CHRISTOPHER STEVENS: Shamelessly naughty, shockingly liberated, defiantly outspoken… Fay Weldon’s life, like her novels, was full of drama

My husband and I met in bed, wrote novelist Fay Weldon, the mistress of the zinging one-liner.

She meant what she said: they had sex as strangers at a party and fell in love the next morning.

That confession was typical of her — shamelessly naughty, shockingly liberated, defiantly outspoken.

Fay Weldon, who has died aged 91, couldn’t open her mouth without provoking outrage.

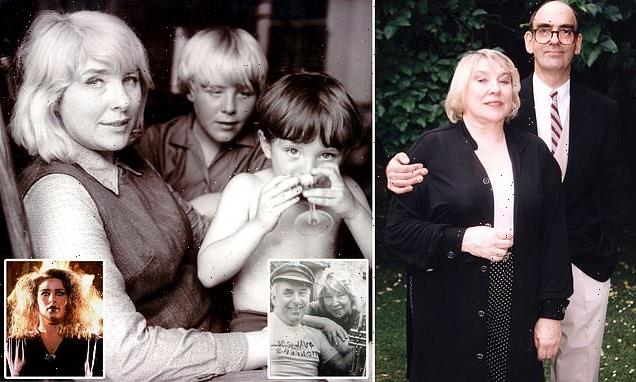

Fay and Ron Weldon had three sons —Dan, Tom and Sam — and Fay was stepmother to Ron’s teenage daughter, Karen

Fay Weldon was born Franklin Birkinshaw in 1931, in Alvechurch, Worcestershire, into a thoroughly unconventional family

‘Selling your body is not any big deal,’ she announced 20 years ago, after revealing in her autobiography that she worked as a nightclub hostess during her first marriage in the 1950s.

‘Rape is nasty — death is worse,’ she told a speechless James Naughtie on Radio 4’s Today programme in 1998. ‘If you are alive and unmarked then there are worse things that can happen to you.’

Feminists didn’t know what to make of her. She refused to condemn the male sex, but any man who crossed her was made to regret it bitterly.

‘I am probably the one, the only feminist there is,’ she said cheerfully, ‘and the others usually come round to my way of thinking in the end.’

Her life, like her books, was crammed with astonishing sexual adventures, betrayals, scandals, catastrophes and miraculous strokes of luck.

She relished it all with an enthusiasm that left the buttoned-up British establishment reeling.

Her best-seller The Lives And Loves Of A She-Devil, about the vengeance of a woman scorned, was adapted for a 1986 BBC1 serial that hit TV screens like the first cannonball of a revolution.

Julie T Wallace starred as Ruth, a wife whose husband dumps her for a more glamorous mistress.

Instead of accepting her humiliation, Ruth plots a merciless revenge. The drama, co-starring Dennis Waterman and Patricia Hodge, divided the country with its uncompromising message: Men, beware!

Fay Weldon was born Franklin Birkinshaw in 1931, in Alvechurch, Worcestershire, into a thoroughly unconventional family.

Her grandfather, the prolific novelist Edgar Jepson (author of lurid tales with titles such as The Cuirass Of Diamonds), was a devotee of spiritualism and astrology — a fascination he passed on to his granddaughter.

He was also a keen advocate of free love, and at 69 made his young mistress pregnant. Fay’s parents, Margaret and Frank, escaped the family scandal to New Zealand, where their own marriage disintegrated.

After school in Christchurch, Fay was sent to South Hampstead High School in London to complete her education.

When her father died, she was 17, about to start university and hadn’t seen him for three years.

Julie T Wallace starred as Ruth, a wife whose husband dumps her for a more glamorous mistress

In 1994, she married the poet Nick Fox. He became her business manager and they seemed happy at first

On the night train to St Andrew’s University, she threw away her black armband.

‘I remember the act of will this required,’ she wrote, ‘but I had decided that I was going to be a person without a past, only a future.’

By 22, she was pregnant, by a penniless folk singer at the Mandrake Club in Soho.

‘In 1953,’ she wrote, ‘in the eyes of the world, I was stigmatised as a Bad Girl. There were no state benefits available for the likes of me.’

An abortion was not only illegal but, at £200 (equivalent to £4,400 today), too expensive.

