretty Boy Floyd.”

“He kept getting offers to write scripts and batting them away,” she said. “He was fascinated with the difference between mythology and reality. There was a lot of that within the Pretty Boy Floyd story. He humored me at first, but about halfway through I could see something sparking in his eyes. Sure enough, he said: ‘I’ll write it, but only if you write it with me.’”

That’s how Ossana jumpstarted McMurtry back to life. Writing together “was very easy, because Larry and I finished each other’s sentences, our feelings, and our thoughts,” she said. “That’s not to say we didn’t argue plenty. But he was never mean-spirited or threatening.”

Together they wrote two novels, “Pretty Boy Floyd” and “Zeke and Ned,” and countless screenplays and teleplays. They adapted his “Lonesome Dove” continuations “Streets of Laredo” (1995), “Dead Man’s Walk (1996), and “Comanche Moon” (2008) as miniseries. And memorably, Ossana talked McMurtry into co-writing a script from Annie Proulx’s novella “Brokeback Mountain.” The writers convinced the reluctant Proulx to let them adapt her heartbreaking western gay romance, which after many false starts eventually got made with Ang Lee directing Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger. The film was a hit and won three Oscars in 2006, including Adapted Screenplay, notoriously losing the Best Picture Oscar to “Crash.”

“Brokeback Mountain”

Focus Features

The secret to McMurtry’s extraordinary success was his characters. His books and movie adaptations were not plot-driven. “Terms of Endearment,” which writer and rookie director James L. Brooks adapted for the screen, worked as well as it did (winning five Oscars) because audiences were drawn to imperious Houston widow Aurora Greenaway (Shirley MacLaine) and her fierce devotion to her less glam, down-to-earth daughter Emma (Debra Winger), and her delicious flirtation with ex-astronaut Garrett Breedlove (Jack Nicholson). (“I love you too, kid.”) “‘Lonesome Dove’ was embraced because the characters were so powerful,” said Ossana. “They overcome the myth. He wrote the most realistic compelling characters, good and bad, that actors want to play, and people want to love.”

Sitting here thinking of the greatness of Larry McMurtry.

Among the best writers ever. I remember when he sent me on my way to adapt “Terms” – his refusal to let me hold him in awe. And the fact that he was personally working the cash register of his rare book store as he did so.

— james l. brooks (@canyonjim) March 26, 2021

McMurtry leaves behind Booked Up, his one surviving Archer City bookstore, which will be taken over by its manager Khristal Collins, as well as a personal library crammed with 30,000 more volumes. It will take some time to figure out what to do with several unpublished novels and shorter writings, which include “62 Women,” a memoir about McMurtry’s relationships over the years, and “A Night at the White House,” about a Reagan state dinner McMurtry attended with Prince Charles, Princess Diana, and John Travolta.

“Joe Bell”

Courtesy of TIFF

Most recently Ossana and McMurtry collaborated on the script for Toronto 2020 debut “Joe Bell” (2021, Solstice Studios), starring Mark Wahlberg, which was originally developed as a project in 2015 for director Cary Fukunaga, who moved on to make James Bond movie “No Time to Die.” It’s based on the true story of a working class father of a gay son who crusades against bullying by taking a walking trek across the country. “That script languished, like scripts do,” Ossana said. “It was picked up by producers who found Ray Green to direct it.”

There are piles of unproduced screenplays. “Lots of scripts didn’t get made,” said Ossana. “They’re on shelves all over place.”

Source: Read Full Article