Fay stood on the Albert Bridge, looking down into the Thames and then at the sunset. She had no right, she decided, to end her unborn child’s life, if that meant it would never see a sunset over London.

She struggled to survive, working first as a street market researcher. Threatened with eviction, and with it the prospect of having her baby Nicholas taken into care, she agreed to marry a man twice her age.

His name was Ronald Bateman: the headmaster of a technical college, he was recently divorced. Fay didn’t love him —years later, she accused herself of being ‘a heartless, practical, scheming monster’.

But Bateman had his own schemes. She soon realised that he needed a wife and child to seem respectable. A divorced head teacher was unlikely to keep his job.

He was also a reckless sadist who enjoyed terrifying his young wife by speeding on narrow roads, overtaking and swerving to make her scream. This was an era before compulsory seatbelts, and Fay often had her toddler on her lap.

Bateman was an inveterate voyeur. He didn’t want to have sex with Fay, but he was eager for her to take lovers.

Ron Weldon, an artist, was married to the painter Cynthia Pell but they had separated and, within a couple of years, he and Fay were married

When she refused to sleep with his friends, he found work for her as a hostess in a seedy Soho wine bar.

She described it as, ‘flirting and dancing, dangling of the legs from bar stools, the semi-baring of the bosom. I would leave the house in the evenings dressed up to the nines, low-cut dress, very high heels, net stockings and tightly belted waist. Good girls in those days dressed so as not to be noticed. Bad girls drew attention to their assets.’

Her husband also encouraged her to sleep with a market trader who made it plain he fancied her.

The man took her back to his home, turned the radio up loud and subjected her to a painful sexual assault.

‘Well, what did I expect?’ she chided herself. ‘I could scarcely cry rape, since I had freely put myself in this situation.’

The man’s parting shot was that she ought to count herself lucky. He didn’t usually fancy fat women, he said. In sheer self-loathing, she lost two stone.

Fay then resolved to have sex with the men she chose, not ones picked out by her husband.

A friend she called ‘Ellen’ was working for an advertising agency, wining and dining clients.

Fay joined her, ‘sometimes for foursomes in her flat, or in lay-bys outside London. The fear of discovery added to the danger — and danger added to the experience.’

Instead of being a sordid dead-end, her work ‘entertaining clients’ led to two careers.

One was as a writer: at home, she would lock herself in the bathroom to write a debut television play.

The first script was rejected as too explicit — no one, explained a man at the BBC, wanted to watch a drama about prostitutes, ‘no matter how well written’. She took heart from that scrap of praise.

Her second opportunity was in advertising. Ellen helped her land work as a copywriter for advertising giant Ogilvy & Mather.

Her early efforts were not well received: the client rejected ‘Vodka gets you drunk faster.’

But a commission from the Egg Marketing Board led to a catchphrase that went down in history: ‘Go to work on an egg.’

Cartoonists loved it — one advert featured a workman with a pickaxe over his shoulder, trundling along on an egg.

Comedian Tony Hancock did a series of TV ads with Fay’s phrase as the punchline. At first, she modestly claimed it had been a team effort.

In later life, she shrugged and took the credit. ‘Unzip a banana’ was another of her clever taglines, with its hint of a saucy double meaning.

Her career flying, at a party in 1961 she fell into bed with that man who introduced himself next morning.

Ron Weldon, an artist, was married to the painter Cynthia Pell but they had separated and, within a couple of years, he and Fay were married.

Weldon has plundered her own extraordinary life for inspiration for her 40-plus best-selling novels — the most celebrated of which, The Life And Loves Of A She-Devil, she wrote aged 53

By the end of the 1960s, her first novel was published. Its title, The Fat Woman’s Joke, carried echoes of that hate-filled jibe by the market trader who raped her

For the next decade, she said, they were rarely out of bed — sex was the whole basis of their relationship.

‘I thought the only way to know a man properly was to know what he was like in bed,’ she said, ‘and my appetite for knowledge was formidable.’

After the wedding, Ron gave up art and opened an antiques shop in Primrose Hill. Fay bragged that their customers included David Bailey, Jonathan Miller and Alan Bennett.

They had three sons —Dan, Tom and Sam — and Fay was stepmother to Ron’s teenage daughter, Karen. But after his divorce, Ron’s relationship with Cynthia became acrimonious.

Vicious three-way rows erupted. Cynthia once picked up baby Dan from his cot and threw him across the room, onto a sofa.

‘You have stopped Ron painting,’ Cynthia accused Fay. ‘What has he done, marrying a woman like you? An office worker!’

Fay suspected that Ron sometimes mollified his former wife by sleeping with her. ‘In the 1960s,’ she said, ‘we women were in competition. We had little sense of sisterhood.’

After a breakdown, Cynthia spent 15 years in a mental institution and eventually took her own life.

Ron was an advocate for psychiatric therapy and insisted as a condition of marriage that Fay went into analysis. If she didn’t understand the theories, he said, she would never understand him.

Fay understood him all too well. When she had to cut short a family camping holiday in 1969, to attend the funeral of her sister Jane (who had died aged 39 from cancer), Ron didn’t go with her.

‘Like so many men of his generation,’ she remarked, ‘Ron found death embarrassing.’

But she also knew he had struck up a relationship with the woman in the next-door tent on the campsite — her marriage had broken down, and Ron was ‘consoling’ her.

For eight years, Fay went through the motions of therapy, visiting a woman called Miss Rowlands in Bloomsbury, ‘to lie upon her couch, confess my boring sins and keep hidden the true ones, hating every minute of it’.

When she pleaded to end the sessions, Miss Rowlands warned her that she’d regret the decision — implying that the Weldon marriage would fall apart without constant analysis.

For the rest of her life, Fay maintained a seething dislike for all therapists.

By the end of the 1960s, her first novel was published. Its title, The Fat Woman’s Joke, carried echoes of that hate-filled jibe by the market trader who raped her.

Her reputation soared and she was commissioned to write the first episode of a major TV costume drama series, Upstairs Downstairs.

Though the pretence in the Weldon house was that the antiques business was their bread-and-butter, Fay earned far more than her husband.

‘What drove me to feminism 50 years ago was the myth that men were the breadwinners and women kept house and looked pretty,’ she said. ‘That myth finally exploded and I helped to explode it.’

Anyone reading her novels — she wrote 31 in all — or watching the TV adaptations during the 1970s and 1980s could guess that her marriage was in a bad way.

Last July, aged 91, after moving into a care home, she and Nick were divorced. She alleged ‘financial coercion and mismanagement’

Ron finally left her for his astrological therapist. The day before their divorce was set to be finalised, he died from a heart attack.

In 1994, she married the poet Nick Fox. He became her business manager and they seemed happy at first.

He supported her when her son Tom was sent to a Dutch prison for three years on drug smuggling charges.

She had always defended Tom’s bohemian lifestyle as a professional fire-eater and traveller with hippy communes, but friends said his arrest in Amsterdam, in possession of 15,000 Ecstasy tablets, tore her apart.

Once a heroine to them, the literary Left never forgave her for turning on Labour’s women MPs in 1999.

‘En masse,’ she accused them, ‘you fell in love with Tony Blair.’ She despised Blair, declaring that politicians like him ‘spend too much time honing their public personas — they’re like girls dressing up to impress the boys’.

The near 30-year marriage to Fox ended badly. In 2019 she wrote an article about their ‘happy’ marriage, but in an interview with this paper in 2020, she revealed that she’d attempted suicide the next day.

Last July, aged 91, after moving into a care home, she and Nick were divorced. She denounced him as ‘controlling’ and ‘coercive’ and said she was glad to have escaped from him.

Fox said he was ‘stunned, bewildered and sad’ by her claims.

However overwrought her private life, she was always fearlessly independent as a writer.

Despite being shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1979 for Praxis (a novel about a suburban housewife turned prostitute), she rarely won awards.

She knew why, she said: her sentences were too short and her books were too readable. She’d been a judge on enough literary panels, she added, to know that the most boring book always won.

In 2001, she took her revenge on the pretentious world of literature by writing a romantic novel to order, The Bulgari Connection, for the international jewellery brand.

‘I thought, oh no, dear me, I am a literary author, my name will be mud forever. But after a while, I thought, I don’t care. Let it be mud. They never give me the Booker Prize anyway.’

Fay Weldon always was a she-devil.

Source: Read Full Article